The U.S. healthcare system pre-dominantly operates using a Fee-For-Service (FFS) reimbursement model. This means doctors, hospitals, and other healthcare providers are reimbursed per healthcare service provided to patients. One of the commonly cited weaknesses of the FFS model is the incentive for providers to perform too many services (i.e., over-utilization). The more services doctors and hospitals provide, the more payment they receive from the patient’s insurer. For the better part of the last decade, our work has focused on designing and implementing alternative reimbursement programs to reward providers for avoiding unnecessary services the FFS model encourages.

What we had not given any thought to, up until the last couple of weeks, is what happens when the FFS model fails in the other direction (i.e., under-utilization). With thousands of people receiving emergency treatment for COVID-19, it seems logical that revenues for hospitals and doctor offices should be soaring. However, that is not the case at all and, in fact, the opposite is happening. It sounds counter-intuitive at a time when our healthcare system is at its busiest, healthcare provider revenue has been sharply declining, putting providers at great financial risk. Some hospitals and medical groups have even gone as far as furloughing staff because their source of income has dried up so quickly. It is unthinkable hospitals would have to consider cutting their staff when there is a severe shortage of intensive care unit (ICU) hospitals beds, ventilators, and nurses/doctors to provide care for patients suffering from COVID-19, but they face little choice because they are running out of money.

Several factors are causing this to be the case:

Canceling of Non-Essential Care – Similar to restaurants and retail stores, most states have now asked or required hospitals and doctor offices to cancel all non-essential services to help prevent or slow the spread of COVID-19. In an FFS environment, every canceled service equates to lost revenue which then leads to insufficient funds being available to meet providers’ expense obligations. Some of these services are merely being delayed, but we know from other events that temporarily suppress demand, such as hurricanes and blizzards, some of the care will simply disappear completely.

Essential versus Elective Service Reimbursement – Elective services tend to be more lucrative than emergent services. For example, compared to the resources involved, hospitals are reimbursed much better for a knee or hip replacement than they are for a respiratory emergency like you see for COVID-19. A hospital at 100% capacity with COVID-19 patients will likely be seeing substantially less revenue than when they are at 80 – 90% capacity with a typical mix of patients.

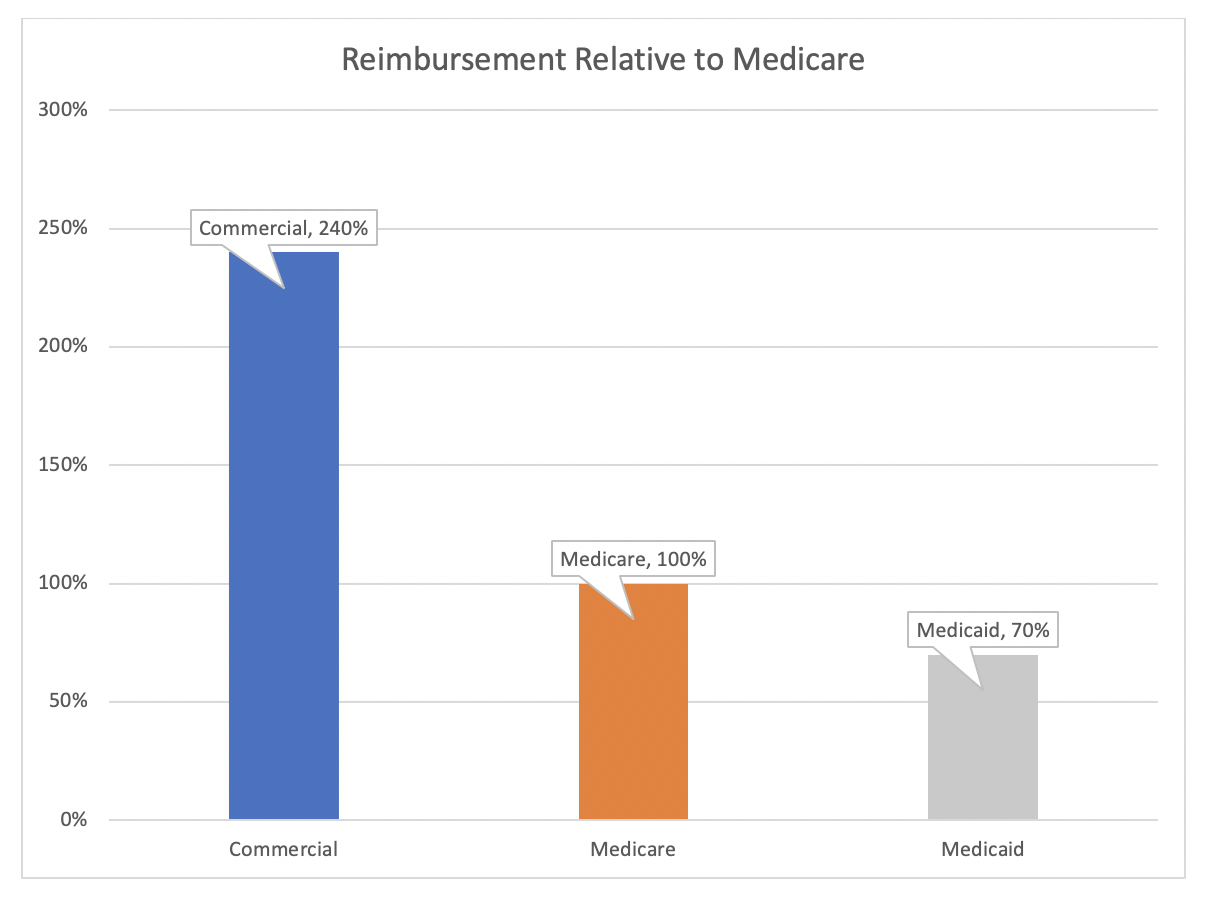

Payer Reimbursement Differentials – Commercial insurance reimbursement is generally far richer than government programs – a hospital will often receive 2 to 3 times the reimbursement from private insurance than they do from Medicare or Medicaid.

Figure 1: Reimbursement Levels

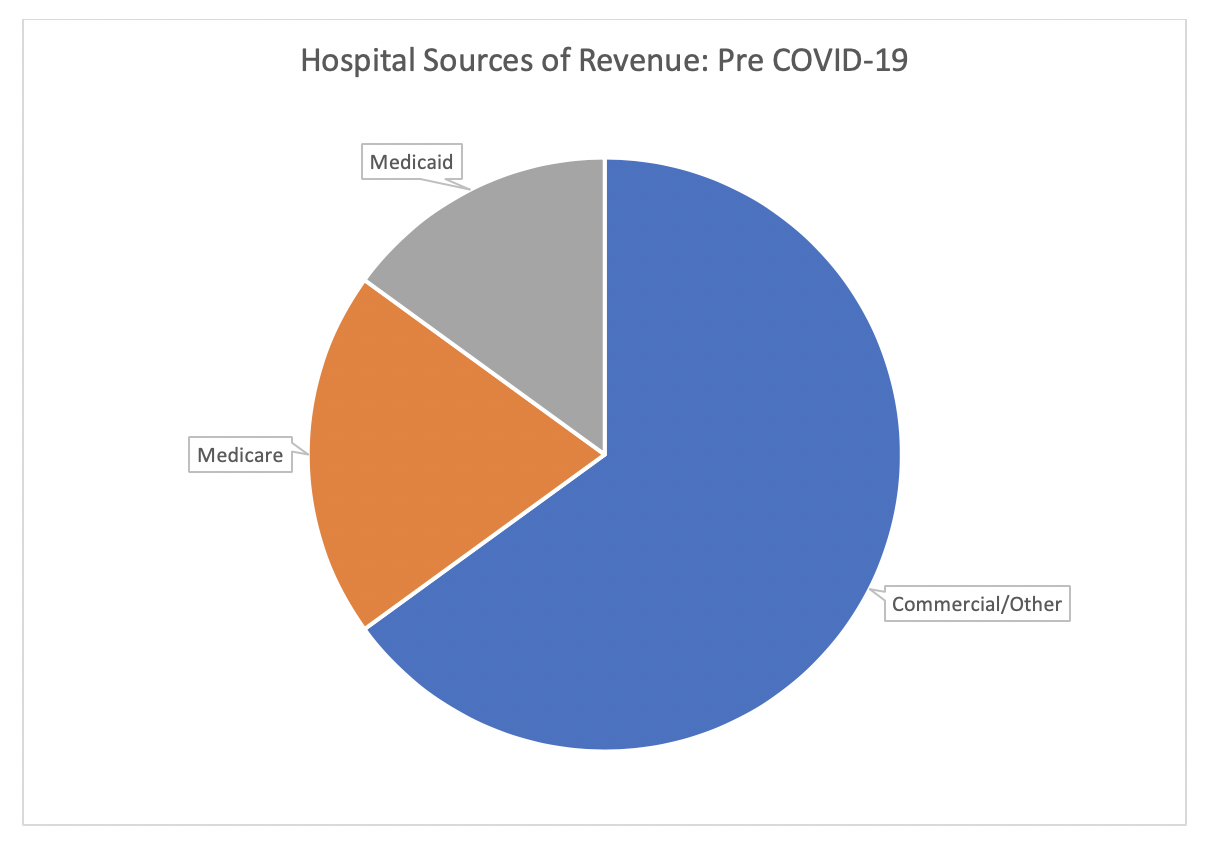

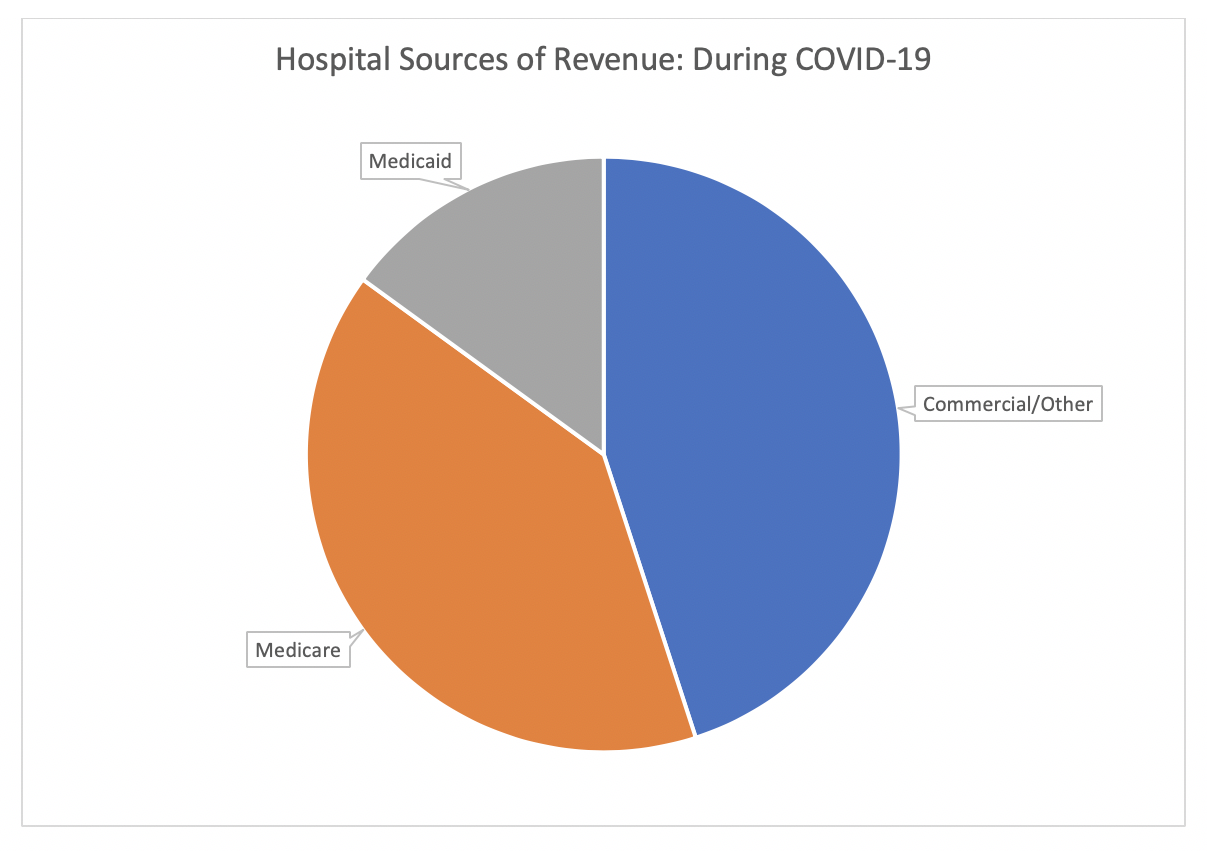

As a result, the majority of its revenue typically comes from non-government sources. Given the demographics that are hit the hardest by the COVID-19 pandemic, we can expect that hospitals will be disproportionately filled with Medicare patients which will further suppress their revenues. Figures 2 and 3 below show how the sources of revenue can shift before and during the pandemic.

Figure 2: Sources of Revenue Pre Pandemic

Figure 3: Sources of Revenue During Pandemic

Timing of Payment – It is standard for hospitals to send detailed invoices to insurance companies after a patient is discharged from the hospital. The insurance company then reviews the invoice and processes the payment. The larger the invoice, the more time the insurer will take to review and scrutinize the bill. There are two issues here. First, a typical hospitalization is about 4-5 days long, so the hospital will invoice the patient’s insurer less than a week after the patient was admitted to the hospital. For COVID-19, on the other hand, it is not uncommon for patients to be hospitalized for 2-3 weeks. That means the hospitals are providing several weeks of treatment (and incurring the related costs) before they can submit an invoice to the insurer. Second, due to the long length of hospitalization and the expensive resources involved (e.g., ICU bed, ventilators, etc.) the invoices are very large, which means the insurers will spend a longer time reviewing the invoices before releasing payment. Both issues result in a substantial delay of payment which has a major impact on a hospital’s cash flow.

Bad Debt from Lapsed Policies – There are two basic types of private insurance – Fully-Insured and Self-Insured/Administrative Services Only (ASO) policies. With the Fully-Insured policies, an individual or employer pays a fixed premium to an insurer, who then assumes financial responsibility for all healthcare services provided to the insured individuals. With an ASO policy, the employer assumes financial responsibility, and will typically pay an insurer an access fee so the employees can use their provider networks, but the insurer does not have any of the financial responsibility for the claims themselves. Historically, ASO products were purchased by large companies that had the financial resources to manage uncertain health care expenses. For reasons that have been explored in other articles, the ACA (Obamacare) created a situation where smaller employers found ASO products to be attractive. As these employers find themselves unable to meet their obligations due to their own lost revenue from the shelter-in-place orders being implemented around the country, healthcare providers will find themselves not being reimbursed for a greater proportion of the care they provided right before the shut-downs than they are typically accustomed to.

Taken altogether, these factors paint a dire financial picture for hospitals and other healthcare providers over the coming months. We have already seen some hospitals furlough staff to manage these abrupt decreases in revenues, and others will surely face insolvency. Amid a global pandemic is the very worst time for hospitals and other providers to have to be dealing with such financial concerns.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) passed on March 25th partially addresses these concerns. Among other relief, it offers $100 billion for expenses directly related to responding to COVID-19, as well as a 20% increase in Medicare reimbursement to hospitals for COVID-19 inpatient admissions. While this will help providers with the extra costs COVID-19 will incur for them, it doesn’t do anything to address the sources of lost revenue detailed above.

In the long term, we may find transitioning away from the FFS model will grow increasingly attractive to providers. Capitation models, where providers are paid a fixed amount per patient regardless of how much care is provided, have long been known as an effective method for discouraging over-utilization. Providers have historically been skeptical of capitation models because there is a risk the payments will not be enough to provide all the services necessary to properly manage the care of their patients. This risk of insufficient capitation payment is not a concern in the FFS model. However, the capitation model does provide financial protection to providers by providing a steady stream of revenue during times when there is a significant drop in demand for medical services. There are numerous options to create hybrid models that take the best parts of FFS and capitation models to ensure a steady stream of revenue while incentivizing providers to reduce unnecessary services.

In the short-term, we need to ensure that healthcare providers are available to patients during the COVID-19 pandemic without worrying it will put them out of business or out of a job. This will likely require something over-and-above what is provided in the CARES Act, perhaps in conjunction with the nation’s health insurance companies. Once this pandemic is under control, we can then switch the conversation back to figuring out alternative payment models that will better manage the financial risks to providers and balance the down-side risks with the up-side rewards.

About the Author

Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.