Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.

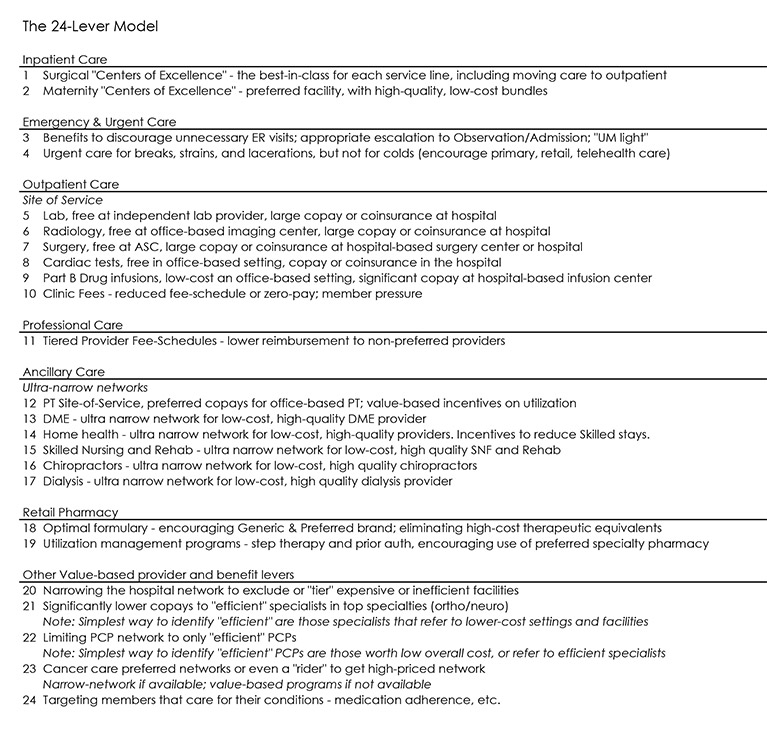

This issue of Inspire is the first in a series of Inspire issues devoted to the 24-lever model.

Introduction

It is a story the health plan actuary knows all too well: The marketing and sales team creates a new commercial product, sends it off to the actuaries for pricing, and when pricing arrives, are not very happy to see only minimal savings predicted. And they ask, what happened? Some likely suspects are:

- Lack of network differentiation. The provider network may have changed, but the underlying cost structure has not improved to a significant degree.

- Lack of cost-saving benefit incentives. The differentiators are missing that are needed to help the member “do the right thing” from the standpoint of overall costs.

- Lack of utilization management controls. The product design allows too much leeway for members and providers to make decisions on their own, and does not encourage members to see physicians that manage the cost of care.

Having had this happen, I prepared a checklist for sales to select various product features to achieve savings. The result of this exercise became the “the 24-lever model.”

Over time, the model grew to take a key role in the strategic planning for an early Integrated Delivery and Financing System (IDFS). The common-sense levers that made one product more affordable also created the blueprint for creating the low-cost product they were designing for the future.

The Problem: Health Care Premiums

This article will help health system professionals understand practical benefit design changes that lower the cost of health care and in turn lower health care premiums, and is intended for audiences such as:

- Large employer groups, who can learn how today’s incentives are oftentimes stacked against them.

- Commercial health plan actuaries and executives interested in creating low or lower cost products.

- Provider-owned health plans interested in understanding what levers may be needed to achieve the low-cost structure of a closed-network IDFS.

The Issue: Misaligned Incentives

The 24-lever model works like this: If every health plan consumer made the right choice at every possible care decision point and there was a product effectively able to capture this behavior, the health plan or employer group customer should realize significant savings of up to 20% or even 25%.

Here are the ways today’s health care system works against the health care consumer:

|

The Right Decision |

Working Against the Health Care Consumer |

|

Consumers pay as little as possible for appropriate, high-quality care. |

Very little or very hard to find price transparency on which facility or setting provides the lowest-cost care. |

| Consumers select the best physician for their specific health care needs. | Very little quality and outcome data to show whether one facility or physician is worth a premium price. |

| Consumers have a procedure or take a prescription only when necessary. | Even less available data to tell the consumer which providers perform in an efficient, low-cost manner, and which drugs are the best value. |

A Solution: The 24-Lever Model

We can assess realigning some of these incentives through various benefit and network strategies. The levers are outlined in the exhibit on the next page, and described here.

Inpatient Surgical and Maternity Care – “Centers of Excellence”

Because surgeries and deliveries are often planned, they can follow the economics of supply and demand. The “Centers of Excellence” strategy focuses on identifying the most efficient, low-cost networks, with great outcomes, and strongly encouraging them in the benefit. As an example, I have seen the cost of hip replacements performed in the outpatient setting at levels close to one-third of those in the inpatient setting.

Emergency Care – From Urgent Care to Admission

Unlike surgical care, emergencies are not planned. Often the consumer is in a position where they are not necessarily thinking about the cost of care, and make a decision that is bad for both their pocketbook and their insurer. The benefit and network design needs to help these consumers make the right decision, from encouraging telehealth or physicians with weekend hours to finding an urgent care center (but not for a cold please!). And if the ER is needed, finding a hospital that will treat efficiently, with no unnecessary escalation to observation or even a medical admission, can save both the consumer a lot of money, and lead to a better patient experience.

Outpatient Care – The Site-of-Service Dilemma

Think about your experience with a basic lab test. You may have visited an independent lab in a strip mall, or perhaps a local community hospital. You may not be aware that the same test in these two settings could have a difference in cost of as much as 10 times, and typically at least 3 times. A simple benefit change of charging no copay for the independent lab can lead to significant cost savings. Or perhaps better, the hospital could “right price” shoppable services like this to match the lowest cost settings so that consumers do not get stuck in the middle of this cat-and-mouse game between providers and insurers

Many other outpatient services follow a similar pattern, including radiology, surgery, cardiac, drug infusions, and even physician visits. Today it is possible to go to a physician, perhaps one 30-miles away from the hospital, and receive two bills (one from your physician and one from the hospital – called a clinic fee) for your visit. It happens for some hospital systems, is currently legal, but obviously not a positive experience for either the consumer or the health plan trying to keep costs low.

Professional and Ancillary Care – Encouraging Efficient Care

The professional and ancillary levers reference the savings achieved from narrowing a network of providers, where the benefit either significantly incentivizes the member to use the preferred, most efficient network, or makes the non-preferred provider out-of-network. It is important to stress that the preferred network is truly preferred —meaning, providers of equal or higher quality, along with lower cost. These are the providers that understand care management, and how to provide the least amount of care while still achieving the best outcomes. These providers are often lower-cost because they are referring to the appropriate setting or facility for their specialty care.

Retail Pharmacy – Optimal Formulary and Program Design

There are many programs to reduce pharmacy costs through effective product design. The list below provides an inventory to consider:

- Effective clinical programs, concurrent drug utilization review, prior authorization;

- Step therapy, quantity limits, retail to mail, generic use, coverage of OTC;

- Specialty drug mgmt., site of care optimization, drug adherence, formularies.

Value-Based Provider and Benefit Levers

With the recent focus on health care costs because of health care reform, value-based provider reimbursement and benefit designs are often mentioned as the bipartisan answer to all our health care cost problems. By just quoting, “we will pay for outcomes and not the volume of services” makes everyone nod in agreement. But to an actuary setting a price on a product, we will want to see proof of savings. The measurement of which physicians and provider networks are efficient and low-cost is complicated and perhaps controversial (“my patients are sicker”), but I have seen it effectively accomplished. Ultimately, the primary care physician performing important preventive care, referring to the most efficient and effective specialists only when necessary, is how the savings of 20-25% is achieved.

Conclusion

This is the first Inspire in a series of 24-lever-focused articles which look at lowering the insurance premiums through implementing optimal benefit and network levers. These levers lower the underlying cost of care within the product primarily through encouraging consumers to make the right decisions.

Ultimately, the model describes how to create the optimal benefits wrapped around a highly efficient provider network. Such a product design is necessary to keep future premiums affordable. We see many of the incentives in the health care system today are misaligned, encouraging inefficient and costly care. Ultimately, health plans, IDFSs, employers, and even individuals can have a significant impact on the overall cost of care if they follow the steps and ideas in this model.

About the Author