Trend leveraging is an issue commonly overlooked when developing premium rates for new plan years. Trend leveraging occurs when rising healthcare costs result in more plan members surpassing deductibles or maximum out-of-pocket limits, increasing the financial burden on the plan sponsor. As a result, the plan sponsor is liable for a greater percentage of allowed claims than in previous years, and their “effective” trend is greater than the assumed claims trend. It is essential for plans to monitor this effect over time and take actions to mitigate its impact as desired.

Explanation of Trend Leveraging

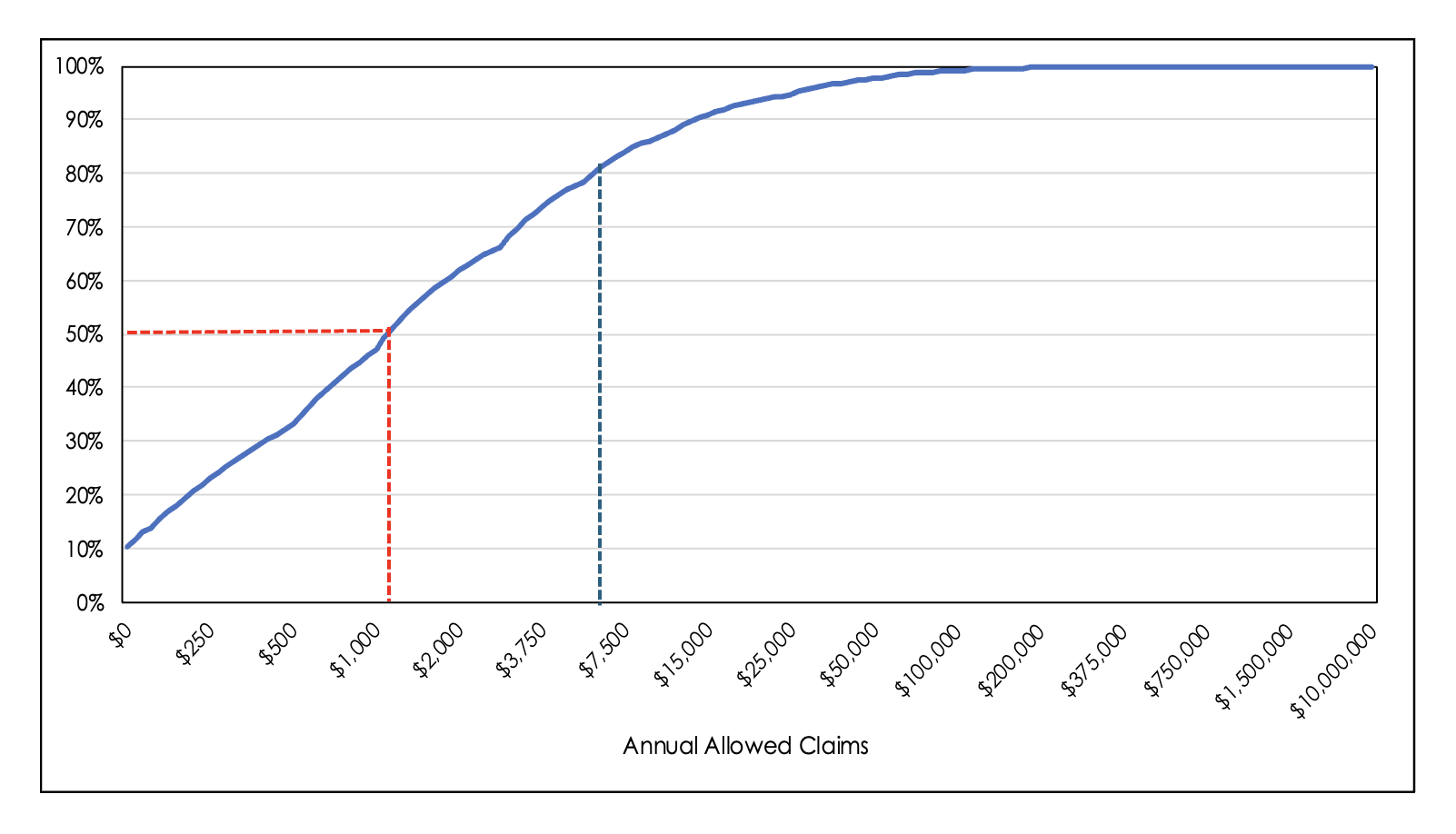

The causes of trend leveraging are rooted in an understanding of claims distribution. Exhibit 1 below shows a cumulative distribution function (CDF) for a population’s allowed claims. The median annual allowed claims is approximately $1,150, shown by the 50th percentile. This distribution is not to scale due to the significant skew from large claims. The average allowed claims shown by the blue dashed line is significantly higher than the median.

Exhibit 1: Claims Distribution Function for Example Population

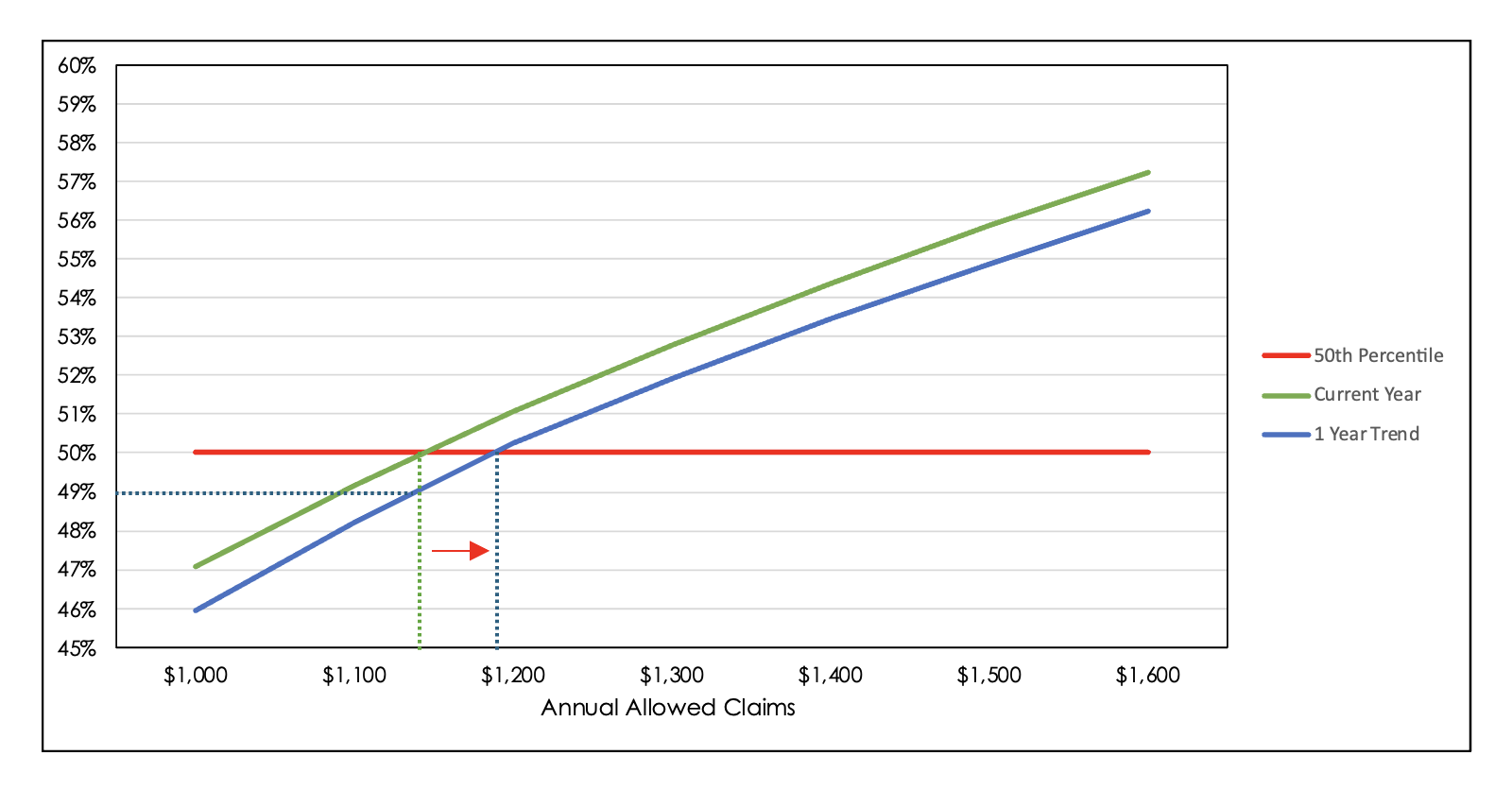

Applying an 8% cost trend will cause a subtle rightward shift in the CDF. Exhibit 2 shows the result of this trend and zoomed in around the 50th percentile. Although the shift is subtle, the median claims per member increases by approximately $50, from $1,150 to just under $1,200. In the current year, 50% of members had claims below $1,150. After one year of trend, only 49% of members have claims below $1,150 and 51% above it. Accordingly, there has been a 1% shift of members at the $1,150 threshold.

Exhibit 2: Claims Distribution Function Shift After Trend

Let’s assume a simple example of a plan with a deductible of $1,150 so that in the current year, half of the members would be expected to exceed the deductible. Assuming no other changes, after one year, we can expect 1% more members to exceed the deductible and benefit from the cost-sharing after the deductible. In the previous year, this same 1% of members were responsible for paying 100% of their claims, but the trend has now resulted in the insurer paying a percentage of those claims in accordance with the actuarial value and cost-sharing. Although the allowed claims increased by 8%, the sponsor’s costs increased by more than 8% to pay for the additional claims after the deductible.

The same dynamics occur for the out-of-pocket maximum, assuming it stays constant year-over-year. There are now more members who were previously in the cost-sharing zone but now exceed their out-of-pocket max. The plan sponsor is once again responsible for covering the difference.

How to Mitigate Trend Leveraging

A simple approach to offset the cost might be to increase the deductible and max out-of-pocket amounts by the same trend. However, when cost-sharing includes copays, this completely negates trend leveraging. Complications arise when modeling the utilization of various services before and after the deductible for a given population. Instead, a robust solution can be found with an actuarial value model that provides the expected percentage of claims costs paid by the plan sponsor versus the member. An effective model includes different cost-sharing inputs for a variety of services, preferably those listed on a typical Summary of Benefits & Coverage (SBC). Additionally, it should allow for CDF scaling caused by the year-over-year trend. These features will give the flexibility to combat trend leveraging by changing individual cost-sharing elements by varying degrees.

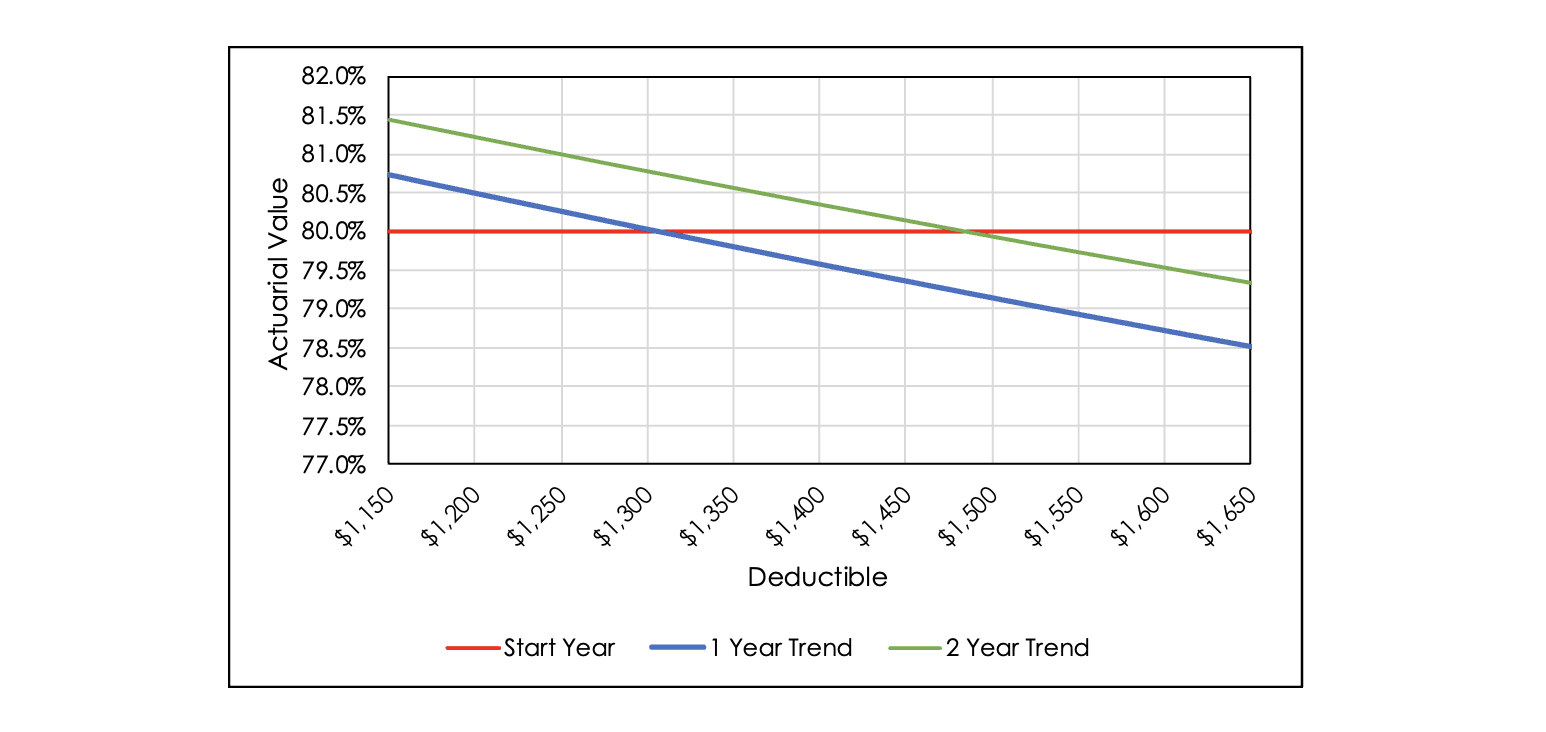

Expanding on the simplified example of a plan with a $1,150 deductible, we will need to make a few additional assumptions:

- Max out-of-pocket set at $8,230 which is aligned with the average gold plan for the 2024 individual market.

- All services are subject to the deductible with a 17.4% coinsurance, which yields a total plan actuarial value of 80.0%

Once again, assuming an 8% cost trend, Exhibit 3 shows the impact on actuarial value after 1 and 2 years. If the deductible remains unchanged, the plan’s actuarial value increases from 80.0% to 80.7% after 1 year and 81.4% after 2 years. To neutralize trend leveraging, the plan must decrease its cost-sharing benefits. Exhibit 3 also shows how trend leveraging can be mitigated by only changing the deductible. Increasing the deductible to $1,300 negates trend leveraging for a single year. Increasing the deductible to approximately $1,475 negates it for two years.

Exhibit 3: Actuarial Values for Varying Deductibles

The same exercise can be performed for a variety of cost sharing elements. Keeping the deductible constant, we can change the coinsurance assumption to also bring the actuarial value back to 80.0%. Exhibit 4 shows that coinsurance must increase to approximately 19.50% and 20.75% to mitigate trend leveraging for 1 and 2 years, respectively. This is an extremely simple example of cost sharing. Most plan designs include combinations of copays and coinsurances, with some services covered before the deductible. An actuarial value model will provide flexibility to alter these services individually to achieve the desired outcome.

Exhibit 4: Actuarial Values for Varying Coinsurance

When the actuarial value is maintained at 80.0%, the plan sponsor’s effective trend is kept equal to the cost trend (in this case, 8%). Every plan sponsor’s strategy will be different. Some sponsors might be willing to absorb the additional cost for the benefit of their members. Mitigating strategies can take place once every several years, annually, or never. If a long time has passed since changing a plan design, a more drastic measure might be necessary. With an actuarial value model, sponsors can decide which services are more appealing to decrease benefits for their members. Whatever the strategy, plan sponsors should be aware of trend leveraging’s impact on future claim costs when developing premium rates.

Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.

About the Author