Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.

What You Need to Know About Shared Savings Financial Targets

A Brief History of Risk-Based Contracting

Risk based contracting, also known as Value-Based Reimbursement, or VBR, has existed in one form or another for many years, as a method for payers to put some of the responsibility for controlling costs and quality onto the providers. VBR rose to prominence in the US in the 1990’s with HMOs but fell out of favor due to consumer backlash. Recently there has been a resurgence in risk-based contracting. One of the most common types of VBR contracts is shared savings agreements.

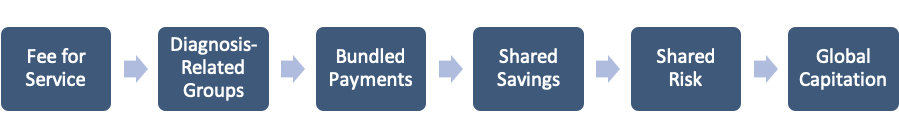

Contracts between payers and providers can be shown on a spectrum depending on how much risk is assumed by the provider, and how much remains with the payer. Value-Based Reimbursement arrangements bridge the gap between Fee for Service, where the providers assume no risk, and Global Capitation, where providers assume all of the risk.

Shared Savings and Shared Risk are two types of arrangements that exist under the umbrella of Value-based reimbursement. Under both of these arrangements, a provider’s actual experience is compared to a contractually agreed upon financial target. Under shared savings arrangements, providers are paid a portion of any savings that are generated when their actual experience is lower than the financial target. Under shared risk arrangements, providers must also pay back a portion of any loss that is generated when their actual experience is higher than the financial target.

VBR is often used by payers to encourage providers to assume more risk over time with contracts that begin as shared savings, or “upside-only” arrangements, and turn in to shared risk, or “two-sided” arrangements after a few years. Providers on shared risk arrangements may also be encouraged to take responsibility for larger percentages of savings and losses over time, progressing further along the spectrum toward global capitation.

The Role of Financial Targets

The financial target serves a critical role in a shared savings agreement, as the benchmark that actual experience is compared to in order to determine savings. While the purpose of the financial target is straight-forward, determining the appropriate target is often much less clear. Determining a target that is both reasonable and achievable is not only a critical step toward a successful VBR arrangement, but also requires a collaborative effort and the expertise of both payers and providers.

If a financial target is too low, the provider organization will quickly discover that it cannot realize a savings and may lose interest in becoming a more efficient and effective operation. Likewise, if a target is set too high, financial incentive payments will be too easy for the provider organization to achieve, resulting in the provider organization having little incentive to maximize its efficiency and effectiveness.

The Two Most Common Types of Financial Targets Used in Shared Savings Arrangements

Financial Targets

The type of financial targets included in Shared Savings Arrangements typically fall into one of two broad categories, a Cost of Care PMPM or Loss Ratio target. Within these broad categories there are a wide variety of ways that these targets can be determined. For example, whether or not an adjustment for measurement period large claimants is included in a loss ratio target, or a rebasing adjustment is made to the target to account for prior period savings is included in a cost of care target.

Cost of Care PMPM Targets

A cost of care PMPM target is typically based on the historical experience of a cohort similar to the population being measured. This historical PMPM is then trended and adjusted to reflect the expected makeup of the measurement period population. The advantage of using a cost of care PMPM target is that it focuses the shared savings calculation on the one item that providers have the most direct control over; the cost of care.

A disadvantage of this type of target is that significant attention needs to be dedicated to determining the appropriate trend and adjustments applied to the historical cost of care when determining the target. These adjustments are typically calculated by the payer’s actuarial staff, and the provider organization may not have the specific expertise to verify that these adjustments are appropriate for the population being measured.

The table below shows the simplified development of a cost of care PMPM financial target:

| Cost of Care Target PMPM Development Step | Metric | Formula Key |

| Base Period Claims PMPM | $400.00 | A |

| Cost of Care Trend | 7.0% | B |

| Cost of Care Target PMPM (Base Period Basis) | $428.00 | C = A x (1 + B) |

| Aggregate Adjustment Factor | 1.0502 | D |

| Cost of Care Target PMPM (Measurement Period Basis) | $449.49 | E = C x D |

Loss Ratio Targets

The loss ratio method of target setting adds a premium component and bases the target off the ratio of the expected incurred claims to the expected premium. One advantage of this type of target is that it incentivizes the provider to maximize diagnosis coding efforts, which in turn optimizes the risk adjustment and total revenue position of the payer. Risk adjustment is an important component of Medicare Advantage and ACA plan revenues.

A disadvantage of the loss ratio method is that including premium in the target may add additional risk to the provider. Member-specific premium rates, especially those developed under community rating rules, can be set to be insufficient when compared to the member’s projected claims. For example, the ACA requires that premiums be set using a 3:1 age rating curve. These age factors, even when combined with risk adjustment transfers, may be insufficient to cover the projected claims and expenses of specific members whose projected claims would more likely fit a 6:1 age curve. The table below shows how this risk is compounded if the actual mix of members is older than what was expected when the premium rates were developed.

| Age Group | Expected Member Months | Actual Member Months | Projected Claims PMPM | Premium PMPM | Loss Ratio |

| 14 | 10,000 | 4,750 | $125.00 | $204.74 | 61.1% |

| 24 | 10,000 | 7,125 | $175.00 | $267.63 | 65.4% |

| 34 | 10,000 | 8,500 | $240.00 | $324.91 | 73.9% |

| 44 | 10,000 | 12,500 | $305.00 | $373.88 | 81.6% |

| 54 | 10,000 | 15,750 | $505.00 | $571.40 | 88.4% |

| 64 | 10,000 | 11,375 | $750.00 | $802.90 | 93.4% |

| Price Weighted Average | $350.00 | $424.24 | 82.5% | ||

| Actual Weighted Average | $402.97 | $474.12 | 85.0% | ||

How Financial Targets are Developed

Both cost of care PMPM and loss ratio targets used in shared savings agreements are typically set by the payer’s actuarial staff and are often subject actuarial judgement. Understanding how the assumptions and adjustments used in setting the final targets are calculated can give providers a better understanding of whether these targets are reasonable and achievable.

Trend Development

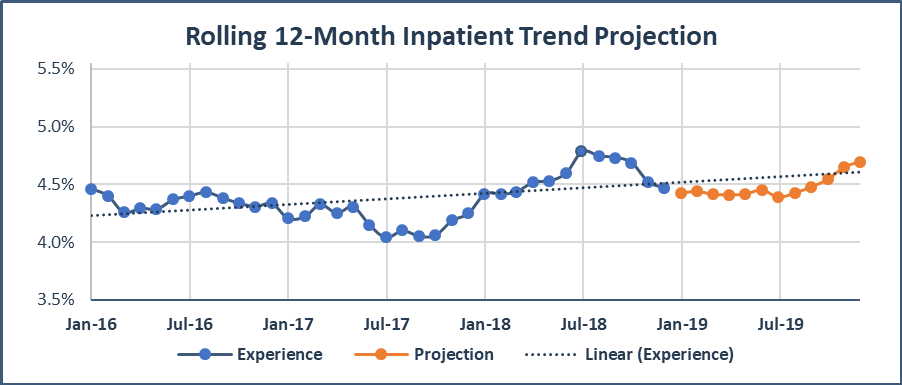

The cost of care trend is the key assumption used by the payer’s actuaries to calculate the cost of care PMPM target. The trends used may be the pricing trends used in premium development, or trends that are calculated just for setting the financial target. In either case, trends are typically developed by collecting and normalizing historical utilization, unit cost, and PMPM experience data grouped by category of service. The actuaries then project these normalized historical patterns into the future using a variety of statistical methods and actuarial judgement in order to develop the expected normalized trends. Finally, the actuaries adjust the expected normalized trend for known projection period changes, such as work days and increases or decreases in provider reimbursement. The exhibit below shows an example of an Inpatient PMPM trend projection using a simple linear regression adjusted for work days and assuming flat provider reimbursement rates.

The data used, adjustments made, and final trend “picks”, are each subject to judgement by the actuaries when setting the trends and each can have a significant impact on the final cost of care PMPM target.

Another method of setting cost of care PMPM target uses a trend based on a retrospective industry average, or independent third-party trend. This method assumes that the third-party trend represents what the provider organization’s trends would have been without the shared savings arrangement. A benefit of using third-party trends is the objectivity in trend setting, although there can be questions about the appropriateness of industry averages for a specific provider organization.

Premium Rate Development

The premium component of a loss ratio target is developed by the payer’s actuaries in two steps. In the first step, the projected claims cost portion of the premium is developed by trending historical experience forward and adjusting for expected changes between the experience and effective periods. The final premium rate starts with the projected claims, then adds projected non-benefit expenses for administrative expenses, broker’s commissions, taxes, fees, risk load, etc. Similar to the trend development used in a cost of care target, both the projected claims cost and non-benefit expenses can be subject to actuarial judgement that could result in a loss ratio target that is either higher or lower than might be appropriate. The premium component of loss ratio targets may also be subject to management discretion on how competitively the premium will be priced.

Adjustments to Targets

Targets set using either the cost of care PMPM or loss ratio methods are often considered starting points by payers, who then make additional adjustments to set the final targets. Some examples of these adjustments are:

- Prior Year Savings or Losses Adjustment

Under some multi-year shared savings agreements the financial targets for the entire contract are set in advance. More commonly, the targets are “rebased” each year, and the financial target in a given year is set based on the provider organization’s performance in the previous year. Because of this rebasing, providers are subject to a “ratcheting effect” in which past success under the program leads to lower targets over time and can eventually lead to unrealistic targets for the provider. To combat the ratchet effect, these types of shared savings agreements often include an adjustment for a portion of prior period savings or losses achieved by the provider. - Adjustment for Insurance Risk

To encourage provider groups to take more financial risk over time, many shared savings agreements start as upside-only, and transition to two sided agreements where the provider is responsible for a larger percentage of any shared savings or losses. As the provider sharing percentages increases, these contracts often include a small discount to the financial target. This discount serves as backstop for the payer, to ensure that they are able to cover their expenses before they begin sharing savings with the providers. Alternatively, some contracts may include a small increase to the target for the benefit of the providers, as the providers assume a portion of the insurance risk and should receive a portion of the profit margins built in to the insurance premium. - Relative Provider Efficiency

When financial targets are based in part on broad historical data rather than provider specific data (for example a payer’s statewide average trends), financial targets are often adjusted for the efficiency of specific provider organizations. The less efficient provider organizations will have their targets decreased to reflect the fact that it is easier to “trim the fat” compared to more efficient providers.

Reconciling Financial Results to Shared Savings Financial Targets

Adjustments Needed for an Equitable Comparison

A shared savings agreement is ideally intended to measure savings created by the providers and not reward random fluctuations or simple good luck. In order do this, there are a number of adjustments and other considerations that are often used to try to isolate the impact of true savings.

- Large Claimants

By their nature, the number of large claims in any given year is unpredictable, and the costs of the large claims that do occur often cannot be managed in any significant way.Normalizing for the impact of large claims should be considered when setting the target and measuring results. For agreements that base a given year’s target on the prior year’s results, an abnormally high frequency and/or severity of large claims in one year could lead to a higher target, and thus higher savings, than appropriate in the following year. Similarly, a provider organization could see any potential shared savings eliminated by a small increase in the number or size of catastrophic claims. - Mix Changes

There are a number of ways that changes in the membership that make up the base period and measurement period populations can impact financial results that are out of the provider organizations’ control. It is important to attempt to eliminate these population “mix” issues that would otherwise distort the impact of care management initiatives or other interventions that would lower the cost of care and improve quality. The table below shows an example of an adjustment for a variety of types of mix changes:

-

Adjustment Base Period Measurement Period Formula Key Demographic 1.1000 1.1250 A Risk Score 1.3500 1.4000 B Network 0.9970 0.9950 C Benefit Plan 0.9800 0.9700 D Geographic 1.0350 1.0375 E Aggregate Factor 1.5017 1.5771 F = A x B x C x D x E Aggregate Factor Adjustment 1.0502 G – FMP ÷ FBP H

Target PMPM (Base Period Basis) $500.00 Target PMPM (Measurement Period Basis) $525.10 I = G x H

- Cohort Selection

Shared savings agreements typically do not use the exact same population in both the experience period and measurement periods. This is done to avoid a “Reversion to the Mean”. Reversion to the Mean refers to the fact that high cost members in one period are typically not high cost in the future due to either death, or recovery from an acute condition. However, to ensure equivalence, the same rules must be used to create the experience and measurement populations from the broader population. For example, the cohort in both periods should be selected using the same member attribution methodology, or the same member diagnoses exclusion methodology, number of months the member is enrolled, etc.

Data Requirements

The data that payers must share with provider organizations in order for the provider organization to properly assess the shared savings calculations can vary significantly from organization to organization, and from contract to contract.

Provider organizations should require payers to provide not only enough data to reconcile the financial results, but also enough data to independently validate any adjustments made to either the target or financial results. What data will be provided, as well as the format and timing of any data provided should be negotiated and agreed upon prior to beginning the agreement.

Additionally, it is important for payers to provide periodic and timely membership and performance reports to provider organizations so that provider organizations can validate the members that they are responsible for and to give provider organizations the best opportunity to manage the care of their membership.

Quality Targets, and Care Management Fees

Two components of many shared savings arrangements that can make or break a provider’s success are Care Management Fees and Quality Targets.

Quality Targets

Providers must generate savings under a shared savings agreement without sacrificing quality in patient care. Quality targets ensure that providers do not benefit from shared savings at the expense of quality. A quality target can function as a minimum cut-off below which providers receive no shared savings, as a percentage modifier that reduces shared saving based on performance, or as a combination of the two. For two-sided arrangements, these percentage modifiers function so that shared savings are maximized when quality is high and minimized when quality is low, and that shared losses are maximized when quality is low and minimized when quality is high. The table below shows how various quality adjusted shared savings and losses are calculated using a percentage quality modifier, a maximum sharing rate of 60%, and a minimum quality score of 30%.

| A | B | C | D | |

| Gross Savings or Losses | Sharing Rate | Quality Score | Quality Adjusted Savings or Losses | Formula Key |

| $100 | 60% | 100% | $60 | If C > = 30% Then D = A x B x C Else D = 0 |

| $100 | 60% | 80% | $48 | |

| $100 | 60% | 60% | $36 | |

| $100 | 60% | 40% | $24 | |

| $100 | 60% | 20% | $0 | |

| $100 | 60% | 0% | $0 | |

| ($100) | 60% | 100% | ($40) | If (1 – B x C) < 60% Then D = A x (1 – B x C) Else D = A x 60% |

| ($100) | 60% | 80% | ($52) | |

| ($100) | 60% | 60% | ($60) | |

| ($100) | 60% | 40% | ($60) | |

| ($100) | 60% | 20% | ($60) | |

| ($100) | 60% | 0% | ($60) |

The measures included in determining the quality score can vary significantly from one contract to another but are usually based on some standard metrics such as HEDIS or Stars measures, and providers should consider whether the measures are appropriate for their population.

Care Management Fees

The purpose of Care Management Fees is two-fold. First, care management fees are intended to cover any start-up expenses that a provider might incur in order to change the way they operate to deliver more efficient, value-based care. These types of expenses could include hiring additional staff to perform care management or the purchase of new technology or infrastructure such as telemedicine systems that allow patients to video-chat with care managers. The second purpose is to cover any ongoing care coordination or care management services that providers will deliver but cannot bill for under VBR. These types of expenses include care planning, patient education, and coordinating care between multiple providers.

Care management fees are often used as a temporary incentive for the provider organization to encourage participation in shared savings agreements. The fees are typically paid only for the first few years of a given agreement, after which it is assumed that providers have successfully established managed care practices. It is assumed that these practices will generate shared savings payments, and thus the care management fees will no longer be needed to “bridge the gap”.

In some cases, these care management fees may be subject to the minimum quality thresholds discussed above, however in many cases, only shared savings are impacted. These fees can also either be guaranteed or be contingent on a provider organization generating savings, depending on the specific agreement. For example, if an agreement includes a $5 per member per month care management fee that is contingent on savings, a provider organization may be required to generate at least $5 of savings in order to receive the full care management fee.

How to Determine if the Financial Target is Fair and Attainable

Success under a Value Based Reimbursement arrangement is often as dependent on the due diligence undertaken by the provider organization before a shared savings agreement is signed as it is on the provider organization’s efforts to lower the costs and improve the quality of the care they provide. There are a number of ways a provider organization can determine whether they will be successful before entering into any risk-based agreement.

Understanding and Validating Program Assumptions

In most cases, a provider organization will not be able to know the specific financial target they will be measured against before entering into a shared-savings arrangement. The organization should, however, be able to understand and determine the fairness of the methodology that will be used to develop the specific parameters of the final shared savings calculation.

Furthermore, as provider organizations move from upside-only shared savings to two-sided shared risk arrangements, they will be responsible for a portion of the insurance risk that was previously entirely the responsibility of the payer. As a result, provider organizations should not only understand, but should also have a measure of control over the final rate development of any underlying insurance product.

Readiness Assessments

Part of determining whether or not a financial target is attainable is determining if your organization is prepared to succeed under value-based reimbursement. While insurers typically have much more complete information on how shared savings targets will be set, the provider organizations will have a much better idea as to whether or not their organization can be successful as a risk-bearing entity. A provider readiness assessment is an objective evaluation that aims to answer several questions regarding a provider organization’s ability to successfully assume risk, such as:

- How efficiently does the provider organization manage the care of its patients currently? Each organization will eventually reach a point where they are “ideally managed” and there are few inefficiencies left to cut. As a provider organization approaches this point, success under VBR may become more difficult.

- Does the provider organization have sufficient influence on individual providers? A provider organization cannot succeed under VBR unless the actual providers are motivated to change the way they deliver care to focus on quality and efficiency.

- Is the provider organization prepared to manage care well enough to generate savings? For example, provider organization will need to have sufficient monitoring and reporting capabilities to identify care management opportunities.

- Does the provider organization have the correct internal payment model to be successful under VBR? A successful payment model will appropriately incentivize primary care providers since they can have a large impact on efficient management of care.

- Can the provider achieve sufficient margins under the proposed rates? Many shared savings agreements include reduced fee schedules as part of the agreements, and provider organizations need to consider whether or not they can cover their expenses under the new rates with, or without earning shared savings.

Statistical Models

Provider organizations considering a move to value-based reimbursement are often presented with a set of deterministic scenarios showing potential financial outcomes based on a set of assumptions. Deterministic scenarios, such as those shown in the table below, do little to inform the providers organization of how likely any of these possible scenarios are to occur.

| Scenario | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Formula Key |

| Projected Membership | 16,500 | 16,500 | 16,500 | 16,500 | 16,500 | 16,500 | 16,500 | A |

| Financial Target | $425 | $425 | $425 | $425 | $425 | $425 | $425 | B |

| Cost of Care PMPM | $457 | $446 | $436 | $425 | $414 | $404 | $393 | C |

| Gross Savings or Losses PMPM | ($31.88) | ($21.25) | ($10.62) | $0.00 | $10.63 | $21.25 | $31.88 | D = B – C |

| Sharing Rate | 50% | 50% | 50% | 50% | 50% | 50% | 50% | E |

| Shared Savings or Losses PMPM | ($15.94) | ($10.63) | ($5.31) | $0.00 | $5.31 | $10.63 | $15.94 | F = D x E |

| Total Shared Savings or Losses | ($3.2M) | ($2.1M) | ($1.1M) | $.0M | $1.1M | $2.1M | $3.2M | G = 12 x A x F |

Provider organizations can get a better idea of the shared savings that can be expected under a specific with the use of a statistical model. A useful model of any shared savings arrangement can be developed using historical claims and enrollment data, information on the provider organization’s cost structure, and the specific aspects of the proposed agreement. Using this information and statistical techniques such as Monte Carlo simulation or bootstrapping, a provider organization can develop a report showing the likelihood of various outcomes under the shared savings arrangement. Provider organizations can then decide if the contract is expected to meet their internal financial goals while consider the organization’s risk tolerance. A provider organization can also use the results of these models to prioritize potential contract edits during negotiations with payers.

Expanding upon the previous example, the table below shows that by including the modeled probability of each of the seven scenarios, this provider organization is expected to generate any shared savings only 11% of the time and to have shared losses of $1.6 million on average.

| Scenario | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Formula Key |

| Total Shared Savings or Losses | ($3.2M) | ($2.1M) | ($1.1M) | $.0M | $1.1M | $2.1M | $3.2M | A |

| Probability of Outcome | 25.0% | 40.0% | 16.0% | 8.0% | 6.0% | 3.0% | 2.0% | B |

| Weighted Savings or Losses | ($0.8M) | ($0.8M) | ($0.2M) | $0.0M | $0.1M | $0.1M | $0.1M | C = A x B |

| Expected Savings or Losses | ($1.6M) | D = Sum of C | ||||||

Conclusion

The success of a value-based reimbursement arrangement, including shared savings arrangements, ultimately relies on the existence of an open and cooperative partnership between the provider organization and the payer. This type of partnership requires the meaningful sharing of data, assumptions, and expectations between both parties. To be part of a successful value-based reimbursement arrangement, a provider organization will need to be able to make informed decisions about the proposed arrangement including the appropriateness of the financial target, the likelihood of the organization’s financial success, and the financial impact of specific contract provisions.

About the Author

Joe Slater, FSA, MAAA, is a Partner and Consulting Actuary with Axene Health Partners, LLC and is based in AHP’s Charlotte, NC office.

About the Author

John J. Culkin, ASA, MAAA is a Consulting Actuary at Axene Health Partners, LLC and is based in AHP’s Charlotte, NC office.