Healthcare Affordability in the United States

Addressing the high cost of healthcare in the U.S. is a complex issue that requires a multifaceted approach, including measures to improve efficiency, reduce administrative costs, increase price transparency, and promote preventive care and healthy lifestyles. High costs are often talked about in the market, but affordability is often not part of the conversation. The affordability of healthcare varies widely across the United States, and this report will attempt to quantify that.

Healthcare cost and healthcare affordability are related concepts but differ in their focus and implications:

- Healthcare Cost: Healthcare cost refers to the actual amount of money spent on healthcare services, including medical treatments, procedures, medications, hospital stays, doctor visits, and other healthcare-related expenses. This includes both the expenses incurred by individuals or families and the expenditures of healthcare providers, insurers, and government healthcare programs.

- Healthcare Affordability: Healthcare affordability, on the other hand, refers to the ability of individuals, families, or populations to pay for healthcare services without experiencing financial hardship or sacrificing other essential needs. Affordability takes into account not only the absolute cost of healthcare but also the income levels, financial resources, and insurance coverage of individuals or families.

While healthcare cost primarily focuses on the monetary value of healthcare services, healthcare affordability considers whether these costs are manageable and equitable for individuals or communities. For example, even if healthcare costs are high in a particular region or country, if the majority of the population can afford these costs without significant financial strain, then healthcare in that region may be considered relatively affordable within that context.

“The Triple Aim (quality improvement, population health improvement, and cost reduction) can be used as a framework to develop and evaluate healthcare initiatives.”

Conversely, even if healthcare costs are relatively low, if a significant portion of the population cannot afford necessary medical care due to low income, lack of insurance coverage, or high out-of-pocket expenses, then healthcare may be deemed unaffordable for those individuals or communities.

Addressing healthcare affordability involves not only controlling healthcare costs but also implementing policies and programs to ensure that healthcare services are accessible and affordable for all individuals, regardless of their socioeconomic status. This may include measures to expand health insurance coverage, reduce out-of-pocket expenses, increase access to preventive care, promote price transparency, and address social determinants of health that impact individuals’ ability to access and afford healthcare services.

This report focuses on healthcare affordability in terms of the AHP Healthcare Affordability IndexTM or AHP HCAITM, a proprietary tool of Axene Health Partners, LLC, and updates earlier versions of this analysis.

Healthcare industry stakeholders are generally familiar with the Triple Aim of Healthcare developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The Triple Aim (quality improvement, population health improvement, and cost reduction) can be used as a framework to develop and evaluate healthcare initiatives. Codified into this framework is the importance of cost; it is well understood that cost-effectiveness must play a role in any viable solution (at least in the long term).

But cost does not exist in a vacuum. Someone is paying the high cost of healthcare. Thus, it is not just the cost of care that matters, but rather, the affordability of that care: the cost of care in relation to available resources. Assessing affordability necessitates consideration of both cost and the ability to pay.

Though the term “affordability” has been a primary feature of the public discourse on the American Healthcare system in recent years (particularly surrounding discussion of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) of 2010), the focus on cost has often overshadowed the conversation about ability to pay. The intent of this report is to highlight both sides of affordability and to recognize the financial burden on the payer or purchaser of healthcare services.

AHP Healthcare Affordability IndexTM

The AHP Healthcare Affordability IndexTM was developed to measure and evaluate the relative Healthcare affordability for key stakeholders across various geographic regions. For each stakeholder within a region, we calculate the ratio of estimated Healthcare costs to the stakeholder’s annual income or resources available to pay for their portion of the Healthcare costs. We then develop the AHP HCAITM for each stakeholder by normalizing the result to a standard affordability level so that we can compare the relative affordability of each region by stakeholder.

For purposes of this study, we have calculated the AHP HCAITM for the three major purchasers of healthcare: employers, employees, and the government. We have additionally created a Private Payer AHP HCAITM by combining the employer and employee perspectives, as well as a National AHP HCAITM by combining all three perspectives. Our findings are presented in the discussion below.

Given that the AHP HCAITM is calculated as a ratio of costs to income, a region with a lower AHP HCAITM is interpreted to be more affordable than one with a higher AHP HCAITM. In other words, the lower the AHP HCAITM, the more affordable healthcare is in that region or jurisdiction.

Employer HCAITM

The Employer HCAITM is intended to demonstrate relative healthcare affordability for employers by region or jurisdiction. This index is calculated as the ratio of employer-paid healthcare costs to employer income, which is defined for purposes of this paper as the state GDP. The methodology used to estimate employer healthcare costs and state GPD for input into the Employer HCAITM formula is described in the next paragraph.

Employer healthcare contributions were estimated using the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) Insurance Component. State GDP was calculated using data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

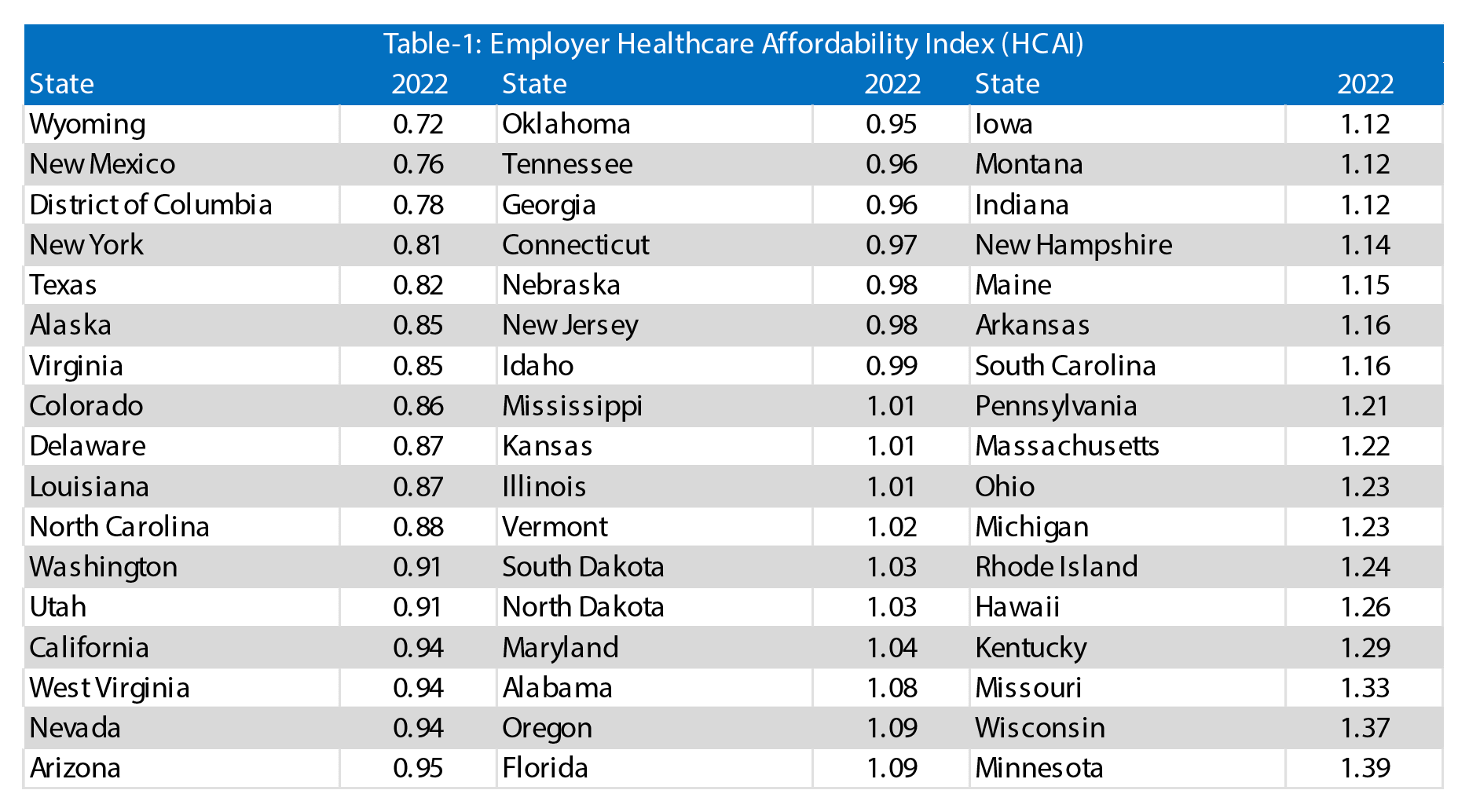

The 2022 Employer HCAITM is shown in Table 1 below, organized from most affordable to least affordable:

The graphical depiction of the 2022 Employer HCAITM in Figure 1 illustrates that the least affordable regions are concentrated primarily in the Midwest and Southern regions of the United States, while the most affordable states are located in the West and the Northeast.

The more affordable areas tend to have relatively high state GDP per employee; enough so that the impact of the higher Healthcare costs in these states is offset by higher revenues. For example, New York in recent years was among the top five jurisdictions for highest average expenditures per employee, but also was always in the top five for highest state GDP per employee. For similar coastal states, Healthcare appears to be more affordable despite the higher cost because more resources are available. In addition, in those states where the Healthcare cost allocation between employer and employee is biased towards the employer, a higher relative Employer HCAITM may occur. One example of this might be states with higher levels of labor-negotiated contracts or the willingness or ability of employers to pay a greater than normal portion of their employee’s Healthcare costs.

Figure 1: Employer HCAITM by Jurisdiction for 2022

Using the historical scores for the Employer HCAITM found in the appendix, we find that the standard deviation of the Employer HCAITM has been holding steady since 2013 with a sudden sharp uptick in 2018. Both the minimum and maximum Employer HCAITM increased in 2021, and the minimum Employer HCAITM still remains above 2020 levels in 2022. This indicates that since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, no state has experienced unusually improved relative employer affordability, but some states (like Kentucky, Missouri, and Minnesota) have experienced some significant relative employer lack of affordability.

Employee HCAITM

Less than 10% of the U.S. population has Healthcare insurance coverage through the individual market, while about 50% of the population is covered through their employer. Given this discrepancy, we will focus on affordability for those enrolled in employer-sponsored group coverage in this section, although the topic of affordability on the individual market is an interesting one and could be the subject of a follow-up report.

The Employee HCAITM is calculated as employee Healthcare costs divided by employee income. Employee Healthcare costs include premiums, deductibles, coinsurance, and copays, as well as out-of-pocket payments for items or services that are not covered by insurance. The methodology and data sources used to estimate each of these for input into the Employee HCAITM formula are described in the next paragraph.

Premium costs were estimated using the MEPS Insurance Component, while non-premium out-of-pocket costs were estimated using the MEPS Household Component. Salaries were estimated using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The Employee HCAITM for 2021 is shown in Table 2 below, organized from most affordable jurisdiction to least affordable:

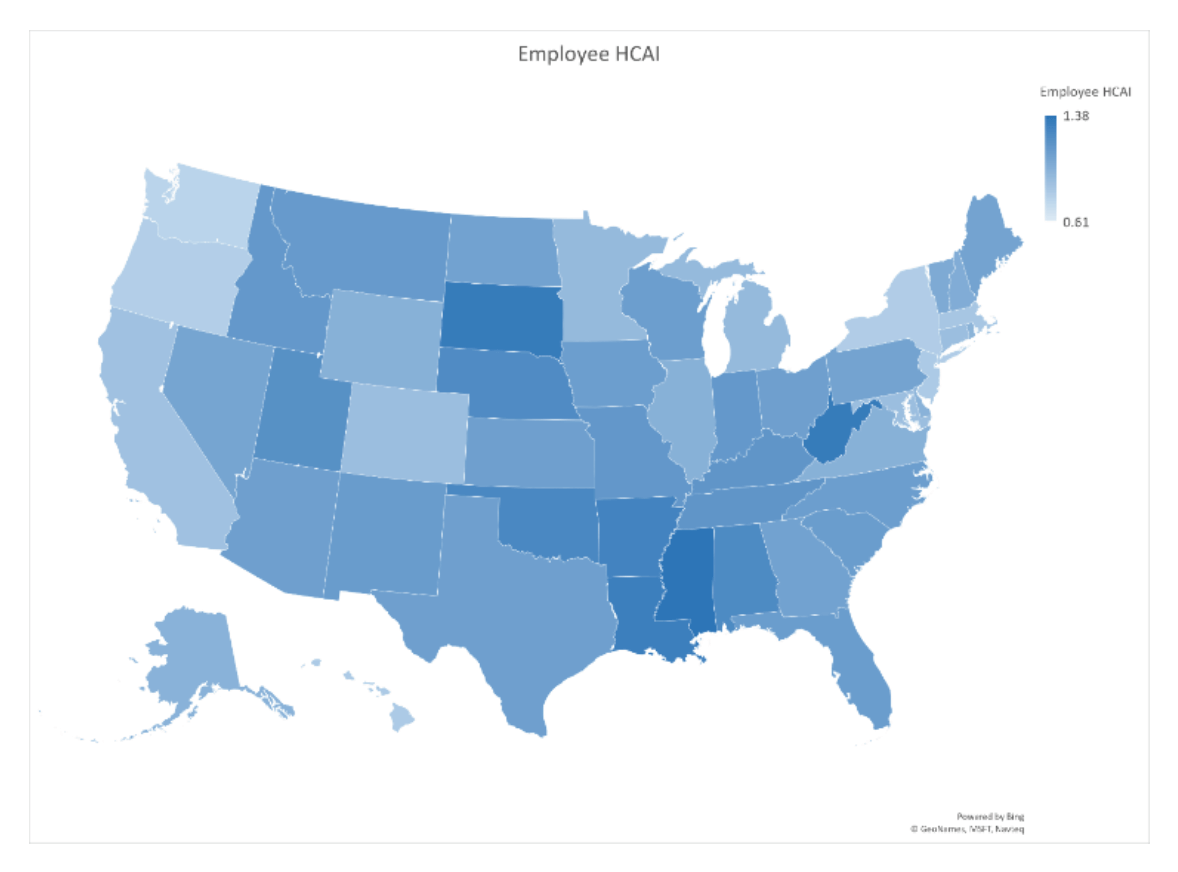

The graphical depiction of the Employee HCAITM in Figure 2 below illustrates that the least affordable regions are concentrated in the southeast and Midwest regions of the United States, while the most affordable states are located in the west and northeast. Though it may seem counterintuitive that some of the most affordable states are also states with notoriously high cost of living (i.e., California, New York, and the D.C./Maryland region), these are also states with higher than average incomes. The high average incomes result in healthcare expenditures comprising a lower percentage of income so that healthcare is relatively more affordable in these states. This finding comes with an obvious caveat about income inequality, particularly for very populous and diverse states like California. A lower Employee HCAITM in aggregate does not preclude the existence of pockets of very unaffordable regions on a more local level.

Figure 2: Employee HCAITM by Jurisdiction for 2021

The HCAITM history for employees is found in the appendix. The state with the largest improvement in affordability over the last decade was Minnesota, while the state with the worst deterioration in affordability was Pennsylvania. The District of Columbia has been the most affordable every year, while Hawaii and Washington were in the top five each year for the last ten years. Overall, nine unique states have made it into the top five most affordable.

“The state with the largest improvement in affordability over the last decade was Minnesota, while the state with the worst deterioration in affordability was Pennsylvania.”

The rankings of the five least affordable states had more turnover: while South Dakota has been among the five least affordable every year, it has only been the least affordable eight of those times. No other state has made it into the bottom five every year, although Mississippi and Louisiana have ranked that low eight of the last ten years. Overall, 16 unique states have been in the yearly five least affordable states.

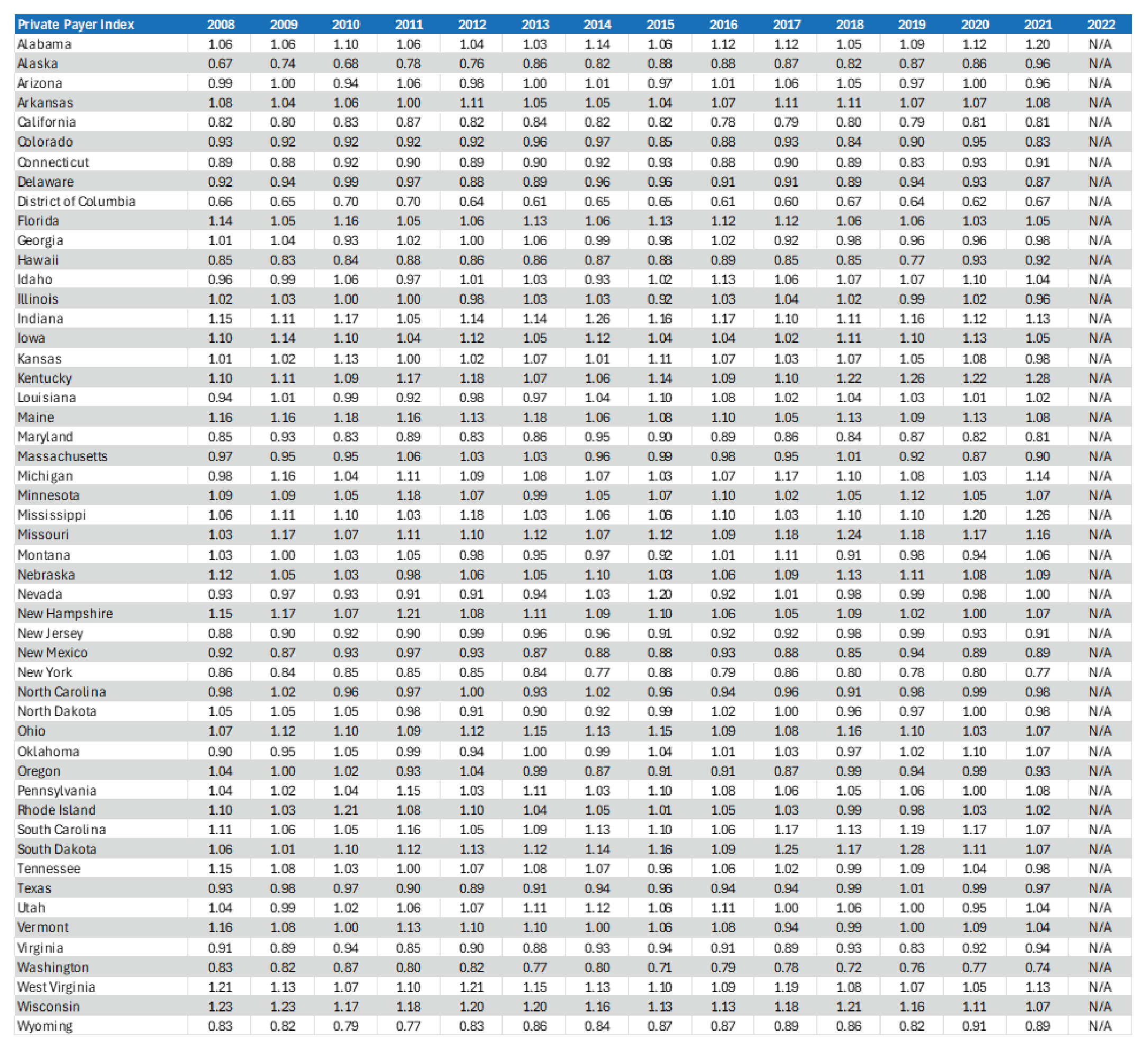

Private Payer HCAITM

We have combined the Employee HCAITM with the Employer HCAITM to create the Private Payer HCAITM. The results are summarized in Table 3 below:

The graphical description of Private Payer HCAITM shown below in Figure 3 demonstrates that, as expected, the Midwest and Southeast regions are the least affordable for employees and employers combined, while the West and coastal regions have more favorable indices.

Figure 3: Private Payer HCAITM by Jurisdiction for 2021

The full history of the Private Payer HCAITM is found in the appendix. Similar employer and employee indexes. It can be seen that very few states tend to experience dramatic change in their HCAITM over time.

Government HCAITM

The final payer that we will consider is the government. Both the federal and state governments act as payers: Medicaid and CHIP have both federal and state funding sources, while Medicare is funded on a federal level. Federal and state governments also act as employers and so fund some of their employees’ share of Healthcare premiums, in addition to funding other Healthcare activities and programs such as subsidies on the PPACA exchanges and Healthcare coverage for active-duty military, their families, and veterans. Since the non-employer, non-Medicare/Medicaid pieces comprise the minority of total government Healthcare expenditures (less than a fifth), we will focus on Medicaid, CHIP, and Medicare for purposes of this analysis.

The Government HCAITM is calculated as state and federal Healthcare costs divided by government income. Government income includes taxes as well as premiums paid for Medicare Part B and Part D. The methodology used to estimate both costs and income for purposes of computing the Government HCAITM is described in the next paragraph.

Medicaid and CHIP expenditures were taken from the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). Medicare expenditures were estimated using historical National Health Expenditure data and the Medicare Enrollment Dashboard File. Medicare enrollee premiums for Part B and Part D were estimated using the Medicare Enrollment Dashboard File along with data accompanying the Medicare Trustees Report. Federal tax income was sourced from the IRS, while state tax income data is from the United States Census Bureau.

The Government HCAITM for 2021 is shown in Table 4 below, organized from most affordable to least affordable:

As in our most recent report, the least affordable states are Mississippi, New Mexico, and West Virginia. These three states are the three states with the least government revenue per capita, and all three are in the 66th to 88th percentile for Medicaid and Medicare expenditures per capita. Alaska has joined this group of exceptionally unaffordable states due to the fact that Medicaid and Medicare expenditures there are 4th highest in the nation, and government revenue in Alaska is the 6th lowest in the state.

At the other end of the Government HCAITM, we find states with very high taxes per capita: Minnesota, Delaware, and the District of Columbia.

Figure 4 demonstrates how stark the differences between states can be in Government HCAITM.

Figure 4: Government HCAITM by Jurisdiction for 2021

National HCAITM

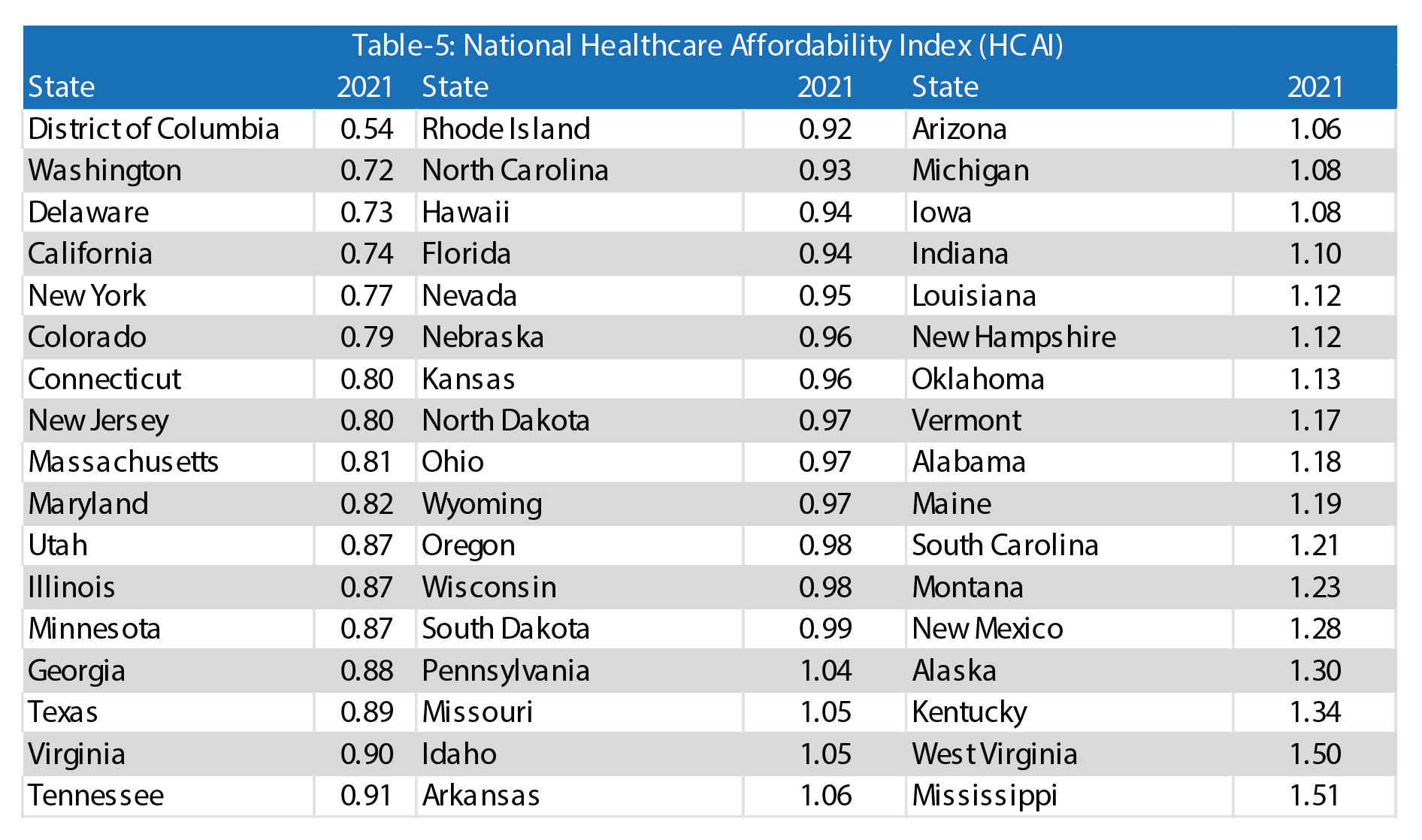

Similar to the Private Payer HCAI, the National HCAI is derived from other indices. It is computed as the straight average of the Employee HCAITM, Employer HCAITM, and Government HCAITM. Results are demonstrated in Table 5 below.

The graphical description of the National HCAITM shown below in Figure 5 looks similar to the graphical depiction of the Government HCAITM. This is because the wide range of values in the Government HCAITM results in some states appearing to have a larger weight placed on the government results. This could be alleviated by using unequal weights in the average; for example, some stakeholders might believe the employee experience should have more clout than the employer or government shares, and so assign a weight of 50% to the employees alone when calculating the National HCAITM. For purposes of our demonstration, though, we have assumed 1/3 of the weight in the average for each of the three constituencies included in our analysis.

Figure 5: 2021 National HCAITM by Jurisdiction

Drivers of Affordability

We have investigated potential drivers of affordability. Given the multitude of variables that affect affordability in a given jurisdiction, we have narrowed our focus to healthcare utilization, business climate, and carrier competition for purposes of this analysis. For purposes of consistency, we have used 2021 data for all relationships analyzed below.

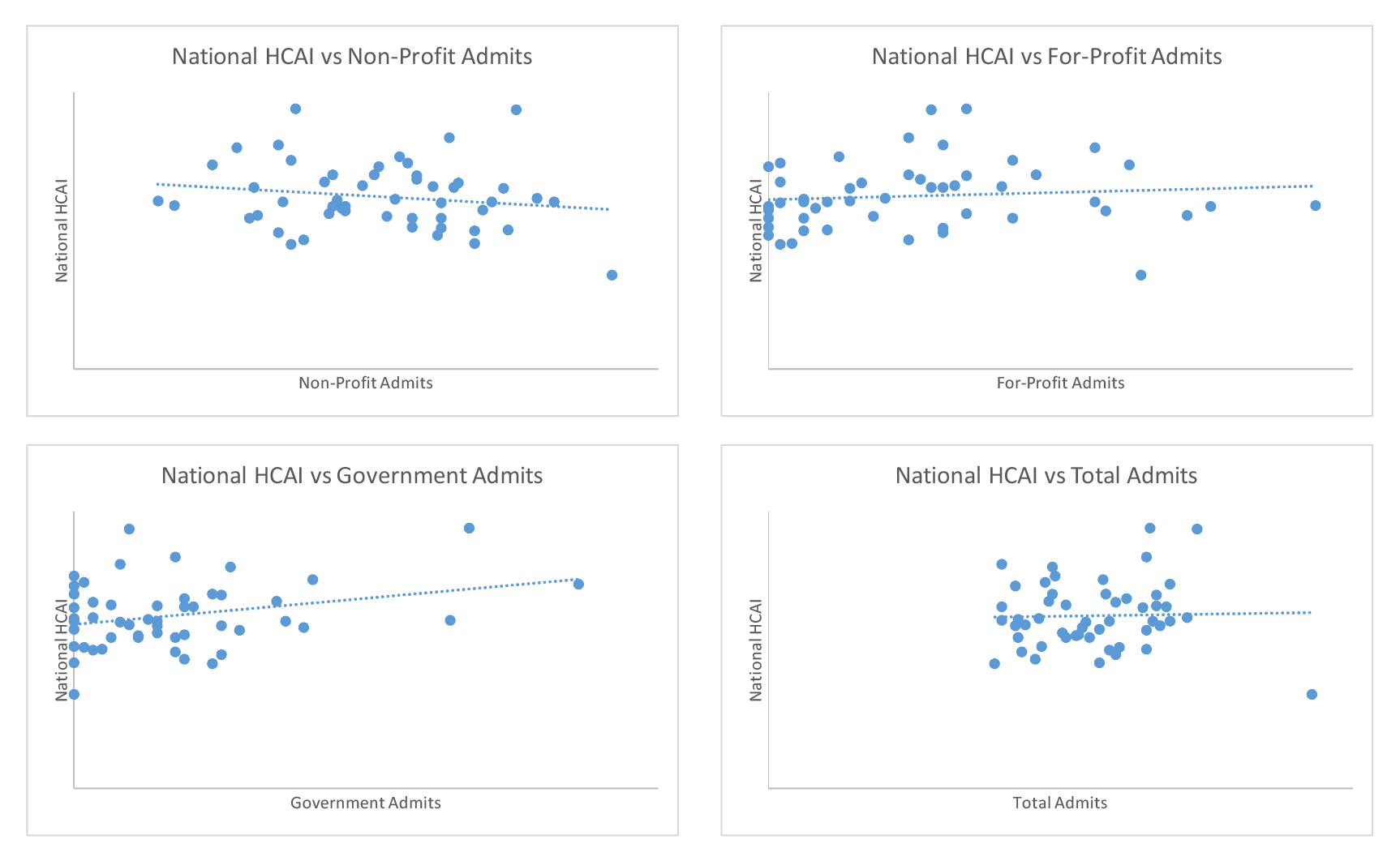

Healthcare Utilization

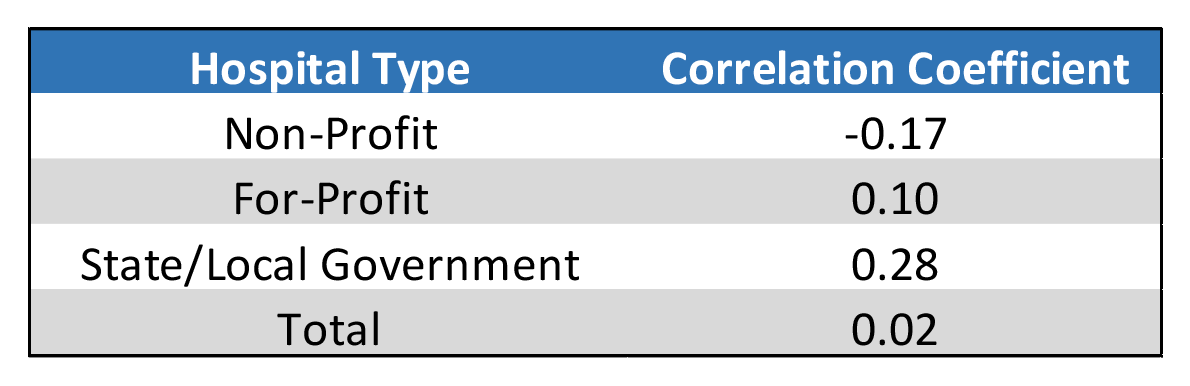

First, we will consider hospital admission rates. Admission rates are available by hospital type: non-profit, for-profit, and government-run. We found that for both for-profit and government-run hospitals, there is a positive correlation between the admissions rate and the affordability index. This is interpreted to mean that for government-run and for-profit hospitals, states that have high inpatient utilization are also relatively less affordable (since the higher the HCAI, the less affordable the region). This is an intuitive result: inpatient stays are much more expensive than ambulatory care, and so more inpatient visits should correspond to higher costs. Conversely, we find that non-profit hospitals have a negative correlation between admissions and HCAI. This could potentially be explained by the greater incentive of for-profit hospitals to encourage admissions in order to increase revenue, whereas non-profit hospitals may have more incentive to redirect patients to the most efficient sites of care.

“Inpatient stays are much more expensive than ambulatory care, and so more inpatient visits should correspond to higher costs.”

Table 6 below demonstrates the correlation coefficients for the relationships described above. As discussed, we find an inverse relationship between National HCAI and non-profit hospital admissions but a direct relationship between National HCAI and both for-profit and state/local government admissions.

Table 6: National HCAITM as a Function of Hospital Admissions Rates

These relationships are further demonstrated in Figure 6 below.

Figure 6: National HCAITM as a Function of Hospital Admission Rates

While admission rates indicate the frequency of hospital utilization, the number of bed days in a hospital can indicate the severity of the problems the hospitals are being used for. The relationship between AHP HCAITM and inpatient bed days is similar to the relationships described above for admissions rates, as shown in Table 7 below.

Table 7: National HCAI as a Function of Hospital Bed Days

Table 7 demonstrates that non-profit hospital bed days are inversely related to HCAI, while for-profit and government-run hospitals’ bed days are directly related to HCAI. This may be explained by the same factors driving the relationship between affordability and admissions rates.

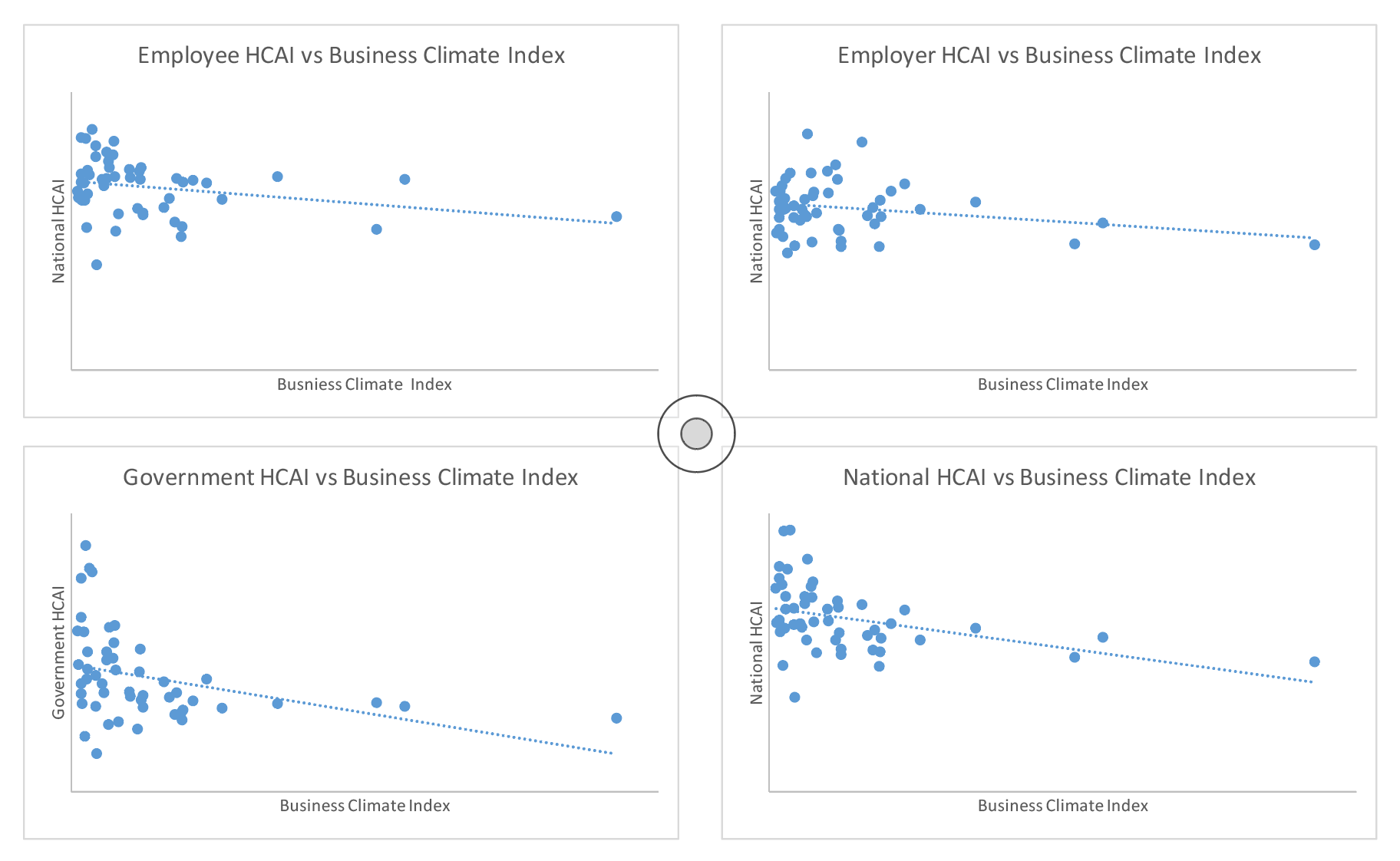

Business Climate

Next, we will investigate the relationship between business climate and affordability. We find that for every variation of HCAITM, jurisdictions with a more robust business climate have relatively greater affordability. This is demonstrated in Table 8 and Figure 7 below through the moderately strong inverse relationships between HCAITM and business climate index.

Table 8 AHP HCAITM as a Function of Business Climate

Figure 7: AHP HCAITM as a Function of Business Climate

We also investigated the relationship between the unemployment rate and HCAITM. The correlation coefficient between Government HCAITM and the unemployment rate is 0.07. This can be explained by considering costs; as the unemployment rate rises, more individuals begin to qualify for public programs such as Medicaid, which raises costs for the government and thus decreases affordability. On the other hand, there is a negative relationship (-0.31) between Employer HCAITM and the unemployment rate. This implies that in a strong labor market, employers’ income rises such that affordability increases. There appears to be no relationship (0.10) between Employee HCAITM and unemployment, which implies that the income gains accruing to employers in a tight labor market aren’t typically fully passed through to the employees.

Competition

We have compared HCAITM to the degree of competitiveness in the large group and small group markets using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). Low values of HHI indicate more competitive markets while high values of HHI indicate less competitive markets. The correlation coefficient between National HCAITM and Large Group HHI is 0.59 while the correlation coefficient between National HCAI and Small Group HHI is 0.26.

This indicates that less competitive markets are less affordable. The direct relationships can be observed in Figure 8, below.

Figure 8: National HCAITM as a Function of Competitiveness

Market competitiveness has the strongest relationship to HCAITM of all the potential drivers that we considered for this analysis. This indicates that stakeholders have cause to be worried about mergers and acquisitions between carriers as they grow ever larger.

Future Outlook

Growth in health expenditures will outpace income growth for all payers for the foreseeable future. For 2022 to 2031, national health expenditures are expected to grow at an average annual rate of 5.4%. Meanwhile, per the Congressional Budget Office, real GDP growth is expected to be at most 4.6% over the next ten years. In the absence of a major change in the healthcare landscape, all payers can expect to experience Healthcare becoming more unaffordable over the next decade.

Conclusion

Though cost is an important factor in healthcare affordability (and likely an easier lever to pull), we firmly believe the ability to pay should also be considered in any proposed solution to the rising cost of healthcare. If current higher than desired inflation levels continue, Healthcare costs will also continue to increase at higher than desired levels most likely decreasing future Healthcare affordability unless the economy experiences a significant rebound.

The projections are not encouraging, but there still is some cause for optimism. Reducing Healthcare costs continues to be a national topic of concern. Medicare’s expansion of value-based care initiatives will likely help improve healthcare affordability. Other solutions being implemented by innovative providers and payers also have great potential for improvement in affordability (e.g., increasing care management effectiveness, using the appropriate situs for end-of-life care, and improving population health).

As we continue to propose and debate new Healthcare solutions, we must consider their effect on cost and ability to pay. In doing so, we may be able to stall or reverse some of the worrying trends in unaffordability.

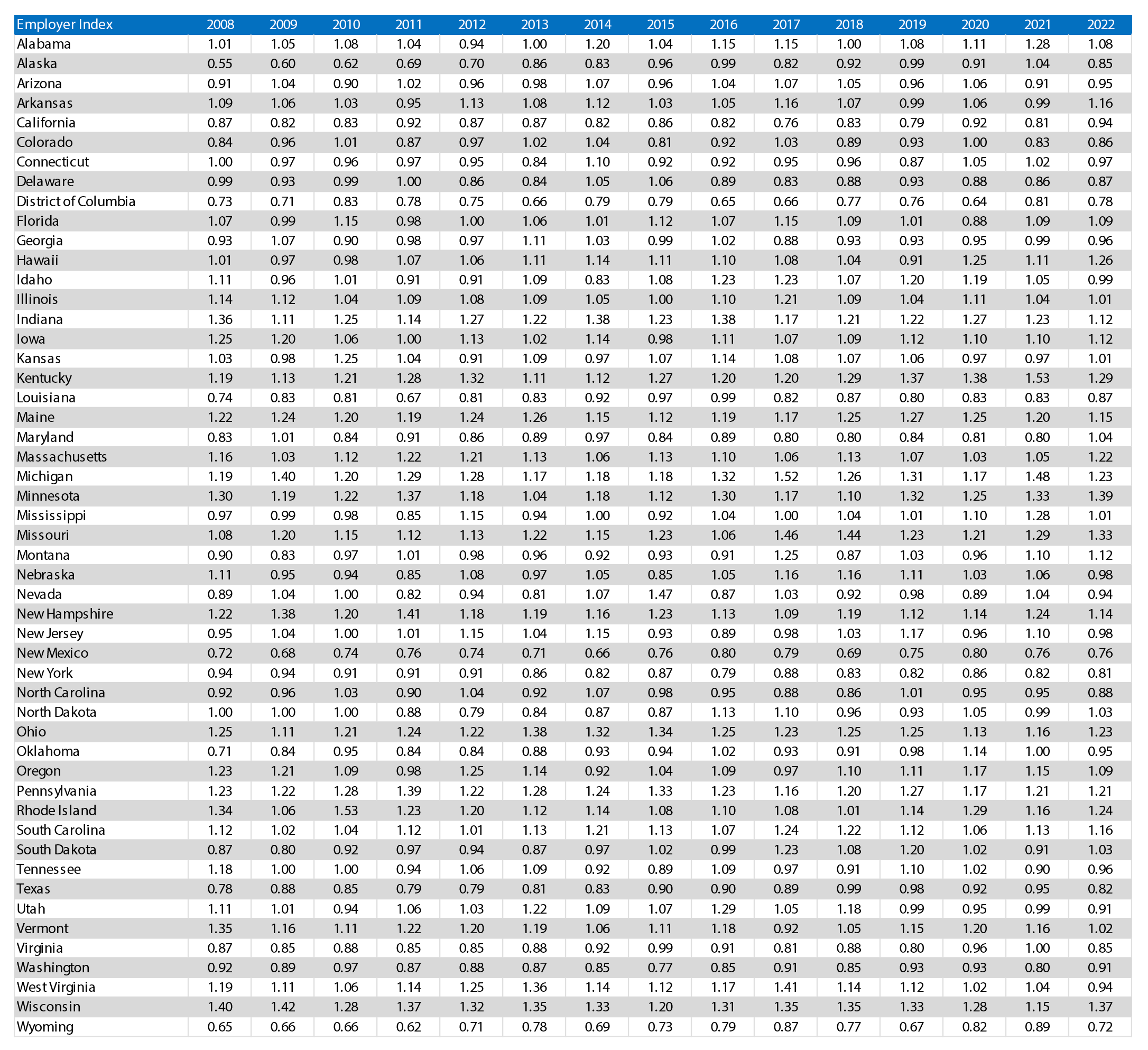

Appendix A: HCAITM History Tables

Employer Index

Employee Index

Private Payer

Government Index

National Index

Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.