Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.

Introduction

One of the primary responsibilities of health plans, like Aetna, Cigna and UnitedHealth Group, is to remain financially viable in order to meet its financial and legal obligations to members, plan sponsors, providers and employees. In many cases the reason a health plan suffers financial losses is that the premium rates charged for its insured business are simply too low.

This may happen if the actuary underestimated costs during the rate-making process, but it may also happen if management made a business decision to lower rates in an attempt to sell more business. Of course, there is also a possibility that state regulators will deny a requested rate increase.

In addition to its financial and legal obligations, a health plan has a moral obligation to make sure that members have reasonable access to quality health care by keeping costs as low as possible, providing a reasonable level of benefits and providing quality customer service. Failure to meet these moral obligations may have financial implications. Member dissatisfaction may result in many members leaving the health plan, leaving the health plan without enough members to support the infrastructure.

Although health plans generally maintain several blocks of business, in this article, we will focus on the commercial insured block of business sold to individuals and groups since this block generally has the most financial impact. Also, health plans generally follow similar business practices for each block of business it manages.

Manual Rates

Health plans use manual rates to determine premium rates for individual health plans and small employer groups. Manual rates represent the health plan’s expected overall experience for the effective period, adjusted for policy-specific rating factors like benefit plan, area, and age-gender. Manual rates are developed in three phases: an analytical phase, a business decision phase, and a regulatory oversight phase.

During the analytical phase, the actuary starts by projecting past claims experience for the health plan to the future rating period. The projection usually reflects adjustments for:

- External factors like changes in clinical practice and in the economy

- Benefit, care management and other structural changes

- New legislation

- Price increases

- Fluctuations in experience due to large claims

- Changes in the disease burden for the risk pool that will not be reflected through other rating adjustments

Although each of these adjustments require considerable skill and care, the most difficult part of the process is often estimating the expected change in disease burden. Unpredictable changes in the disease burden are often the result of adverse selection. Typically, adverse selection occurs when a member enrolls in a plan, incurs a high number of claims, then drops coverage or moves to another health plan. Adverse selection may also occur if the rates favor one group over another. For example, if the rates are structured so that younger members subsidize older members, younger members may leave the health plan. If that occurs, the rates for the older members will be insufficient.

The actuary performs numerous tests during the rate development process to make sure the rates are indeed a best estimate, including comparing actual results to expected results in prior projections and explaining the variances. The test results are used to improve the projection process going forward.

A similar process is used to determine the expense portion of the premium, except that the underlying analysis is often based on the budget. The final premium is the projected claims, the projected expenses, and a provision for adverse deviation (PAD). PADs are usually expressed as a percent of premium. By law, the expense portion of the premium must meet loss ratio requirements.

The final decision as to what the premium rates should be is generally made with input from senior management in various areas like underwriting, finance, and sales. One of the key questions asked during this phase is how the health plans compare to rates from other companies. If the proposed rates are higher than the competition, then the health plan will most likely try to determine the reason for this. The health plan may want to lower the premiums to be more competitive. More sophisticated health plans will do additional testing at this point to determine whether or not this is a wise decision.

Once the final rates are determined, the actuary must file the rates with the state department of insurance and, for plans sold on the Exchanges, with the federal government. In the rate filing, the actuary has to attest that:

- The rates are adequate

- The rates are not overly conservative

- The rates are fair

- The rates and underlying plan designs comply with all state and Federal regulation

The degree of regulatory oversights varies considerably. In some states, the health plans can simply file and use the rates. In others, there is considerable scrutiny, including public hearings.

Experience Rating

If a health plan deems a group to be large enough to be fully credible, then the health plan relies solely on just the group’s past experience as the starting point for determining the premium rates. That experience is adjusted in a manner similar to that used for manual rates. In fact, the adjustment process and values are often identical to that used in the manual rating factor. In some cases, a group may be considered partially credible, which means that the initial premium rate is a blend of the manual rate and the experience-rated value.

Once the initial rate is determined, the decision-making process is similar to the one used in determining with manual rates, except that the final decision is made by individuals associated with the group rather than senior management. Also, some policy specific analytics may be done at this phase to estimate expected gains and losses.

The health plan must file rates on a regular basis, but there is no regulatory oversight at the policy level.

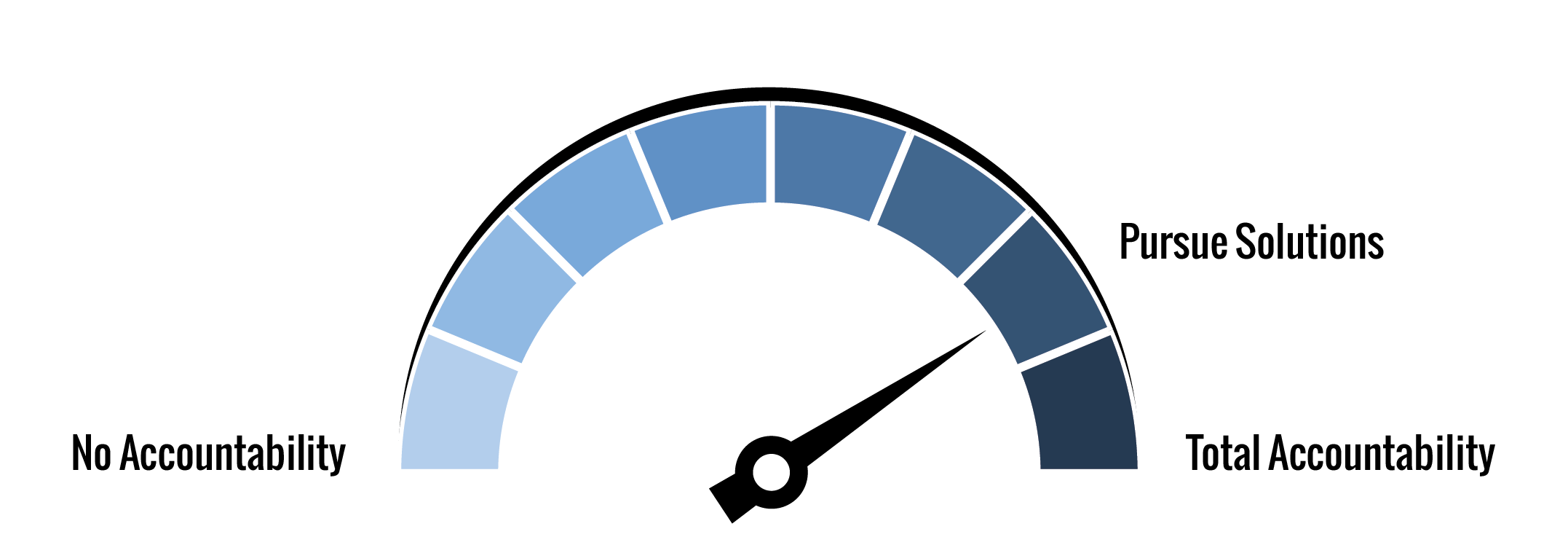

AHP Accountability Index and Health Plan

The Axene Health Partners Accountability Index (AAI) provides a consistent method for measuring how well an organization’s accountability mechanism meets it obligations as defined by the Triple Aim:

- Improving the patient experience of care (including quality and satisfaction)

- Improving the health of populations

- Reducing the per capita cost of health care

Our score for health plan rates is 79.2%, based on the following evaluation of typical practices:

| Triple Aim Category | Weight | Rating | Description |

| Patient Experience | 0.333 | 75.0% | The next step is to accept ownership and responsibility |

| Population Health | 0.333 | 75.0% | The next step is to accept ownership and responsibility |

| Cost of Care | 0.334 | 87.5% | Apply known solutions to predictive tasks and challenges |

| Overall | 1.000 | 79.2% |

Most health plans have an extensive infrastructure designed to ensure that a patient’s experience is positive. The infrastructure almost always includes on-line information about member benefits, customer service lines to answer questions, provider quality requirements, reporting, and member satisfaction surveys. Although the infrastructure is there, members are not entirely satisfied with the results. For example, according to the 2017 J.D. Power Member Health Survey1 25% of members are unsatisfied with the coordination among health plans and providers. This presents considerable growth opportunities for health plans willing to invest in improving their member experience infrastructure.

Similarly, most health plans have an infrastructure in place to improve population health through education and direct care. In some cases, a program may be available only to members. For example, a health plan may send out reminders to its members to receive a physical, mammogram or other preventive care. In other cases, a health plan may provide services to the local community through a foundation. Although these programs play an important role in improving the health of a population, there is considerable overlap between various efforts both inside a health plan and between health plans and other population health providers. We recommend health plans use the considerable data at their disposal to determine ways to improve the effectiveness of their programs and to optimize resources.

We ranked the cost of care category higher than the other two categories because health plans not only have a strong rate-making infrastructure in place, but there is also considerable internal and external oversight. That said, the overall cost of care is higher than most policy holders want to pay. More sophisticated health plans regularly review opportunities for lowering cost using methods like the AHP’s 24 Lever model2. One note. It is not only the overall cost level of health care that creates a problem for members, but also the year over year increases which may put health care out of reach at least for a while. Again, we recommend that health plans improve their analytical capabilities in an effort to minimize unnecessary swings.

Conclusions

Although health plans are generally well-run, there are still considerable opportunities to grow the bottom line, reduce the cost of care, and improve the patient experience. To some extent this can be done through on-going reviews of the process underlying the health plans infrastructure. More importantly, health plans have considerable data that can be mined to address key issues.

1http://www.jdpower.com/sites/default/files/2017065.pdf

2https://axenehp.com/the-24-lever-model-lowering-insurance-premiums/

About the Author

Joan Barrett, FSA, MAAA, is a consulting actuary with Axene Health Partners, LLC and is based in AHP’s New England office.