Summary

Throughout the United States, new health plans are emerging as provider systems and nontraditional organizations seek to enter the market. Licensure of these health plans happens at the state level, and typically requires some projection of financial results (such as projected financial statements), although the rules and their stringency vary from state to state. States may require substantial documentation of the data, methodology, and assumptions used to develop the financial projections. While it is important to meet the specific requirements of the individual state, there is a general approach to preparing these statements that can be used in most situations.

This material provides a general overview of what goes into the projected financial statements, with a more focused discussion of best practices for projecting the medical claims expense (which is frequently the most challenging projection to develop). It is assumed that the reader has a basic familiarity with financial statements – income statements, cash flow statements, and balance sheets – as well as with basic actuarial and insurance concepts.

Timing of the Financial Projection

Typically, the projection will be for five to seven years from the targeted effective or “go live” date of the health plan. A state may specify the minimum number of years required for the projected financial statements. It is best practice to develop financial statements on a monthly basis, with quarterly and annual summaries. It may also be required by the state to prepare financial statements for the period immediately preceding the effective date to account for expenses incurred prior to the commencement of plan operations.

Components of the Financial Projections

Here is a quick summary of the components of the financial projection:

- Enrollment or membership

- Claims expense (medical/pharmacy)

- Non-claims expense

- Federal income tax

Following are further details on developing these projections, along with suggestions for supporting documentation.

Enrollment or Membership

The basis for all of the projections is the expected size of the population to be covered by the new health plan. This includes an estimate of enrollment at the effective date of the plan, along with expectations for growth in future years.

There are several sources of information that can be used to support enrollment projections. Typically, the entity will have sought marketing reports or similar analysis to determine the size and concentration of the target market (e.g., current Medicare Advantage enrollees and total Medicare beneficiary count in County X). For entities that will partner with a health plan (e.g., limited Knox-Keene applicants in California), the health plan may have current enrollment estimates. Starting enrollment and anticipated year-over-year growth are typically set by entity leadership based on this input.

Claims Expense (Medical/Pharmacy)

A projection of expected claims activity is required to support the financial statement. Best practices suggest the following approach:

- Development of Actuarial Cost Model.

- Determination of Expected Incurred Claims Per Member, Per Month (PMPM) by Year.

- Modeling the Emergence of Paid Claims, Seasonality, and IBNR.

Each of these is described in further detail below.

Development of Actuarial Cost Model

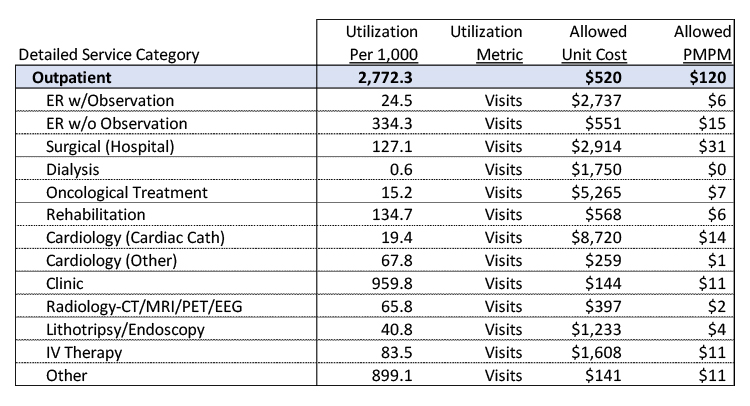

The actuarial cost model is the gold standard basis for projecting a plan’s costs, and may ultimately be used for a wide variety of purposes, including populating the projected financial statements. In its typical form, the cost model tabulates allowed unit costs and utilization for the target population at a detailed service level. Unit costs multiplied by utilization then results in the projected PMPM cost associated with that cost model.[1]

For those unfamiliar with actuarial cost models, below is an excerpt from a larger model, showing only the outpatient services (the full model includes inpatient, outpatient, professional, and pharmacy services). The full model was developed recently for a start-up health plan in California.

A full exposition of the development of the actuarial cost model is outside the scope of this writing, but some basic principles are described below:

- Sources of Data. Typically, the greatest challenge in developing a cost model is finding an appropriate dataset from which to generate basic unit cost and utilization values. In the absence of historical experience (such as from a potential partner plan), the cost model may be built from publicly available sources or normative databases typically managed by consultants. For example, for a proposed Medicare Advantage plan, the starting cost model might be developed from the CMS Limited Data Set (LDS) files for the specific county of interest. For a commercial plan, the starting cost model might be developed from a normative database from a consulting firm.

- Adjustments to Allowed Unit Cost.

- Unit cost trend – For Medicare and Medicaid cost models, trend may be obtained from public sources; for commercial models, there are numerous trend surveys published by consulting firms that may be referenced.

- Contracting – The financial projection should take into account the expect reimbursement level to providers under the plan.

- Other factors (e.g., DRG adjustment) – Other factors may apply under certain circumstances. For example, if strong care management is expected to reduce hospitalizations, it may be deduced that the remaining hospitalizations are at a more intensive level (i.e., higher DRG weight) than the original data would indicate.

- Adjustments to Utilization.

- Utilization trend – Generally relies on similar resources to the unit cost trend above

- Care management effectiveness – It is important to compare the care management effectiveness of the proposed plan against the care management reflected in the base population for the cost model. This may be a broad estimate or a more detailed assessment of specific programs and their expected impact.

- Population risk – Utilization of services will vary based on the underlying health risk of the population.

- Application of Benefits. For Medicare and commercial cost models, benefits and member cost-sharing may be applied at a detailed level in the actuarial cost model, or may be estimated at the plan level and applied to the overall PMPM.

A separate cost model should be developed for each year of the projection, taking into account changes in the factors listed above. Typically, the cost models are included and justified in a supporting actuarial report for documentation purposes. The original source of the cost model and the value and rationale for any adjustments should be included in the documentation.

Determination of Expected Incurred Claims PMPM by Year

The PMPM incurred claims can then be determined based on the values presented by the actuarial cost model. Other factors should then be addressed:

- Benefit Value. As noted above, benefits may be applied directly into the actuarial cost model. It is also common to estimate a benefit value by modeling expected benefits, or by examining plans currently offered in the marketplace.

- Provision for Adverse Deviation (PfAD). A provision for adverse deviation may be applied and should be explicitly described in the documentation.

- Stop Loss/Reinsurance. Expected recoveries from stop loss coverage should be incorporated into the incurred claims estimate.

The result is projected incurred claims PMPM for each year of the projection.

Modeling the Emergence of Paid Claims, Seasonality, and IBNR

When a new plan commences operations, there is generally a lag period between the start of the plan and the emergence of claims payments. This can dramatically affect the financial statement values at each month, so it is critical to have a systematic method for determining how quickly claims are paid. Claims also typically reflect seasonality – times of the year when there is historically higher or lower utilization than otherwise expected. Finally, at any given point, there will be claims that have been incurred but not paid – these claims are represented by an estimated IBNR value that should also be included in the financial statements. Following is a general approach to conducting and documenting these calculations:

- Determine the nature of the provider contract, and allocate incurred claims amounts accordingly. For example, while fee-for-service claims would be expected to show some lag in development, capitation might be assumed to be paid on a monthly basis with no lag.

- Project the emergence of fee-for-service claims based on an expected lag pattern. The most straightforward approach is to build an estimated lag triangle from the projected incurred claims PMPM and the expected lag pattern. The result is an estimate of paid claims by month.

- The ideal source of data for the expected lag pattern is the administrator/management services organization (MSO) that the entity expects to handle claims administration. If that information is not available, it may be appropriate to use normative experience from an actuarial database or the historical experience of a large operational plan.

- The lag pattern is built by month. Completion factors are developed for each month from incurral. The amounts paid for each month are calculated based on those completion factors, the projected incurred claims PMPM, and the projected enrollment in that month.

- Similarly, monthly seasonality estimates can be generated from the same data source and applied accordingly.

- Determine IBNR. The difference between the projected incurred claims and the estimated paid claims is the estimated IBNR.

- Over the course of the year, total paid claims plus the change in IBNR should be equivalent to the original projected incurred claims for that year.

“The emergence of paid claims is a critical determinant of early plan performance, and regulatory scrutiny should be expected.”

Methodology and supporting figures are typically described in the actuarial report supporting the projected financial statements. The emergence of paid claims is a critical determinant of early plan performance, and regulatory scrutiny should be expected.

Non-Claims Expense

Aside from the medical claims expense, other expenses should be accounted for in the financial statements. These non-claims expense items may include the following:

- Salaries, wages, and benefits

- Other expenses

- Rent

- Supplies

- Required insurance policies

- External support for services not covered by staff – IT, marketing, legal, audit, actuarial, consulting

- Plan management expenses

Non-claims expenses are typically estimated by the entity’s finance leadership based on current market conditions, contracts with outsourced vendors, and expected internal resource needs. At minimum, the value of each expense component should be documented. For certain items, the underlying assumptions should also be documented – for example, in calculating salaries, wages, and benefits, the composition of the underlying staff (including expected number of full time employees and salary values) should be documented.

Federal Income Tax

Similar to non-claims expenses, the treatment of federal income tax should be directed by the entity’s finance leadership and documented accordingly.

“It is absolutely critical to review the legal and regulatory framework and application instructions issued in the entity’s state.”

State Variations

As noted in the introduction to this material, rules vary from state to state regarding whether and what financial projections must be submitted in order to obtain licensure. Consider California, where such projections are covered specifically under the Knox-Keene Act of 1975, which requires projected income statements, cash flow statements, and balance sheets, as well as comprehensive supporting documentation, including a formal actuary’s report. It is absolutely critical to review the legal and regulatory framework and application instructions issued in the entity’s state.

Other Financial Requirements

This material does not address funding that may be required by the state to support reserves and/or risk-based capital requirements. Such requirements, particularly if funded through plan operations, should be incorporated into financial statements where applicable.

In Closing

This writing is intended to provide a general to-do list for preparing projected financial statements for a new health plan. However, it is by no means all-inclusive, and special characteristics of the particular plan or entity should be considered in applying these guidelines. For example, if the new plan includes multiple lines of business, geographic markets, or other divisions, the financial projections should be developed for each line first, and then added together to generate entity-wide projections.

[1]For a deeper exploration of what can be done with actuarial cost models, please see the Inspire article Building Actuarial Cost Models from Health Care Claims Data for Strategic Decision-Making(William Bednar).

About the Author

Guest Post – Elaine Corrough, FSA, FCA, MAAA

Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.