Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.

Happy Birthday ACA!

March 23, 2019 marks the ninth birthday of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), colloquially known as Obamacare. If we want to be exact, and we do, what we call a ninth birthday is really a tenth birthday, right? As the ACA begins it’s tenth year, it’s useful and instructive to consider the rocky path of its inaugural decade.

The layout of this article is a ranking of the first ten years of the ACA in a countdown-style format. The ranking order is obviously subjective in nature; details, references, and rationale are provided with each year. While I think the general indicators of the ACA’s high and low points are compelling, other commentators may logically choose a different ordering based on alternative measures. For example, I concerned myself with market sustainability devoid of future funding challenges and did not consider the impact on the federal deficit as a ranking variable. Also, I didn’t contemplate difficult-to-measure societal costs such as motivations for companies to limit the number of full-time employees or incentives for individuals to minimize personal income.

While this article is hopefully more entertaining than a typical health insurance research paper, it is not a novelty exercise; it’s a serious reflection of the ACA history, the challenges encountered, and the notable successes. Hopefully, it’s also engaging and jam-packed with insights (abundant references to time-relevant quotes and articles are included) to consider as the ACA prepares for its second decade.

Although the ACA has broad impact on the health care system, the endurance of the legislation relies on the sustainability of the individual market which it fundamentally reshaped in 2014. Accordingly, the rankings are aligned with individual market success and its outlook. Relevant factors include consumer satisfaction and popularity, enrollment success, flexibility to improve, functioning mechanics, general market confidence, insurer profitability, legal challenges and victories, number of participating insurers, operational aspects and premium levels.

On to the Countdown

#10. 2016

In the third and final year of ACA markets having the benefit of training wheels (reinsurance and risk corridors), it was clear that the ACA was not ready for the real world. Numerous complications arose after a relatively smooth-sailing prior year. Enrollment was less than half of its original projected size, the population was skewed (older and sicker), insurer losses were substantial, and there was no cohesive plan to address the challenges. Assessment of blame included “self-inflicted wounds by Obama and his administration”[1] as well as allegations directed toward the usual suspects.

2016 was also year that serious concerns regarding the ACA risk adjustment methodology became publicly apparent. In March, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) acknowledged this through facilitation of an industry conference and the release of a White Paper. Adjustments to the risk adjustment methodology dominated the annual 2018 regulation which was finalized in 2016, marking President Obama’s final fingerprints on his namesake law.

The risk adjustment challenges were so widespread that one of the first two Strategic Initiatives of the Society of Actuaries(SOA) Health Section Council (charged to investigate ACA markets and challenges) devoted its focus exclusively to ACA risk adjustment complications while downplaying other pervasive concerns. A series of papers from a diverse group of actuaries had a common theme and mirrored comments submitted in response to the proposed annual ACA regulation; the papers focused on risk adjustment inequities, volatility and solvency anxiety, and disadvantages for low cost insurers who effectively manage care. As the Trump administration navigates its way through the ongoing legal challenges, unresolved methodology concerns still remain today. The common theme expressed in the series of actuarial papers led to an unfortunate conclusion that “we all want young people to enroll in the market with only two exceptions: young people and the health plan that would likely enroll them”.[2]

In May, U.S. District Judge Rosemary Collyer ruled that the ACA’s cost-sharing reduction (CSRs) subsidies were not appropriated by Congress and billions of Treasury funds were unconstitutionally spent. While this decision was regarded as a large blow to the ACA, it had a Silver (pun intended) Lining that manifested in 2018.

The troubled market catalyzed proposals from Republicans in Congress that also included federal subsidies to support the individual market (direct federal funding for this market began with the ACA), but in the form of age-based tax credits rather than income-based subsidies and ACA-like mechanics[3].

Bad news seemed to repeat itself with CO-OP plans falling like dominoes and major companies exiting markets, prompting fear of some counties potentially having no insurers in place. Democrats joined Republicans in expressing doubts about the ACA’s structural mechanics. Minnesota Governor Mark Dayton stated that “the reality is the Affordable Care Act is no longer affordable”[4] and later utilized state funds to absolve some of the damages. At a campaign event in October, former President Bill Clinton referred to the ACA framework as a “crazy system” and said the subsidy structure (limited to certain income levels) in an inflated premium environment was “the craziest thing in the world”. His description of premium cliffs was visibly clear with a simple graph-plotting of premium rates by income level.

The best opportunity to correct ACA markets (without additional federal spending) in 2016 was the same as it is today. Section 1332 of the legislation allows states to develop innovation waivers and flex some of the ACA’s rigid rules to attract a broader population. Unfortunately, tangible opportunities were not well-communicated and promulgation of guidance was released too late for states to make sweeping changes for 2017. Also, the guidance was arbitrarily inflexible and offered little more than “reinsurance waiver” options which some states adopted. If allowed to be used appropriately, Section 1332 would allow states to correct premium subsidy imbalances and attract a broader market.

At the time, my assessment of the market outlook was gloomy due to regulatory inaction and lack of appropriate attention. I was concerned that stakeholders didn’t fully appreciate that the long-term market viability relied on financial fundamentals rather the pomp and circumstance of the ACA’s early years. I wrote “the most challenging period for the ACA is still ahead of us, with a riskier market for all participating health plans, waning enthusiasm as the initial promotional value wears off, and a new president who is not personally identifiable with the program. In my opinion, a long-term sustainability viewpoint will recognize the financial implications and inherent incentives, acknowledge the need of positive outcomes for both health plans and consumers, and appropriately discount the early emotional activity associated with this new marketplace”.

The difficult environment influenced the presidential election. In an exit poll, NBC reported that voters who thought the ACA was an overreach “are breaking decisively for Trump, 80 percent to 13 percent.”[5] Donald Trump’s victory obviously took some wind out of the ACA sails. In startling reality, his presidential actions have circuitously stabilized ACA marketplaces; but Mr. Trump was elected under a mantra of ‘repealing and replacing’ the ACA, and expectations were clearly in sync with his campaign platform. The year ended with ACA markets in rough shape, insurer exits and high premium increases, consumer frustration, and anticipation that the remaining days of the ACA experiment were numbered.

#9. 2013

Near the end of 2013, the implementation efforts came into public view. The beginning stage of ACA operations did not align with its solid legislative and legal successes. As many states declined to establish their own exchanges, the majority of states relied on the federal exchange model. Initial reports of ‘website is experiencing technical difficulties’ were soon discovered to be grossly understated. The implementation rollout was disastrous and President Obama’s first appointed HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius accepted responsibility for the debacle, saying “You deserve better…I apologize…I’m accountable to you for fixing these problems and I’m committed to earning your confidence back by fixing the site.” Predictability, initial enrollment was light and skewed toward older enrollees more likely to have medical conditions.

The year ended badly on other fronts as well. After earning the Politifact.com ‘Lie of the Year’ award with ”If you like your health care plan, you’ll be able to keep your health care plan”, President Obama allowed states to extend ‘transitional’ (aka grandmothered) plans for several more years, effectively changing the ACA enrollment dynamics. By this time, insurers had already locked and loaded their initial rates for ACA markets, and the rule change caught insurers and their actuaries off-guard. The mid-year changes plagued markets in the initial years; insurers rely on tight margins with premiums established well in advance. Insurers need to understand the rules up-front to appropriately develop annual premium rates. While it’s tempting to immediately solve an isolated problem, “government leaders could logically be insensitive to potentially inflicting market damage” and wound government’s reputation as a reliable business partner.

Key stakeholders were troubled as well. A controversial 2.3% excise tax on medical devices in the ACA legislation went into effect on 2013. Labor unions said the ACA was highly disruptive, claiming it would drive up the costs of union-sponsored plans, “ACA will shatter not only our hard-earned health benefits, but destroy the foundation of the 40-hour work week that is the backbone of the American middle class.”[6]

After building momentum through the pre-implementation years, 2013 was a setback and clearly the ACA’s worst year before going live in 2014.

#8. 2017

2017 will forever be known as the ACA’s year of high rate increases and the failure of repeal efforts. It’s also the only year of the ACA beyond the ‘training wheels’ phase when insurers were reimbursed for CSR payments, and the limited one-year metric did not indicate the unadjusted ACA framework was sustainable. Insurers exited ACA markets, and the uninsured rate began its post-ACA climb. In the second round of the SOA Health Section Strategic Initiatives focused on ACA markets, a 2017 article noted “It is often asked if the individual market is sustainable long term and if these issues can be fixed”.[7]

The year began with President Trump’s first executive order directing the Health and Human Services agency “to interpret regulations as loosely as allowed to minimize the financial burden on individuals, insurers, health care providers”.[8] This set a new direction that provided expanded market flexibility. Much of the 2017 focus, however, was on federal legislative repeal efforts.

The other initial Strategic Initiative (“Evolution of the Health Actuary”)of the SOAHealth Section Council was led by my colleague Joan Barrett. In writing about the state of individual markets and potential legislative disruptions, she spoke of high rate increases, insurers dropping out of markets, and levels of market uncertainty that one would might think would be appropriate in 2014, not three years into the program. I echoed these comments on a podcast about Section 1332 waivers, “I don’t think anyone really believes that the markets have settled, and the waivers actually could bring some stability to the markets if they are tailored in the right way.”

Despite warnings to the contrary, the ACA was unwaveringly touted as a one-size-fits-all solution for everyone not eligible for other coverage. In reality, the unbalanced incentives caused the market to fall 12% short of the required 40% of enrollees in the 18-34 age rate. In June, the former Acting Administrator of the CMS Andy Slavitt acknowledged recognition of the imbalance and his satisfaction with the uneven pricing dynamics producing winners and losers. In an interview with National Public Radio, he said “The problem our country has is how to help people who are in the lowest economic straits, who have the most health challenges, get access to affordable coverage and, indeed, get well. The problem we don’t have is how to help 27-year-olds get cheaper insurance. That’s just not a national concern for us right now.”[9]

That admission was a far cry from ACA-architect David Cutler in 2013 advocating that ACA markets would be attractive to young men, “I don’t think it (3:1 age curve) will have a huge impact because it will be offset by the subsidies. Many young men have relatively low incomes. Thus, the premium they face will not be the full amount, but rather the amount net of the subsidy. Put another way, the ACA has limits on the share of income that people will pay for health insurance. These limits are sufficiently low that the price will not be a prohibitive factor in determining whether to buy coverage or not”.[10]

While the mechanical combination of the ACA rating rules and unbalanced premium subsidies continued to afflict markets, legislator attention on market challenges was uncannily misdirected toward a “secret sabotage document” that sought to close loopholes and was quite underwhelming from a scandalous viewpoint. With relief not coming through federal legislation or robust Section 1332 efforts, two unlikely remedies surfaced in 2017.

In May, an actuarial study revealed that the demographic imbalance might be partially resolved by employers accessing the individual market for their employees. Notably, this activity suggested that individual markets offered some attractive value for employers.[11]Key findings of the study included:

- Relative to expectations and alleged sustainability requirements, the ACA did not attract the targeted cross section of members in the individual market. The rating requirements and the unbalanced allocation of tax subsidies attracted an older and sicker population. This resulted in higher average costs and less favorable risk adjustment settlements for insurers, both of which have necessarily increased future premium rates.

- With the current framework and resulting population, the individual market will continue to struggle with sustainability. Population changes could be brought about by different incentive structures through legislation, intelligent use of waivers via Section 1332, or through employer subsidies and material changes in distribution channels.

- Migration of workers from the traditional group market to the individual market will lower the average age and increase stability in the individual market.

In October, President Trump stopped reimbursing insurers for CSR payments after receiving a legal recommendation from the Department of Justice. The market benefit of this action had been previously discussed, but general public understanding of the paradoxical implications and market benefits is lacking, even in today’s lower premium environment.

2017 ended with tax legislation that repealed the individual mandate penalty (effective in 2019), concerning some stakeholders and putting the 2012 Supreme Court decision back into focus. Overall, it was a bad year for the ACA. A significant improvement in financial results, stemming from large rate increases, is the only factor that keeps 2017 in the single digits on this list.

#7. 2014

The enrollment implications of the ACA’s rating rules and pricing mechanics came into view, with influences from the Supreme Court ruling on mandatory Medicaid expansion and President Obama’s decision to allow transitional plans. The regulatory rating rules flirted with violations of actuarial principles, which the ACA tried to overcome with a mix of federal subsidies, a shared-responsibility payment requirement for those avoiding coverage, and general promotional efforts. The first of the three is the lifeblood of the market, and the market would collapse without this financial assistance. The second was weak and largely unenforced before being repealed. The third had some short-term value but fundamentally does not offer long-term value or sustain markets.

Rather than directly addressing the “important” problem of high health care costs, the ACA provided financial incentives for low income individuals to obtain health insurance coverage, but simultaneously created an “urgent” problem of disrupted insurance markets, which shifted focus away from the more important problem.

The ACA’s redesign of market rules complemented with an allotment of federal funds was effective in providing insurance incentives to previously uninsured individuals. At the same time, it increased premiums and disadvantaged some prior individual market consumers. The unbalanced incentives created a skewed market and sustainability challenges.

Whether or not commentators believe it is the right social policy, almost everyone agrees that the ACA’s largest challenge is the disallowance of health status as a classification of pricing risk. In highlighting the dangers of broad risk classes in a general insurance sense, Actuarial Standard Of Practice No. 12 warns in the background section: “Failure to adhere to actuarial principles regarding risk classification for voluntary coverages can result in underutilization of the financial or personal security system by, and thus lack of coverage for, lower risk individuals, and can result in coverage at insufficient rates for higher risk individuals, which threatens the viability of the entire system.” Actuarial principles are not theoretical ideas that can be overcome by sheer force in a practical world. Highlighting the importance of actuarial mechanics, WellPoint Chief Executive Joseph Swedishadmitted “the critical ingredient in terms of how our business operates…. without actuarial analysis, we really are shooting in the dark.” The actuarial implications were decipherable , and expected to change enrollment dynamics of individual and group markets.

HHS Secretary Sebelius announced her resignation in April and left the post in June. Her replacement Sylvia Burwell was favorably viewed as a capable administrator, less partisan and possessing less animus toward the insurance industry than her predecessor. She served for the remainder of President’s Obama time in office.

A public relations nightmare occurred later in the year. Rich Weinstein, a Philadelphia-based investment advisor researching his options after his insurance plan was cancelled for not meeting ACA standards, uncovered an incriminating video. It contained footage of one the primary ACA architects stating that the ACA would not have passed had its promoters been honest with the public. Dr. Jonathan Gruber, a MIT professor noted for building econometric models for state insurance exchanges, was a consultant engaged by the Obama administration to help craft the ACA. At an academic conference explaining the ACA development, he said “This bill was written in a tortured way to make sure the CBO did not score the mandate as taxes…Lack of transparency is a huge political advantage. Call it the stupidity of the America voter, or whatever.” Unsurprisingly, Dr. Gruber’s role in the ACA was largely downplayed by the Democratic political class after the video surfaced. Mr. Weinstein also discovered Dr. Gruber’s comments which eventually led to the Supreme Court ruling on the applicability of premium subsidies in federal exchange markets. This exposure was obviously damaging to the reputation of the self-proclaimed “most transparent administration” in history.[12]

Going into 2014, many consumers without health insurance or dissatisfied with their current coverage were cautiously optimistic about the new markets. Most prospective enrollees hadn’t read the details of the legislation, so they didn’t grasp the impact of the rating rules and the premium subsidy dynamics until they started shopping. When they shopped, their shopping was limited to their own insurance options, so their perspectives were likewise limited. Of course, the ACA impacted everyone differently, so everyone had different opinions. Due to the high cost of health care, sentiments were strong on both sides. Depending on where a consumer lived, his or her age and income, the ACA may have provided an easier opportunity to obtain health insurance. At the same time, a consumer might have been satisfied before the ACA and had their premiums doubled for a higher deductible plan with a skinnier network. ‘Affordability’ didn’t really translate to everyone, so initial consumer satisfaction with the law and the validation of the claim of ‘affordability’ was a bit of a mixed bag.

#6. 2010

Americans have always been deeply divided on the appropriate level of government involvement. Due to its emotional nature, those seeking a heavier hand have historically viewed health care as an opportunity to make inroads. In 1961, Ronald Reagan said “One of the traditional methods of imposing statism or socialism on a people has been by way of medicine. It’s very easy to disguise a medical program as a humanitarian project, most people are a little reluctant to oppose anything that suggests medical care for people who possibly can’t afford it.”

The ACA legislation was divisive and contentious from the beginning. The vitriolic accusations of problems in the health care system wasn’t limited to political opponents. In his first State of the Union address, President Obama said that his health care overhaul would “protect every American from the worst practices of the insurance industry.” Americans were sympathetic toward that accusation, as it came on the heels of a 39% premium increase that was later determined to include calculation errors. The legislation was unquestionably partisan and garnered no Republican votes. House Republican leader John Boehner said Americans “are angry that no matter how they engage in this debate, this body moves forward against their will.”

A lack of legislative consensus is usually followed by implementation and legal challenges, so it wasn’t hard to predict future turmoil. As I wrote about the importance of consensus in 2017, “Major legislation that lacks consensus often presents execution challenges. The ACA was passed by the narrowest of margins. In fact, the replacement of a US Senator changed the political makeup in the Senate, and the House of Representatives accepted the Senate bill without modification to avoid the Senate having to vote again. Many ‘drafting errors’, which would normally be resolved through a conference committee, remained in the final legislation. Due to a lack of continued lack of consensus, many issues (that virtually everyone acknowledges are real problems) remain unresolved. This was not a surprise to health care economist Michael Bertaut, who summarily concluded “a bill that essentially rerouted $3 trillion a year and reformed every facet of healthcare in the United States would guarantee endless warfare.”

In a SOA Health Watch interview published in September, Grace-Marie Turner[13] said “You know you had 30 percent approval for passage of this legislation, so you’ve passed a major overhaul of the health care system with the majority of the American people opposed. I think that makes it so much more difficult for this to work and for people to accept it, and we are a law-abiding country.”[14]

While the ACA remains a deeply divisive issue today, Americans are more accepting of its place in the health care landscape. Many people still object to the legislation, but they find it more tolerable in a less heavy-handed environment. Some ACA proponents are concerned with the new “escape options” available (while seemingly having little problem with the old ones), but the goodwill may actually help the ACA more than it hurts it. With these changes, the ACA is more popular than it’s ever been, but it took nine years and equally divisive modifications that were violative of original ACA ideals to get here. Let’s hope that the next major structural change in our health care landscape commences with a larger degree of consensus.

#5. 2011

While 2011 was the only quiet year in the public sphere, those in the insurance industry alternatively referred to the ACA as the AEA. That’s the Actuarial Employment Act, and the characterization was a fair assessment. Federal grants for Rate Review brought premium mechanics into the public spotlight. States were pushing back on the restrictive minimum loss ratio (MLR) requirements. Notably, Florida’s Insurance Commissioner expressed unease with the requirement likely reducing the involvement of insurance agents in the process, stating “I am especially concerned about how the MLR requirements will affect the role of health care agents who are critically necessary to help consumers in this increasingly complicated health care landscape”.

Insurers who were not well-positioned to participate in ACA markets were investigating how the ACA might damage their competitiveness. Through a consulting engagement, a pivotal moment in my career was catalyzed by a detailed analysis of ACA mechanics. After completing this project, my day-to-day work gradually shifted from tactical calculations to strategic assessments of market dynamics.

In November, theSupreme Court agreed to hear arguments brought by 26 states and the National Federation of Independent Business alleging that elements (including the individual mandate) of the ACA were unconstitutional. From a market sustainability standpoint, the American Academy of Actuaries went on record stating the individual mandate (or an alternative mechanism that would “encourage broader participation”) was essential. Plaintiffs in Texas v. Azar (2018) referenced the Academy’s position in their arguments against severability.

#4. 2012

In the year of President Obama’s re-election, the ACA survived a monumental federalism-based challenge with a landmark 5-4 Supreme Court decision that memorialized the shared responsibility payment as a legitimate “tax” assessed by Congress. The decision energized ACA supporters and renewed excitement toward the 2014 kickoff.

#3. 2015

At the five-year mark, the SOA Health Section published The ACA@5: An Actuarial Retrospective. As I wrote[15] in 2016, it “provided a comprehensive look back at the work of actuaries related to the implementation of the ACA. At the time, there was a general sense of cautious optimism regarding the ACA. The early implementation struggles had been resolved; market participation was active for buyers and sellers; and several legal battles that reached the U.S. Supreme Court had been weathered”.[16] An interesting and concerning observation of changing dynamics in one phase of actuarial work was presented by regulators, “What used to be a purely analytical exercise is now peppered with political overtones…The fact that a rate increase is actuarially justified may not mean that it is politically palatable”.

While certainly not out of the woods, there was cautious optimism as operational aspects had been fixed and many insurers who took a ‘wait and see’ approach in year one participated in year two. Enrollment also grew, as it had taken some consumers time to warm up to the new markets.

The ACA had its second major Supreme Court battle, this one regarding the allowance of crucial premium subsidies to continue to flow to federally-based exchanges. Premium subsidies, the lifeblood of the ACA markets, made the ACA a front page story again after a period of ACA quietness in the news cycle. A court decision, precipitated by Mr. Gruber’s comments on subsidy eligibility, had ruled “that the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) had broadened the ACA language ‘an Exchange established by the State’ to also include fallback exchanges established by the federal government (in states that did not establish an exchange) with regard to the issuance of government subsidies (technically ‘tax credits’) to assist individuals with health insurance premiums and benefit cost sharing.” The Supreme Court overruled this decision.

The annual premiere meeting of health actuaries featured a well-received session which included House Budget Committee Chair and future HHS Secretary Tom Price. He spoke about legislative goals of establishing equity between individual and group markets.

After a challenging beginning, ACA markets rebounded in 2015 with more insurer confidence and enrollment increases driving the uninsured rate down. The market improvements and a second major Supreme Court victory resulted in 2015 being an overall good year for the ACA.

#2. 2018

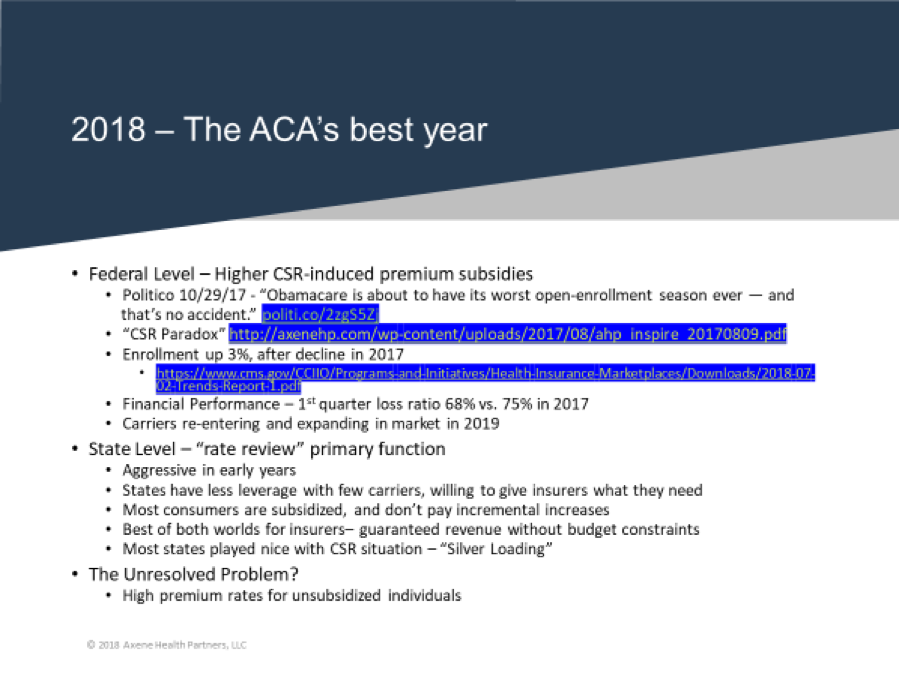

The largest and swiftest annual market improvement occurred in 2018. The impact of the improved financing clearly outweighed the scaling back of promotional efforts which was alleged to foretell the worst open-enrollment season ever. The improved dynamics surprised many commentators.

The catalyst for the change in direction was President Trump’s decision to discontinue CSR funding, which paradoxically benefitted markets. This decision received encouragement from several of his critics who took the time to understand its subtleties, but the directional ramifications were mostly misunderstood by others. While the false narrative around the CSR impact caused some consumer confusion, some of us took time to assist consumers and explain the new benefits and options to the general public.

The change marked a pivotal point in The Evolution Of The Individual Market, as “the favorable new environment attracted enrollment in 2018 that was larger than expected by some observers, particularly those who give more credence to nonfinancial measures such as government- sponsored outreach efforts.” The market results generated some surprises. While enrollment significantly exceeded expectations, insurer profitability skyrocketed to record levels. In October, new Section 1332 guidance brought additional interest to the improving markets. Larry Levitt of the Kaiser Family Foundation plainly described the settled environment in November, “At this point, the market looks pretty stable.”

In the final article for the second ACA-focused Strategic Initiative, I answered the earlier question about whether the ACA was sustainable:

“The enhanced premium subsidies have made coverage for low-income enrollees more attractive and have likely improved the risk mix. 2018 enrollment was more robust than many commentators expected, and the uninsured rate fell after rising in 2017. Insurers are experiencing record profitability, and that is reflected in the rate reduction in 2019. Competition is returning, and consumer popularity is also increasing. Polling should continue to rise as more people learn of the repeal of the individual mandate, which was consistently regarded as the ACA’s least popular provision. The expansion of alternative options won’t help ACA market enrollment, but it will likely improve consumer sentiment for those individuals who have been unable to find an ACA solution. The improved market dynamics, a split Congress and increasing popularity affirmatively answer the question posed throughout this series: Is the individual market sustainable in the long-term?”

In a presentation to actuaries in the summer, I claimed that 2018 was the ACA’s best year. For reasons we are about to find out, it didn’t hold the #1 slot very long.

#1. 2019

After a mass exodus in 2017 and 2018, insurers returned to ACA markets in 2019. The beneficial market changes reignited interest, and the number of state-levels insurers increased 17% in 2019 after a 28% reduction in 2017 and a 21% reduction in 2018. Despite the warnings regarding repeal of the individual mandate penalty, insurers were not skittish to return. In fact, they did so with premiums 2% lower than 2018.

In 2019, nearly 80% of eligible enrollees were again able to obtain coverage for less than $75 per month, and enrollment in ACA markets remains steady. Legislative disruption, which could generate more unintended consequences, is unlikely to materialize in the split Congress. The new environment is also more accepted by the health insurance industry.

The lower premiums, the greater competition, and the flexibility to purchase off-market options has led to increasing popularity and a signaling of long-term stability. A split Congress and improved consumer satisfaction have calmed the potential of any serious repeal efforts. Most states that missed the CSR-based opportunities in 2018 righted that ship in 2019.

Additionally, the new waiver flexibility signals further improvement opportunities in 2020. Leveraging the market turnaround in 2018, attracting more carriers, and providing states the opportunity to broaden their market appeal within the ACA framework make 2019 the ACA’s best year yet.

As I said in the latest Strategic Initiative article, “the single risk pool dogma has softened. There is growing recognition that the individual market can run on the fuel from premium subsidies rather than government coercion. Solutions involving ‘splitting risk pools’ are no longer automatically viewed as attempts to undermine the ACA and have been floated (along with solutions within risk pool) as policy proposals by both major political parties.” David Anderson, an academic thought leader on ACA dynamics, argues “a cap and a split market are not necessarily opposing policies.”

2019 will be remembered as the year that helped those most harmed by the ACA. While the 2018 CSR action significantly boosted financial assistance for lower-income consumers, it did nothing to help people ineligible for premium subsidies, the group most harmed. David Anderson aptly calls these people “the only ones without help”. The recent relief for this group, including the striking of the penalty for avoiding ACA markets and allowing off-market alternative options to be utilized, improves these consumers’ situations albeit through non-ACA solutions. It’s not a perfect scenario by any stretch. Like the ACA itself, President Trump’s footprint of ‘improvement for some and exit opportunities for others’ is clunky. It’s not a strategic policy framework, but a series of disjointed changes that has favorably shifted the rules for the market’s two significant eligible population groups. Nevertheless, it has transformed the 2016-2017 environment and improved the ACA’s outlook. The catalyst for the ACA legislation itself was ‘a critical mass of people without solutions in the marketplace of last resort’. You know what the catalyst for ACA repeal is? It’s the same thing; ‘a critical mass of people without solutions in the marketplace of last resort’. We will likely not all agree on what “solutions” are, but today we have more popular ACA markets, lower premiums, more participating insurers, people not be forced to purchase overpriced health insurance products, and perhaps a lower uninsured rate. We’ll have to wait and see for the last one. The ACA initially provided new solutions for the previously uninsured but left ‘a critical mass of people without solutions’. We can’t say for certain that this problem was solved in 2019, but the outlook is certainly better than previous years.

2019 should be a solid year for the ACA in all measures. 2020 should be better, but there will be more state variation as states learn how to leverage the new ACA dynamics at different speeds.

Concluding Thoughts

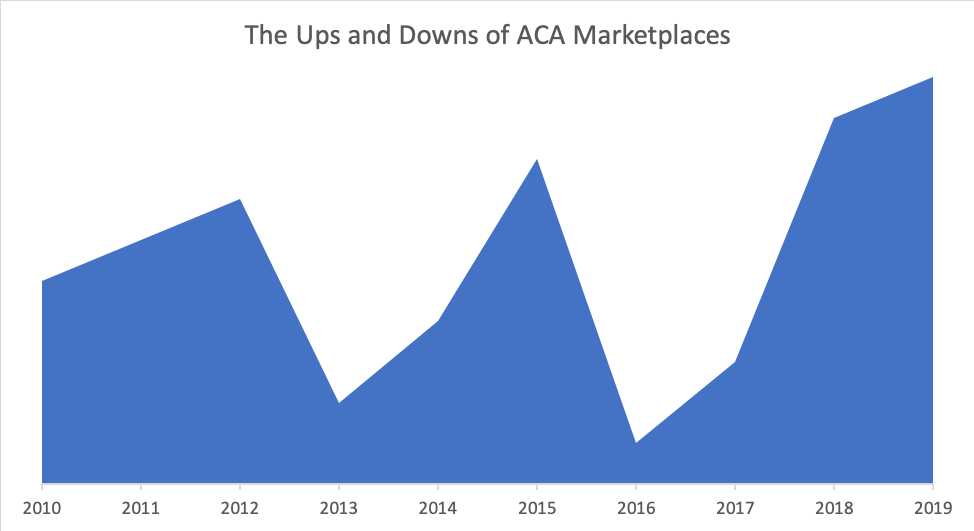

The chart below chronologically shows the performance reflected in the countdown. Notable setbacks have been the operational challenge of exchange implementation in 2013 and the financial challenges along with lackluster interest in ACA markets in 2016. The recent market success is largely due to divergence from the original ACA ideals, which includes increased funding through a paradoxical channel and allowances to utilize non-ACA coverages for the population without reasonable ACA solutions.

At its core, the ACA is still the ACA. The problematic dynamics that plagued markets in 2016 and 2017 are still embedded in the insurance mechanics in 2019. We still have the family glitch. We still have subsidy cliffs. We still have no ACA-compliant solution for people that earn more than 400% of the Federal Poverty Level. We still have the goofiness of inverted age curves that lead to only older people having free coverage. A legislative solution in a split Congress is unlikely, and tentative “bipartisan” agreements in recent years have not seriously addressed the ACA’s structural issues. Fortunately, there is little else that needs to be done at the federal level right now. The new stability in the ACA markets, opportunities to optimize enhanced federal subsidies, and new innovation opportunities clearly puts the ball in the states’ court. The state opportunities to leverage the enhanced federal funding and address the ACA’s unintended consequences are tremendous.

The ACA has had its share of bumps and bruises, but it’s lasted and persevered through the changing political landscape. While it hasn’t offered solutions for everyone, it has provided strong incentives for many previously insured people to obtain health insurance. It has also clearly created problems and we should all acknowledge that, even if it has enormously benefited us personally or the people we care most about.

The ACA’s recent success relies on humility. It works great for some people, but right now (without Section 1332 properly implemented), it doesn’t work for others, and there are better options out there for a small minority of the population. Recent efforts to demonize everything that’s not ACA-centered to detract from the ACA’s shortcomings is unfortunate and an unnecessary course of action toward long-term sustainability. We can champion ACA markets, but we should recognize that ACA markets are overpriced with income-based incentives, and that actuarially-priced markets targeting those with poor ACA incentives can peacefully coexist.

I am sometimes asked, “What is the key to understanding ACA dynamics?”. I always smile and say, “Never start with intentions”. The paradoxical impact of CSR defunding is not a quirk that states were able to sneak into the process. It’s intrinsic in the ACA math. In 2014, I explained why older individuals would pay less than younger individuals at the same income level for the same level of coverage. In 2015, I explained why high premium rate increases would result in some individuals actually paying less due to the subsidy structure. In 2018 (published in 2019), I explained why steepening the age curve to attract young adults may actually result in younger people paying relatively more. In 2019, I explained why a 2% aggregate premium reduction with more competition would actually result in some people having to choose between a higher premium or changing insurers. ACA math works in unintended directions (it’s not fully understood but it’s not a huge secret either), and implications are almost always misrepresented in the public sphere, sometimes carelessly but without intent.

In some circles, Democrats have been accused of deliberately constructing an unworkable program in hopes of spring boarding toward a more government-centric framework. Likewise, Republicans have been accused of ‘sabotaging the ACA at every turn’. I don’t know definitively if either of these accusations warrant investigation, but it’s not a relevant question in assessing the ACA markets and consideration of such would only pollute the results of the unspoiled countdown you just read. If you take off your politically-tinted glasses and look at the ACA landscape via a reasonable assessment of objective measures, you’ll realize that the ACA markets are stronger than they have ever been. The conjecture that no one wanted things to turn out this way is completely irrelevant. The ACA is about to have its best birthday ever, even if it is celebrated alone.

Endnotes

[1]https://www.politico.com/agenda/story/2016/07/obamacare-exchanges-states-north-carolina-000162

[2]https://www.soa.org/Library/Newsletters/Health-Watch-Newsletter/2016/november/hsn-2016-iss-81-fann.aspx

[3]ACA subsidies are not directly determined as tax credits would be. They are unknown during rate development and the resulting difference of market premiums and a fixed contribution tied to a benchmark plan.

[4]https://minnesota.cbslocal.com/2016/10/12/gov-dayton-affordable-care-act/

[5]https://www.nbcnews.com/card/nbc-news-exit-poll-results-large-share-voters-feel-obamacare-n680451

[6]https://blogs.wsj.com/corporate-intelligence/2013/07/12/union-letter-obamacare-will-destroy-the-very-health-and-wellbeing-of-workers/

[7]https://theactuarymagazine.org/creating-stability-unstable-times/

[8]http://www.trend-chaser.com/politics/president-trumps-productive-first-week-in-the-oval-office/?chrome=1

[9]https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/06/23/534106319/what-the-man-who-ran-obamacare-thinks-about-the-republican-health-plan

[10]https://www.soa.org/Library/Newsletters/Health-Watch-Newsletter/2013/october/hsn-2013-iss73.pdf

[11]It remains to be seen whether legislation (21stCentury Cures Act) 2018 HRA regulatory action will spur employer growth in individual markets.

[12]https://thehill.com/blogs/blog-briefing-room/news/283335-obama-this-is-the-most-transparent-administration-in-history

[13]Founder of the Galen Institute, an advocacy group promoting free markets in the health care sector.

[14]https://www.soa.org/library/newsletters/health-watch-newsletter/2010/september/hsn-2010-iss64-draaghtel.pdf

[15]https://www.soa.org/Library/Newsletters/Health-Watch-Newsletter/2016/november/hsn-2016-iss-81-fann.aspx

[16]https://www.soa.org/Library/Newsletters/Health-Watch-Newsletter/2016/november/hsn-2016-iss-81-fann.aspx

About the Author