Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.

Doing the Right Thing by Maximizing Quality

Introduction

This article is part of the Inspire series exploring accountability in key areas of today’s healthcare system. This article focuses on the accountability of physicians and other professional providers to “do the right thing” by maximizing quality. As described in the series overview, we have focused all the articles on what is known as the IHI Triple Aim.

In this article, the authors review the changing view of physician accountability and quality relative to each of the three Aims. This includes how quality is measured, how quality is used as incentive in physician reimbursement arrangements, and the resulting challenges and opportunities. We close with an informal rating of current provider accountability and offer some suggestions for next steps.

Accountability, Quality and “Doing the Right Thing”

Success in accountability requires knowledge of, and agreement to, what someone is being held accountable for. In this case it is useful to start by defining a few terms:

- Doing the right thing – According to Desmond Berghofer at the Institute for Ethical Leadership, this means to “make a choice among possibilities in favor of something the collective wisdom of humanity knows to be the way to act”.1 YourDictionary defines it more concisely as “to do what is ethical or just.”2

- Quality – The Oxford Dictionary3 defines quality as: The standard of something as measured against other things of a similar kind; the degree of excellence of something.

- Quality in Healthcare – In its report Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, the IOM (institute of Medicine) defines quality in healthcare as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge”.

- Accountability in Healthcare – For purposes of this article we will use a working definition of accountability in healthcare as “maximizing quality” in one or more of the three Aims.

Based upon our findings from the literature and interviews with active physicians, we conclude that some physicians may not agree with the last definition above. Their definition often, understandably and importantly, begins with “accountability to their patients”. For purposes of this article we define “Doing the right thing by maximizing quality” as taking actions in healthcare that optimize the outcomes of one or more element of the Triple Aim.

Measuring Quality

Success in maximizing quality in healthcare requires not only defining quality, but also measuring it. While it is important to know what quality in healthcare is, it is also useful to know what it isn’t. In healthcare, quantity is often confused with quality. In fact, overuse, underuse, and misuse are all indicators of poor quality in healthcare.

While quality measures may be independently developed, there are various organizations who develop and maintain quality measures (e.g., AHRQ, NCQA). Using professionally developed and maintained measures can provide a number advantages, including broader acceptance, greater range of measures to match specific provider needs, and ability to focus limited internal resources on developing and implementing improvement plans. Quality measurement was developed in some of the first managed care organizations who understand the significance of measuring the health of a population.

Before looking at a couple of examples, it is important to understand that some quality indicators used today do not truly measure outcomes of healthcare, but are proxies or process measures. These include the process measurement that are currently accepted such as percent of a female population with completed mammograms. While beyond the scope of this article, it is important to acknowledge the fact that no perfect system or set of measures exist for measuring quality of care. This is especially important when professional reputations and financial rewards are involved.

Following are two examples of broadly accepted organizational and physician/provider quality measures: The first is related to control of diabetes, the second is related to the overuse of antibiotics in treating adult sinusitis.

Example 1: Diabetes Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) Poor Control (>9%)

Measure Description: Percentage of patients 18-75 years of age with diabetes who had hemoglobin A1c > 9.0% during the measurement period

Quality Domain: Effective Clinical Care

Applicable Specialties:

- Internal Medicine

- Preventive Medicine

- General Practice/Family Practice

Primary Measure Steward: NCQA

The above measure provides a means of quantifying effectiveness of adult diabetic care, for a panel of diabetic patients using the ratio of patients with poor control (HbA1c > 9%) (numerator) to total panel (denominator). The results, when appropriately matched and compared to baseline or “best practice” results are often used as a proxy for measuring quality of care. Importantly, providing insights to where opportunities to maximize quality may exist. This is an example of an outcome measure; one that looks at the result or outcome (poor control of HbA1c) as opposed to a process measure (was a process performed), which is based on whether a procedure was performed.

Example 2: Adult Sinusitis – Antibiotic Prescribed for Adult Sinusitis (Overuse)

Measure description: Percentage of patients, aged 18 years and older, with a diagnosis of acute sinusitis who were prescribed an antibiotic within 10 days after onset of symptoms

Quality Domain: Efficiency and Cost Reduction

Applicable Specialties:

- Allergy/Immunology

- Internal Medicine

- Otolaryngology

General Practice/Family Medicine

Primary Measure Steward: American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery

The second measure is an example of a process measure. The focus is on identifying potential overuse of antibiotics in treating adults with sinusitis. Example 2 illustrates a potential for conflict of interest that occurs in many quality measurements. That is, the patient thinks what they need for their problem or complaint may or may not reflect best practice care. In this case an antibiotic for non-bacterial sinusitis. The physician/provider must always negotiate and educate the patient on what is best care. In most examples of this; the physician/provider knows that the patient does not need antibiotics and must convince the patient what is best care (i.e. no antibiotics). This is often a time-consuming process for the physician where the result of following best practice medicine may be an unhappy patient who receives no antibiotics. This is one of the pitfalls of some of the metrics.

Incentivizing Quality and MACRA

For illustrative purposes, we include an overview of one of the newer quality measurement systems being put into place in part due to the current focus on quality and emergence of CMS as a source of these measurements.

Traditionally physicians have often been reimbursed for their services on a fee-for-service basis (FFS). In effect, the provider charges a fee for each service (e.g., office visit, injection, test, etc.) delivered. A downside risk with the “do more, get more” FFS reimbursement approach is the over utilization of services and resulting excess cost. In recent years, various modified reimbursement approaches have emerged seeking to incentivize or reward desired physician behaviors, such as quality outcomes, patient experience, and management of per capita cost. These approaches tend to go collectively under the title “value based reimbursement” (VBR) or “pay for performance” (P4P). Common to each version, the provider’s (individual or group) performance is calculated based on a predefined set of measures and results used to adjust up or down reimbursement.

Recently CMS has begun implementing MACRA, (Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization ACT) a replacement to the historic SGR (Sustainable Growth Rate) method for determining increases in its Medicare Part B fee schedules. Its MIPS (Merit-based Incentive Payment System) represents a material shift by CMS away from traditional FFS reimbursement to a pay for value focus. Under MIPS, affected providers will receive a performance score based on the weighted results of their performances in each of four categories. This score will be used to adjust their future fee schedule payment up or down. Importantly all four categories (see Table 1) align in supporting the goals of the Triple Aim.

TABLE 1 – Performance Category Weights by Reward Year

| MIPS Performance Category | 2019 | 2020 | 2021+ |

| Quality of Care | 60% | 50% | 30% |

| Resource Use | 0% | 10% | 30% |

| Advancing Care Information | 25% | 25% | 25% |

| Clinical Practice Improvements | 15% | 15% | 15% |

The resulting weighted score (X) will be applied to the maximum bonus or penalty to determine a bonus or penalty adjustment to the standard fee schedule. See Table 2.

TABLE 2 – Maximum Bonus/Penalty by Year

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022+ |

| +/- 4% | +/- 5% | +/- 7% | +/- 9% |

When fully implemented in 2022, high performing providers could see a fee schedule difference of nearly 20% over low performers. (1 – (1.09/.91) =0.198 =19.8%). The Table 2 adjustments (plus and minus) are intended to be revenue neutral. That is, reductions from low performers will be used to fund the increases to high performers. Additionally, a $500 million fund has been budgeted to reward exceptional performers.

MACRA represents a step forward in several areas. For participants in the MIPS program, quality performance will be determined on a limited number of measures selected by the participant (see prior two examples). This will bring a level of simplification in terms of number of measures, as well as, the ability to align measures with current quality improvement efforts within an organization.

Based on the sheer number of lives covered by Medicare part B benefits (over 37 million as of 2015) any positive impact of MIPS on quality could be material. It also should be noted that traditionally what occurs in Medicare regarding reimbursement, measurements, etc. trickles down to Medicaid and Commercially insured populations.

Challenges and Opportunities

One of the current roadblocks to maximizing quality by providers is their concern, discomfort, and even anger at the rewards, incentives, and disincentives created by others to help them provide “better quality healthcare to their patients”.

On April 12, 2016 Donald Berwick defined medicine into 3 eras:

- Era 1-The ascendancy – dating back to ancient Greece where it was grounded in a belief that the profession had “special knowledge, inaccessibility to laity and would self-regulate. Researchers identified huge variation in practice, errors, profiteering and wasteful spending

- Era 2-The present – current backers believe in accountability, scrutiny, measurement, incentives and markets through manipulation of contingencies: rewards, punishments, and pay for performance. This has put the morale of the clinicians, healthcare managers in jeopardy as they feel misunderstood, and over controlled. Payers, consumers, and government feel suspicious, resisted, and helpless. This disconnect has caused both to dig in further and to some degree we are at an impasse.

- Era 3 – “the moral era” He suggests that this era will require updated beliefs rejecting the protectionism of era 1 and reductionism of era 2

He defines 9 needed changes:

- Reduced mandatory measurement

- Stop complex individual incentives

- Shift business strategy from revenue to quality

- Give up professional prerogative when it harms the team

- Use improvement science- plan, do, check, act

- Ensure complete transparency

- Protect civility

- Hear the voice of patients and families

- Rejecting greed

Our experience at AHP is consistent with what Berwick describes here and we will address a couple of his needed changes in the following description of Accountability and Triple Aim.

Accountability, Quality and The Triple Aim

As stated in the introduction, the focus of this article is the accountability of physicians and other professional providers for “doing the right thing” by maximizing quality. In this section we conclude with an informal assessment of physician accountability for maximizing quality in healthcare relative to the three components goals of the Triple Aim.

When we look at the provider community, and using the definition of accountability as “maximizing quality” by currently available metrics, we think that there is a long way to go, especially with accountability for per capita cost and population health.

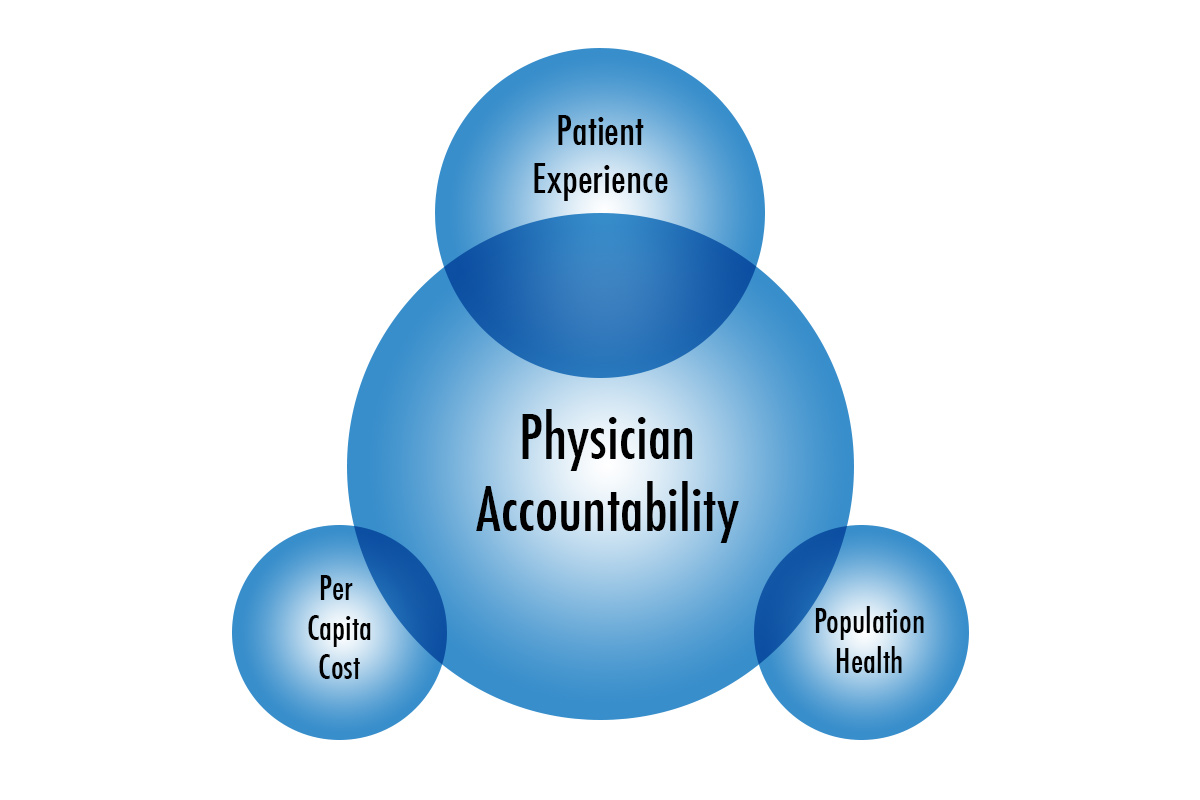

Diagram 1, is intended to illustrate this assessment: the primary alignment of physician accountability has been to the patient, with per capita cost and population health as marginal secondary accountability.

Diagram 1

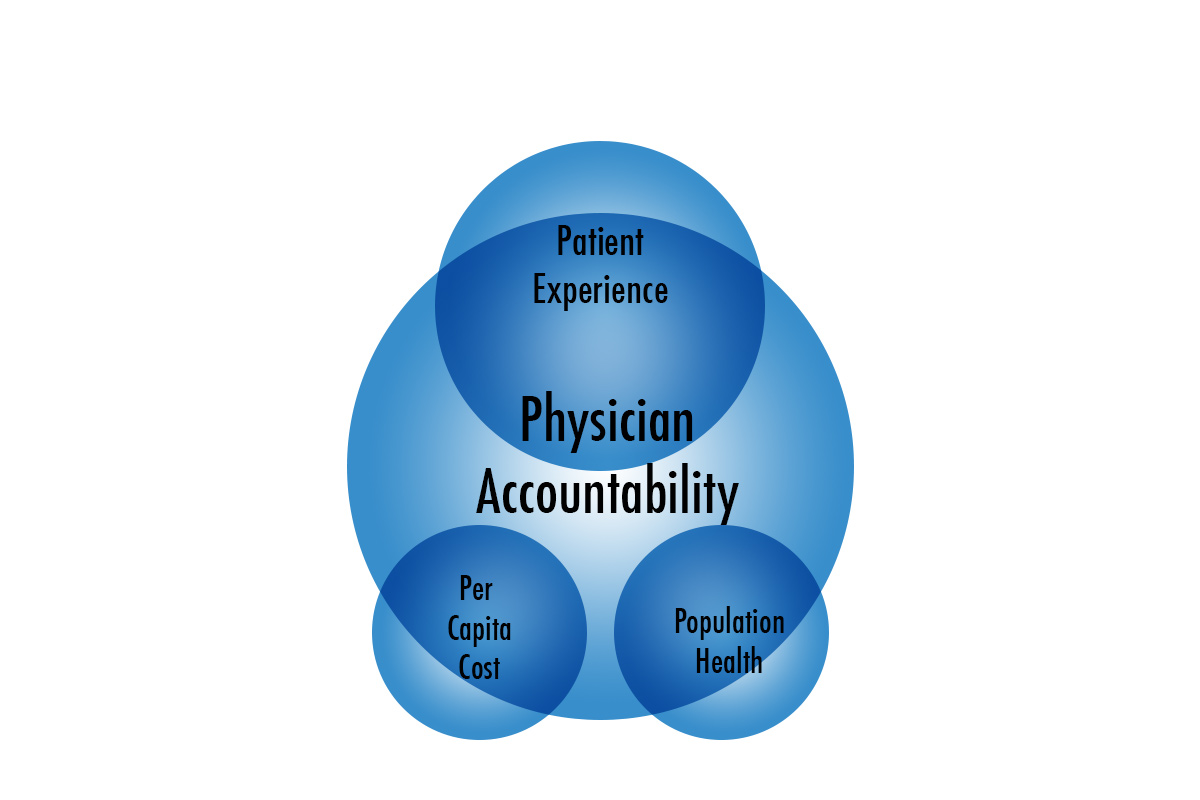

Diagram 2 illustrates the goal of a more accountable system where patient experience remains the primary accountability for physicians, but per capita cost and population health, while still secondary are more fully aligned with the physician’s overall accountability.

Diagram 2

It is our opinion that the key to moving toward diagram 2 is to gain provider buy-in. This will require many changes, such as the need to reduce the number of mandatory measurements, while also reducing the complexity of incentive payment arrangements. This may also require removal or simplification of certain physician accountabilities currently crowding out the components of the Triple Aim, (e.g., excessive paper work for insurance companies, ineffective tools for referring patients to highest quality/cost efficient providers, excessive data and measurements from payers to providers that are not actionable and different incentives from different payers).

The buy-in may also be dependent on the number of physicians/providers in healthcare systems, size of practices, as well as their time since graduation from medical school. The younger physicians are trained to be part of a team, transparent, to measure their performance, listen to patients, and families. This includes being comfortable with email and other telecommunications and other modern ways of communication.

We believe the Triple Aim objectives are a good set of values that is consistent with modern medical education and the way physicians/providers are currently educated.

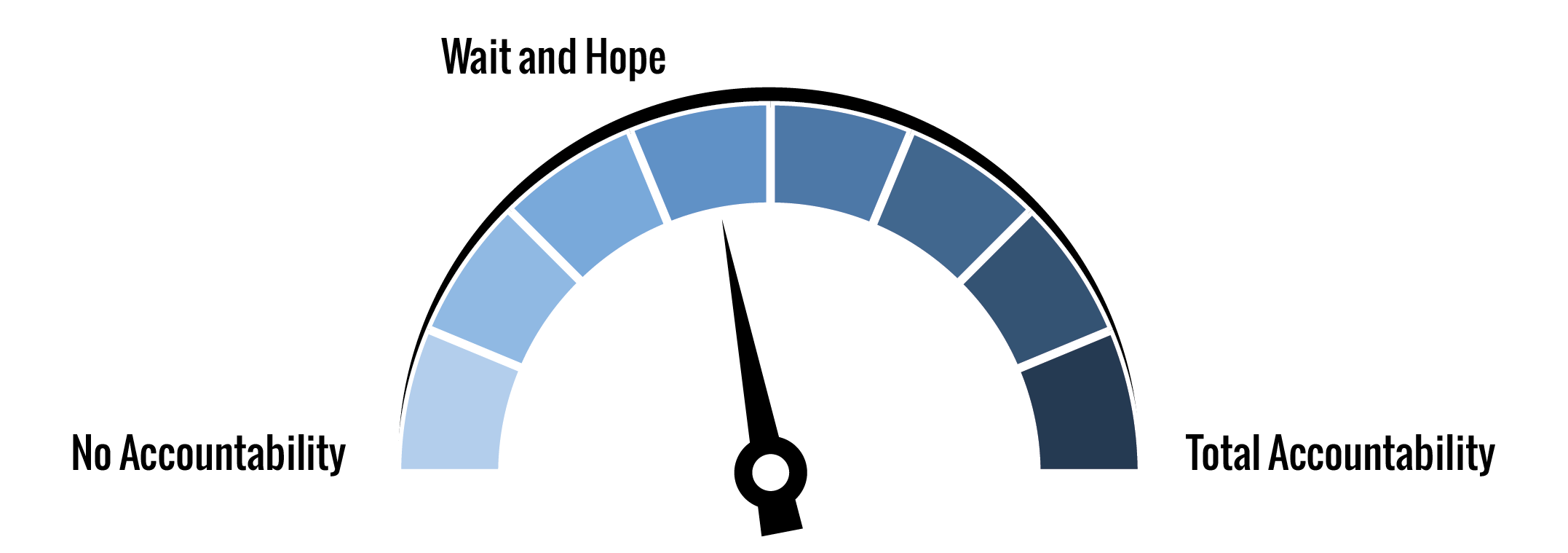

We think the current accountability by physician/providers (being maximizing quality by current available metrics) is only 40%.

We believe that the current metrics being used are only 40% of the way to maximizing quality.

We believe that the current incentive systems are much too complex and at most 30% of the way to maximizing quality.

Overall, we score physician accountability according to the Axene Accountability Index (AAI) as 40%. Physicians are held to a certain level accountability, but there is more that could be done to increase their accountability.

1www.ethicalleadership.com/DoingRightThing.htm, Desmond Berghofer , Institute for Ethical Leadership

2http://www.yourdictionary.com/do-the-right-thing#wiktionary, definition “to do the right thing” , Your Dictionary

3https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/quality, definition of quality, Oxford English Dictionary

About the Authors

Richard Liliedahl, MD, is the Chief Medical Officer of Axene Health Partners, LLC and is based in AHP’s Murrieta, CA office.

Oscar M. Lucas, ASA, FCA, MAAA, is a consulting actuary with Axene Health Partners, LLC and is based in AHP’s Seattle, WA office.