Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.

Introduction

About 30 years ago I met with my then-business partner to think into the future and try to anticipate what we might see in terms of changes in the healthcare system. The results of this challenging process were:

- An accepted ability to measure the risk of a specific population to help quantify the needed healthcare resources for that population

- An accepted ability to conveniently quantify the level of benefits, perhaps a benefit index tool

- Strong likelihood to move from a defined benefits health care model to a defined contribution model

- A shift away from an intense provider contracting to an all-payer model.

Thirty years later we see:

- Multiple risk assessment models and tools, some government-promoted (i.e., HCCs for ACA and Medicare Advantage) and some private vendor models (i.e., 3Ms CRGs, DxCGs, ETGs, PRGs, etc.)

- Actuarial Value calculators, some government-developed (Federal AV Calculator) and many private vendor approaches

- Considerable discussion in the market offering defined contribution approaches (i.e., FSAs, employer participation using vouchers in ACA marketplace, etc.)

- Potential progress towards this based upon health plan transparency files and contracting information

Little did I know then that the Federal government would be the catalyst to encourage these changes. Early work I was involved with in the State of Washington and their Basic Health Plan approach demonstrated the significant need for a valid risk adjustor. Our initial primitive discussions talked about “experience claiming” or an approach to transfer funds from the carriers getting the most favorable patients to those carriers getting high-cost high-risk patients. These discussions envisioned an approach where a centralized agency would have the authority to assess the risk and be sure that selection bias was eliminated from the process.

It was clear to us that a consistent way to quantify benefits was required to help the population understand a “true” and valid understanding of what benefits were worth. Too many individuals misinterpret the value of a benefit without a good “actuarial” understanding of what benefits are worth. The emergence of benefit indices and actuarial value calculators provided this much needed capability. In addition, ACA defined metallic levels to further standardize benefit categories benefitting the general public.

The transition in retirement benefits from a defined benefit model to a defined contribution model worked well. It was obvious to us that a natural transition for health benefits might follow that path. It has been slow going, but most recently the discussion for this transition has intensified and regulations are starting to enable the transition. Three out of the four are in obvious development. But what is the status of the last topic? Time will tell, but it seems that momentum is building in this area also.

Health Plan Transparency Files

CMS has mandated the development of both provider and health plan transparency files, including a transition over the next few years, to provide varying levels of information to the public about contractual payments with providers. These files are substantial, many times exceeding the capacity of most software tools. A recent project involved files a billion records in length with more than five terabytes of key useful information. Traditional tools fail us in such situations. Fortunately, we were able to utilize sophisticated cloud-based services enabling us to fire up significant processing power and sophisticated programming resources resulting in an efficient process to understand the information in these files.

This information will enable the user to know what a specific health plan paid a specific provider (by NPI code) for a specific service. There is no more mystery, it will be known to those who spend the time and effort to build the tools to use this information. Where Plan A pays more, they will negotiate for less when a lesser payment is observed for Plan B. Eventually, as plans pursue this enhanced negotiation process, payment rates will likely stabilize around common values in a given market. This will naturally result in a common payment level for all health plans and specific providers. This is one step away from a common price for common services.

Transition to All-Payer

Once payers have settled in on nearly common prices for services to specific providers, the next question begging for an answer is “why can’t the same price be appropriate and/or reasonable for all patients?”. The essential market agreement as to what is a reasonable price to pay for services provided to members of a health plan opens up the door to an all-payer system. Why do we pay different amounts for different types of members? Since the government is the primary sponsor of these lesser payments, why does the private sector subsidize the government payer? Why isn’t the same price fair for all? Transparency will open up the door to this question, but the government will likely be the entity asked to answer the question.

Medicare has set its payment levels as a proxy for a reasonable payment. The acceptance of this amount as a placeholder for a reasonable payment level provides some progress toward an all-payer system.

Recent analysis of typical health plan private sector reimbursement shows that health plans often pay providers at or above 150% of Medicare. Some high-performance networks pay providers 125% of Medicare, and possibly more through incentive programs.

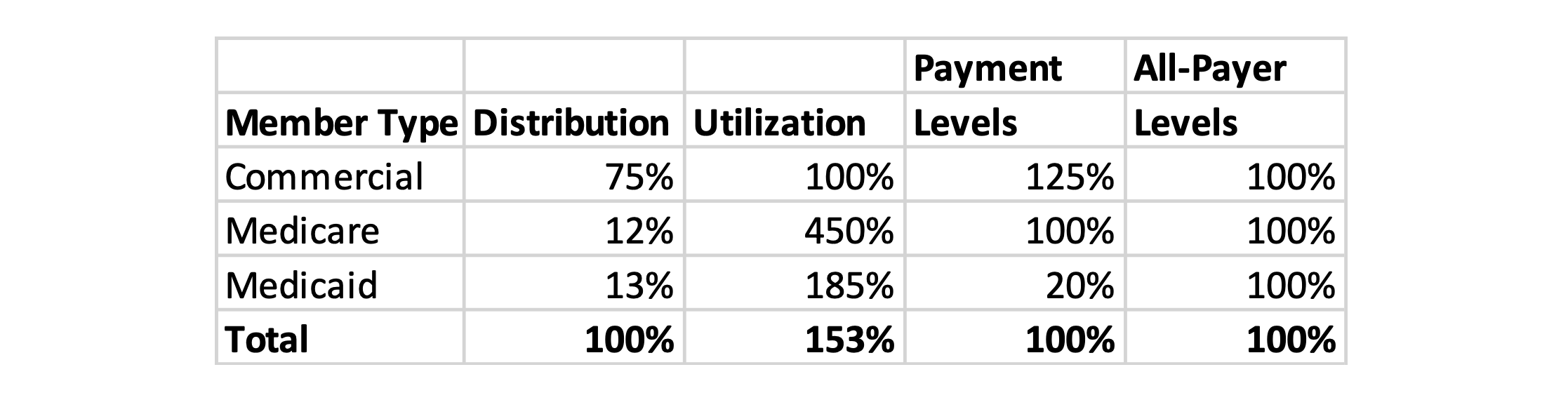

Although it varies by state, Medicaid reimbursement levels are substantially less than Medicare. Table 1 shows an approximate calculation of the impact of overall provider payments set at Medicare levels in a high-performance environment where Medicaid payment is substantially less than Medicare.

Table 1: All-Payer Scenario A

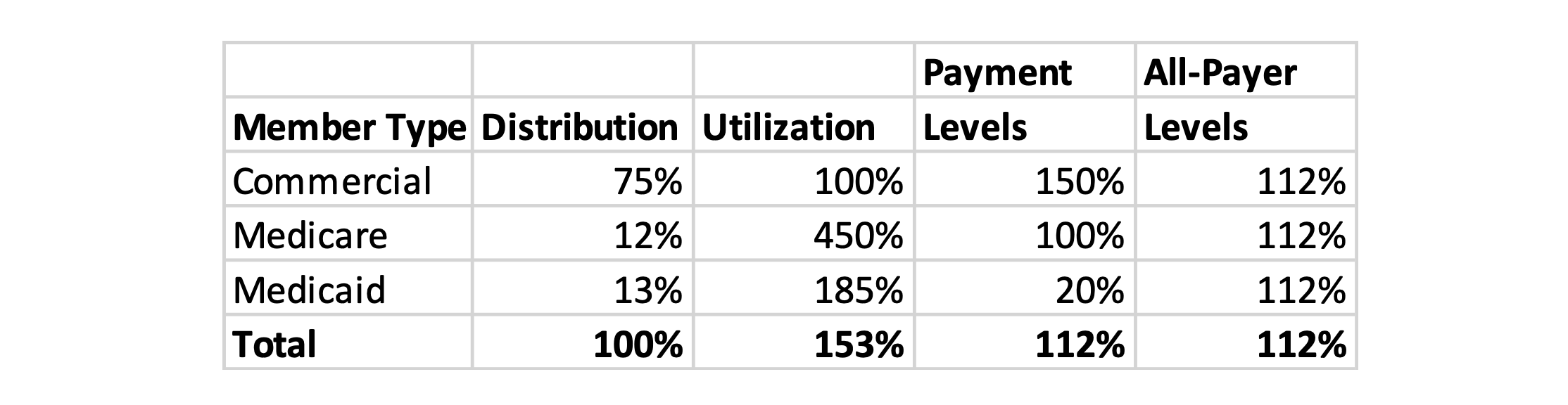

Table 2 shows a scenario where commercial pays at a higher level more typical of today’s competitive payment levels. This scenario suggests a payment level higher than Medicare (i.e., 112%) would be required to compensate providers at a comparable rate to current levels.

Table 2: All-Payer Scenario B

Summary

It is exciting to anticipate the impact on the market of this new transparency information and the enhanced negotiations that will emerge. But will this lead the market into even greater enhancements or just a continuation of the current approach? I for one am anxious to see the market mature, reduce redundant overhead costs, and transition to what truly is the most important factor, the elimination of potentially avoidable care or care management enhancement.