Economics students are baptized in the basics of supply and demand the moment they step into their first classroom. The free market involves buyers and sellers who participate in a bilateral tug-of-war over price and product quality. These dueling forces eventually settle at an equilibrium that appropriately balances the collective interest of each side[1].

Healthcare operates in a different economics universe. For the sake of simplicity, let’s focus primarily on a scenario involving the individual health insurance market. Replace the two sides of buyers and sellers with a threesome of P’s (Patients, Providers, and Payers) playing a trio of simultaneous tug-of-war games amongst themselves. In this economic universe, the patients, providers, and payers each play individual tug-of-war with the other two P’s. Payers attempt a “buy low, sell high” arbitrage strategy by battling for a low price with providers in order to sell those same services to patients for a relatively fixed price with respect to utilization. The payers earn their profit by assuming downside risk that would typically prohibit patients from sufficiently utilizing provider services to maintain good health. The negotiation between patient and provider typically center around quality of service. Unlike traditional economics, the patient utilizes and negotiates quality of service with the provider largely irrespective of price (aside from copays, which are a relatively minimal percentage of the total cost of care). This is the world of healthcare. Stakes run high, emotions run higher, and the government meticulously referees the tug-of-wars.

A Moral Hazard

The multiple stakeholders and many layers of administration between the patient’s instance of payment and provider’s instance of service leads to unfettered increases in utilization and cost of care in a fee-for-service model. Once the patient and provider have negotiated their prices with the payer, moral hazard dictates that each will maximize their own interests. The patient will visit the doctor (especially ER doctors when convenient) as many times as desired to feel healthy, and the doctor gladly provides any number of services because it earns revenue (and suppliers of medical equipment and pharmaceuticals will also be grateful). As moral hazard runs rampant and more companies enter the industry to stake out a niche in administration, medical technology, drugs, etc., the payer must continually increase prices until the system becomes too expensive and patients can’t afford their premiums.

The problems created by fee-for-service and moral hazard become exacerbated when an aggressively profit-maximizing private equity firm becomes involved.

Meanwhile, private equity firms (who are accustomed to making large investment returns in the more traditional economics universe) have entered healthcare with indomitable force. Healthcare provides them the opportunity to make similarly appealing returns by acquiring providers (or their suppliers) with minimal downside risk because patients invariably utilize their services. The problems created by fee-for-service and moral hazard become exacerbated when an aggressively profit-maximizing private equity firm becomes involved. Private equity is simply behaving as it very successfully does in other industries. However, healthcare provides a unique economic universe which removes normal free market forces that might provide a “checks and balances” to profit maximization by providers. Furthermore, sloppiness caused by cost-cutting measures to maximize profit can lead to irreparable mistakes in an emotionally charged business[2].

Private Equity’s Increasing Presence

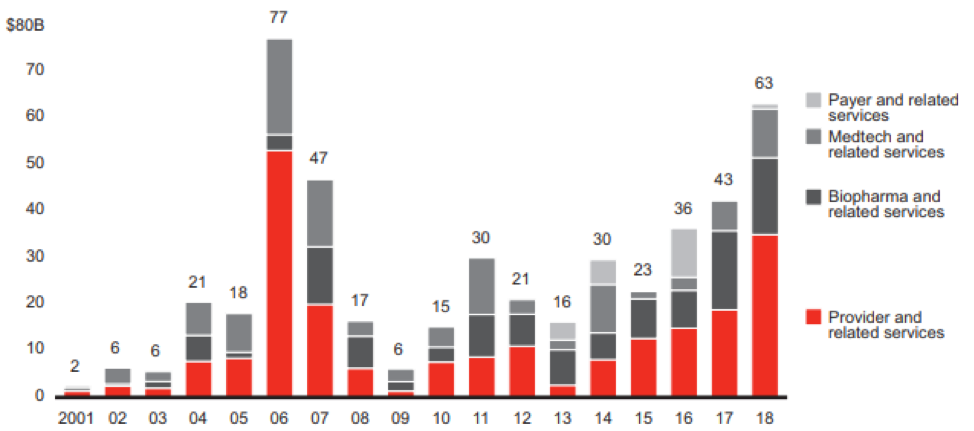

The increasing presence of private equity in healthcare is demonstrated in Figure 1. Since 2001 the global healthcare buyout deal value has increased at a compounded annual growth rate of 22.5%. Over the last 5 years, the growth rate has been 31.5% and largely driven by provider and related services with fee-for-service payment structures. This trend is not anticipated to slow down in 2019[3]. Private equity has realized the opportunity created by the moral hazard of healthcare economics and made the most investment in providers and their suppliers. Relatively little investment has been made in payers because they play a reactionary role to the moral hazard and profit has become regulated with the introduction of federally mandated loss ratios.

Figure 1 – Global Healthcare Buyout Deal Value[4]

An Antidote for Moral Hazard

However, the relationship between payers and providers is beginning to evolve. A shift towards value-based payment methods has occurred in recent years in an attempt to align the three stakeholders of healthcare and motivate providers to be more price-conscious in their interactions with patients[5]. Under these payment structures, the provider bears the incentive to provide quality care at a lower cost than a traditional fee-for-service structure. For many private equity firms, value-based reimbursement is unfamiliar territory because provider groups assume risk like payers, which contrasts with most other private equity investments. While the utilization incentives for patients remain unchanged, providers must adhere to best-practices and keep costs commiserate with patient risk scores in order to remain profitable. Private equity firms should be wary of ignoring these new payment models because they promote a “healthier” healthcare system and are gaining momentum. A robust due diligence effort should ensure that value exists in deals under value-based reimbursement.

Holistic Value

Whether private equity firms are engaged in deals with fee-for-service or value-based payment structures, it serves their long-term interests to consider the value a business adds to all three healthcare stakeholders. A service or product which only benefits providers and patients but has negative consequences on payers will likely not attain long-term adoption and success. Healthcare requires and thrives when synergies are maximized among patients, providers and payers. Despite short-term profits, there can be drastic consequences if one of the three P’s is suffering because it will require intervention by the very important and powerful tug-of-war referee: government. Providers, patients, and payers all have their own means by which to call upon the government when the game starts to become lopsided. Providers and payers have lobbyists, which receive their fair share of blame and contempt from the media. Patients have the power of the vote. The 2020 election has already become inundated with talk of healthcare reform which would increase referee involvement to abate moral hazard and lower costs. Whether the comprehensive legislation being proposed is good, bad, or ugly is beyond the scope of this article. However, the most valuable private equity deals are those that bring value to all three P’s of healthcare. This will ensure that profits will remain unjeopardized by government intervention.

In order to assess a private equity deal’s holistic value, an effective process should outline the various measurements used to assess value for each stakeholder, map existing and any proposed care pathways, and actuarially determine the weighted value of all measurements to arrive at a value index for each perspective[6]. AHP has applied this process to many areas including new drugs, procedures, biomedical instruments, surgical techniques, project assessment, virtual medicine, and more.

Conclusion

Private equity plays a very important role in the broader economy by discovering and optimizing value. However, the market forces which comprise healthcare are very different from those of most industries. The numerous stakeholders and close attention paid by the government necessitate a more careful and holistic consideration of value. This article began by focusing primarily on the individual health insurance market. While additional stakeholders must be considered in commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid, which increases complexity, the consequences of moral hazard and lessons regarding the role of private equity remain the same.

Endnotes

[1]I recognize that a “tug-of-war” is not a perfect analogy for the market forces described in this article. Two sides are not always in direct opposition to each other and can attain “win-win” outcomes. Nevertheless, I will use the analogy for the sake of simplistic illustration.

[4]“Global Healthcare Private Equity and Corporate M&A Report 2019”, Bain & Company, https://www.bain.com/globalassets/editorial-disruptors/2019/healthcare-pe-report/bain_report_global_healthcare_private_equity_and_corporate_m_and_a_report_2019.pdf

[5]AHP has written extensively about value-based reimbursement. For definition and description see https://axenehp.com/implementing-value-based-reimbursement-pathway-success/and https://axenehp.com/closing-loop-value-based-reimbursement-incentive-programs/

[6]https://axenehp.com/question-not-answer-need-assessment-value/

About the Author

Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.