Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.

In 2004, the General Accounting Office changed its name to the Government Accountability Office (GAO). The name change was intended to alleviate confusion regarding the scope of services provided and to better reflect the mission of the agency. More subtly, it proudly acknowledged the fact that government itself is indeed accountable.

Today, the GAO is the government agency that analyzes the value of government division results relative to allocated taxpayer dollars. From a health care perspective, the GAO often weighs in on appropriate oversight of the Medicare and Medicaid programs.

While some aspects of government are self-monitored for accountability, the breadth of accountability requirements exceeds the metrics that can be objectively measured. An understanding of general accountability principles will enable government leaders to do their jobs more effectively and deliver appropriate services more confidently to citizens. The focus of this series is health care, and this article is focused in that arena, but the principles of government accountability hold true in all capacities.

As government1 continues to play a larger role in the health care economy, it is important for policy and regulatory leaders to understand appropriate accountability requirements. Government is unique and has a different perspective than private market entities that operate in the health care marketplace. Private health care requires a functioning business model. A private organization may have a missional goal but cannot function without revenue from a marketplace2 that supports that goal.

Government, on the other hand, receives revenue through taxation and seeks to spend money to fulfill determined purposes. There is often not a market or other frame of reference to benchmark government’s actions and performance. This could expose government to accountability lapses as competitive pressures are not present. For example, a physician group having challenges with one insurer could realign its business model with a comparable insurer while the same group could not change its contractual relationships to another government that provided the same services or funding.

Throughout this article, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) is used as an example to illustrate understandings of government accountability. The legislation was passed in 2010, and continues to be very visible and controversial. The significance of the legislation, which impacts all health care stakeholders, and the execution that followed provides good opportunities to illustrate damages caused by accountability lapses.

While the ACA is the example used throughout this article, government accountability applies to all areas where government touches the health care system. Experimentation with new value-based reimbursement models require transparency and adherence to government-communicated methodologies. The Medicare Access & CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) changes the way Medicare physicians are paid. Government is accountable for clearly communicating the new rules, and providing appropriate notice of future changes.

The sections that follow include important accountability requirements that are necessary for effective governing. As government moves forward with health reform, understanding and adhering to accountability requirements will facilitate optimal long-term solutions.

Appropriate Advice

Government leaders often bring different experiences and perspectives to their office. Members of Congress have traditionally been well versed in law; more recently, medical practitioners have sought public office and succeeded at the ballot box. As legislative responsibilities are all-encompassing, legislators will ultimately have to pass laws that are outside of their area of proficiency. This requires reliance on colleagues, staff or outside entities.

This raises an interesting and very important question. Who should advise government leaders on the complicated issues that are not in their scope of expertise? It’s safe to say that health care policy involving insurance markets is a relevant topic here.

There are more attorneys in Washington, DC than there are actuaries worldwide, and most of them earn a living by offering their opinions related to the impact of various policies. Of course, their paychecks often come from entities who have a financial interest in policy decisions. This creates somewhat of a dilemma; those with the best understanding of policy impacts usually have the largest conflict of interest.

While money from businesses always support informed views of policy impact, opinions on health care have been more abundant, and many academic professionals also weighed in on the ACA debate. As one would expect, not all opinions were accepted without question. Actuaries, generally known for providing dispassionate advice, released a report3 in 2013 warning of higher costs due to new rating requirements. While not used to being labeled as controversial, the report was dismissed by one senator who attached actuaries to the health insurance lobby4.

Ultimately, the market was designed to require a risk pool with a higher percentage of young adults than it actually achieved.5 Some commentators, without a complete technical understanding of the mechanics6, had argued that premium subsidies would attract young men to the market and achieve the desired risk mix. There is now acknowledgment that “the ACA has some problems but can be fixed” but little consensus on the underlying structural problems. A member of Congress recently remarked that allowing insurers to vary rates by age (and other rating factors) is wasteful and not cost-effective. With one of the major challenges of the risk pool already being an unbalanced age mix, comments suggest that bad advice is still easy to find.

How does government determine what is “appropriate advice”? One beneficial insight is the understanding is that real solutions are not divisive and segmented. In the health policy arena, many unfortunate opinions are of the mindset of consumers vs. insurers, or physicians vs. patients, or “big pharma” vs. everyone. Functioning markets require mutual benefit for buyers and sellers. Advice that suggests deliberate harm to one party as part of a solution is likely to be implemented ineffectively and not well received, and should be avoided.

One other effective tool is actually an often-overlooked requirement in the actual analysis of health policy design. Health policy considerations should include considerations of health care stakeholder incentives; likewise, government should understand the incentives of who is providing policy advice. If one has a preconceived policy goal, it’s easy to find data to support that position. Actuaries have broad responsibilities to be objective and impartial, and possess the technical expertise to provide a full and complete analysis.7

The Importance of Consensus

When businesses engage in transactions, it is generally assumed that each party will abide to certain behavior once an agreement is reached. Over time, employee turnover occurs but new employees often are hired to continue the business model. The owner of a business does not usually hire someone who has goals and ideals incompatible with his own.

Government has been known to operate differently. Government representatives are often elected by citizens as opposed to being selected by someone already in government. This often leads to different views and different missions. Elected officials may represent constituents with different views and have different perceptions about what they are elected to do.

Major legislation that lacks consensus often presents execution challenges. The ACA was passed by the narrowest of margins. In fact, the replacement of a US Senator changed the political makeup in the Senate, and the House of Representatives accepted the Senate bill without modification to avoid the Senate having to vote again. Many “drafting errors”, which would normally be resolved through a conference committee, remained in the final legislation. Due to a lack of continued lack of consensus, many issues (that virtually everyone acknowledges are real problems) remain unresolved.

One example is the so-called “family glitch”. Individuals with access to affordable employer-sponsored coverage are not eligible for premium and cost-sharing subsidies. The ‘affordable’ definition is based on the required premium contribution relative to the employee’s household income. The affordability test is based on employee-only coverage and not family coverage. This results in some families not having affordable employer-sponsored coverage and also not being eligible for premium and cost-sharing subsidies.

The current attention over reimbursements for Cost Sharing Reductions (CSR)8 highlights another downfall of lack of consensus. The ACA requires insurers to reduce cost-sharing for certain low income enrollees with the expectation that the costs will be passed through to the government. At the same time, Congress never formally appropriated these funds but they were paid by the Obama administration. Legal challenges followed, and President Trump entered office with somewhat of a dilemma – to either continue making the CSRs payments which contracted insurers were expecting or stop the payments and risk insurers exiting the market and potential lawsuits. Legal predicaments such as these rarely occur with consensus legislation.

Know The Legal Limits

It goes without saying that legislative bodies should only pass laws that are legal. As almost all legislation provokes perceived harm for some groups or some people, any questionable elements of a law could be challenged in court. The likelihood of a legal challenge is also related to the magnitude of the law and a lack of consensus. A contentious bill that has significant impact to certain stakeholders is more likely to be challenged.

There have been numerous lawsuits associated with the ACA. Many have revolved around the implementation of some of the regulatory rules. A case challenging the constitutional fidelity of the law was elevated to the US Supreme Court and had mixed results. Legislation that lack a legal stable foothold also creates uncertainty in the market and may repel participants. As legislators debate significant issues that lack appropriate consensus, they should be intensely sensitive to potential legal challenges.

Reliable Business Partner

The business of health insurance and the associated regulatory requirements necessitate significant lead time for developing premium rates before they become effective. Premium rates are generally effective for one year, and cannot be changed mid-year due to unanticipated developments.

The pricing of health insurance is complicated and technical, and relies on many factors. Actuaries are well aware of the necessary considerations, but government leaders could logically be insensitive to potentially inflicting market damage. With the ACA, many rules have not been enforced or have subsequently been changed, often “through the use of executive decisions, waivers, and deadline extensions.”9 The allowance of transitional (or grandmothered) plans were not anticipated by insurers, which would have resulted in higher premiums to reflect healthier individuals delaying migration into ACA markets. Businesses will not continue to participate in markets where they cannot rely on their partners to keep their promises.

In summary, as government plays a larger role in the health care economy, it must be an accountable and trusted business partner.

Transfer of Responsibility

When government passes laws that transfer responsibilities to government from private enterprises, government becomes accountable for those results. Rating restrictions are a common limitation that government imposes on insurance companies.

Prior to the ACA, insurers would develop rates for small employers based on the characteristics of the employees. Insurers typically had flexibility to develop rating factors based on actuarial data. If an insurer applied inappropriate factors, it would likely result in negative enrollment and financial results. In this scenario, the insurer would have no justification to shift blame as it had control over the applied factors. If it recognized the problem, it would update its factors to improve results in following years.

With the ACA, government removed some of the rating flexibility for insurers. Rates could no long vary by gender and health status, age rating was compressed and factors developed by the government were mandated. In a sense, the government took ownership of the rating factors. As the new factors were not actuarially appropriate, government implemented a risk adjustment system to actuarially reconcile the limited factors. Insurers had to live by the government’s assumptions and apply factors that they previously developed internally. It is fair to say that they were formerly responsible for the accuracy of their own estimates. With the ACA, that responsibility now lies with government and is out of the control of insurers; insurers are justified in demanding that the government factors and associated adjustments are correct.

I highlight the risk adjustment example with the knowledge of ongoing challenges10 and charges of inequities in the methodology. Without going into technical details11 in this article, the government agreed to accept a major challenge to develop an equitable budget-neutral program. In March 2016, the government released a Discussion Paper12 highlighting potential changes to the risk adjustment model based on industry feedback. Some of the characteristics of the methodology posed unique challenges on the CO-OPs, organization that were catalyzed by ACA funding. Most of these organizations have since become financially insolvent and have ceased operations.

As insurers are not able to select risks or price accordingly for the risk received, they must rely on government methodology for an appropriate and adequate financial accommodation. It is imperative that the operational methodology is therefore precise and impartial, and accurately transfer risk payments and not be influenced by other factors.

The intent of this section is not to cast blame on government for the failure of certain companies, but to highlight the enormous accountability and risk that government assumes when it transfers private market decisions to government agencies.

Unintended Consequences

They are likely drinking more beer in the City of Brotherly Love these days. It is not related to the Phillies being last in their division (they are) and it has nothing to do with the weather. It’s the soda tax. The tax on soda products, intended to raise revenue,13 has resulted in prices higher than the cost of beer, and presumably shifted consumption patterns, generating far less revenue than expected.

Legislation that involves tax policy often has an intention to either raise revenue or change behavior. Often, the results include a mixture of both outcomes, and usually some unintended and unexpected effects.

The ACA included a litany of tax subsidies and mandates that resulted in tax penalties for non-compliance. Measuring the isolated impact of each one is subjective but the directional impacts of each are trivial. Individual subsidies and mandates will have upward impact on enrollment patterns. Subsidies that decrease with income will discourage work to some extent. Mandates that apply to employers based on number of employees and hours worked will impact hiring patterns and work schedules.

Unbiased technical expertise is needed to model the impact of such changes. Unlike the Medicare and Medicaid programs, the free market element of purchasing insurance coverage without significant financial assistance14 is much more challenging to project.

With traditional government programs, funding is often the primary lever to consider. When regulating and subsidizing insurance markets, accountable government requires utilization of appropriate expertise that is likely outside of the traditional government sources.

The Buck Stops Here

President Harry Truman is well known for having a small sign on his desk reminding anyone who may be in his office (and himself) that “The Buck Stops Here”. The phrase is derived from the slang expression “pass the buck” which means to defer one’s responsibility to someone else. “The Buck Stops Here” signifies where decisions are made and where responsibility lies. As government takes ownership of decisions previous held by private enterprises, it accepts new responsibilities.

If government action creates new problems, it seems evident that government should be responsible for necessary corrections. There have been numerous instances with the ACA where government has attempted to “pass the buck.” Most notably, insurer participation has diminished since 2015 and various geographic markets have been unattractive and in danger of not having any participating carriers. Government leaders have sometimes suggested that insurers who operate in other markets should be forced to participate in the individual market regardless of financial outlook. This ignores both general principles of actuarial soundness and rules that disallow other government programs to subsidize losses in other lines of business. At a recent hearing, a senator told an insurance company witness that his company was “holding a knife to their own throat”15 by not participating in counties where there were no other insurers, creating “incredible pressure for us to provide a solution”.16

For health insurance to function effectively, each line of business should be self-sustaining. Insurance principles and various regulations require this. If government enforces new rules on a market, government is accountable for the impact of those rules.

It is troubling to hear government over promise market success, and then react to failure by mandating participation for some insurers. Insurers have different characteristics: some are specialized to serve the Medicare market, others may have invested significantly in developing a network with limited geographical breadth, and some markets/area may not make sense for their business model. Required insurer participation in new markets or geographic areas would have inequitable effects on various insurers and change profitability requirements in other lines of business and create competitive disadvantages. In a sense, it is also a soft admission of government failure. If government is going to craft market solutions, government is accountable for functioning markets, which includes attracting suppliers. Requiring participation of insurers to substitute for government accountability is untenable.

Any effort by government to significantly redesign markets will likely have positive and negative impacts, some expected and some unexpected. A natural tendency for government may be to accept the benefit of the positive changes and cast the accountability of the negative impact on market players. Government should have a “Buck Stops Here” attitude with regard to both desired and unintended outcomes. A recognition of this accountability is a catalyst for designing markets that are attractive to both buyers and sellers.

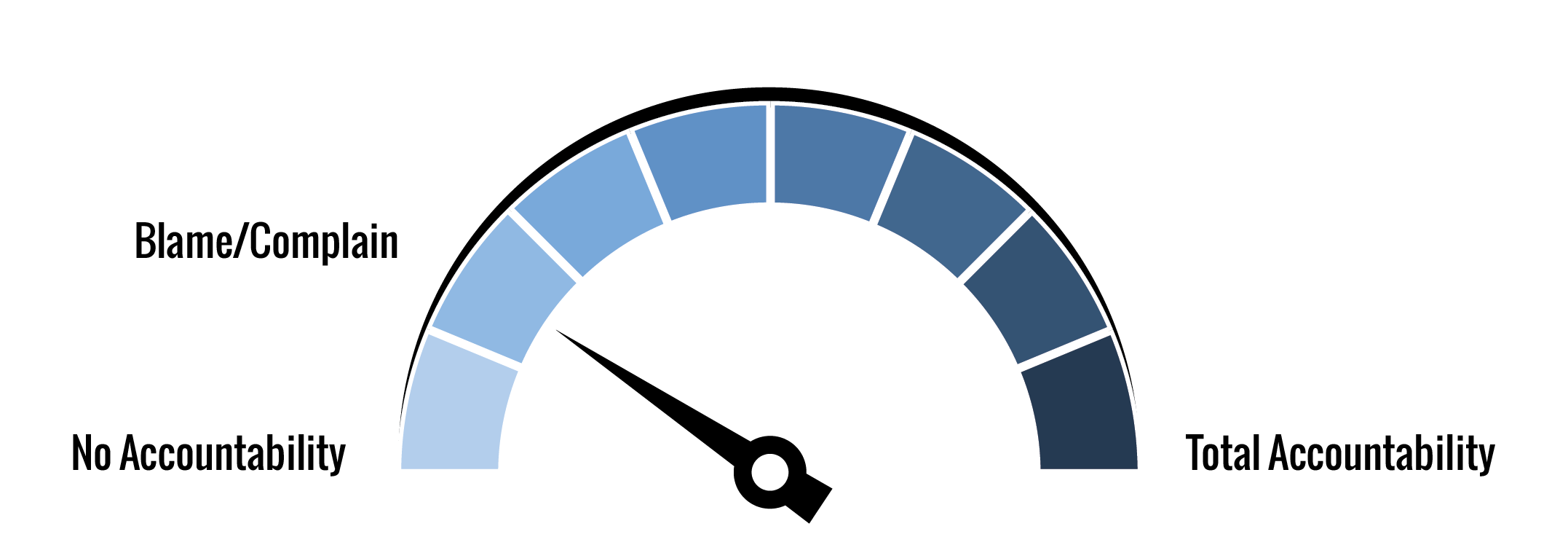

AHP Accountability IndexTM (AAI) and Government

Rating government accountability is a subjective process. The Triple Aim aspects (patient experience, population health, cost of care) were formally implemented in the government structure when one of the founders of the framework accepted a leadership role in the Obama administration. The scope of government’s role in the health care system is massive and all stakeholders would likely have biased views based on their own limited government interactions. Consistent with the theme of this article, the Index estimates are based on the author’s opinions of ACA markets, which have been the most impacted by government’s actions in this decade.

Patient experience is largely poor. The shift to government-sponsored exchanges from traditional distribution channels was supposed to foster a competitive environment with smooth transactions. The early implementation was largely regarded as an operational failure and competition is sparse in many areas. Actual enrollment in individual markets is about half of what was expected. The market rules impacting premium rates and the associated government subsidies reduced the costs for lower-income individuals but increased the costs for many others. With the amount of government funding allocated to the ACA, better results should have been achieved.

Population health is mixed. The ACA has been an impetus for more awareness of the need of health insurance. It cannot be ignored that the benefit of having insurance also provides incentives for unnecessary care. The appropriateness of the increased use of opioid for newly-insured individuals is a major concern.

One of the early promises of the ACA was reduced costs. It’s a fairly universal view that the ACA has resulted in more people being insured, but has done nothing to control costs. In fact, it’s hard to hear a debate on ACA that doesn’t get distracted by a “health care costs (rather than insurance premiums) are the real problem” argument.

With those considerations in mind, the following chart summarizes a government assessment of AAI.

| Triple Aim Category | Weight | Rating |

| Patient Experience | 0.333 | 20.0% |

| Population Health | 0.333 | 50.0% |

| Cost of Care | 0.334 | 0.0% |

| Overall | 1.000 | 23.3% |

Conclusion

It is important for government leaders to understand the appropriate role of government and accountability requirements. A free market economy requires attractive options for buyers and sellers. Government can play a positive role, but ambitious well-intended government policy often fosters unintended consequences. Regulation of insurance markets is challenging, and appropriate unbiased expert advice is crucial.

The lesson learned from the ACA experience include the need for appropriate advice, an understanding of incentives, the importance of consensus, the need to be a reliable business partner, and the acceptance of accountability. Adherence to these principles will foster good policy and a competitive market that attracts buyers and sellers. The health care system will flourish when appropriate accountability is implemented for public as well as private market participants.

1The term “government” is used generally to represent various governmental entities. The purpose of this article is to demonstrate the unique accountability of government agencies. A particular agency or political party affiliation is often inconsequential (and perhaps distracting) to understand the larger point.

2While health care in the U.S. is delivered through private businesses, there is an element of charitable dollars used to fund hospital construction, care, and other missional activities.

3http://cdn-files.soa.org/web/research-cost-aca-report.pdf

4https://hotair.com/headlines/archives/2013/04/health-actuaries-obamacare-rates-are-going-to-soar/

5http://www.theactuarymagazine.org/the-true-cost-of-coverage/

6https://www.soa.org/Library/Newsletters/In-Public-Interest/2016/september/ipi-2016-iss13-fann.aspx

7https://www.soa.org/Library/Newsletters/The-Actuary-Magazine/2015/june/act-2015-vol12-iss3-tofc.aspx

8https://axenehp.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/ahp_inspire_20170809.pdf

9http://www.washingtonexaminer.com/how-obama-knee-capped-his-own-health-reform/article/2635220

10https://www.bizjournals.com/albuquerque/news/2016/08/01/nm-health-connections-files-lawsuit-against-feds.html

11https://minutemanhealth.org/MinutemanHealth/media/Outreach%20and%20Comms/Oct2016/Comment%20Letter%20Appendix%20I_Part1.pdf

12https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Forms-Reports-and-Other-Resources/Downloads/RA-March-31-White-Paper-032416.pdf

13https://townhall.com/tipsheet/mattvespa/2017/08/10/disaster-phillys-soda-tax-has-produced-miserable-results-n2366836

14https://stateofreform.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/AHP-Inspire-Free-Market.pdf

15http://www.thinkadvisor.com/2017/09/14/insurers-are-holding-a-knife-to-their-own-throat-k?slreturn=1506638522

16http://www.thinkadvisor.com/2017/09/14/insurers-are-holding-a-knife-to-their-own-throat-k?slreturn=1506638522

About the Author

Greg Fann, FSA, FCA, MAAA, is a Senior Consulting Actuary with Axene Health Partners, LLC and is based in AHP’s Murrieta, CA office.