Health insurers are required to hold minimum levels of surplus each year. However, the exact amount a health insurer chooses to hold can vary significantly from one insurer to the next. Why is that? Are there any guiding principles established surrounding what amount of surplus is considered best practice for the health insurance industry?

In personal finance, we must consider how much money to set aside as a “rainy-day” fund to help weather potential future financial storms. To establish this fund, we develop some sort of logic behind the exact amount to hold, such as six months of expenses or 30% of our annual income. This specific logic depends on our personal risk tolerance as well as the volatility of our income and expenses. In a similar vein, health insurers also evaluate the proper amount of surplus to set aside to ensure their business continues to run smoothly in the face of various potential obstacles. But how do they go about doing this?

While the specific answers depend on the context of each health insurer, there are some guiding boundary markers that are fairly universal.

RBC Minimums

A good starting benchmark when considering surplus levels is the minimum risk-based capital (“RBC”) requirements developed by the NAIC.

“By plugging in a few key financial metrics from the health insurers’ annual statements, the RBC calculation provides a resulting RBC benchmark specific to that insurer.”

Within the US insurance marketplace, all health insurers are required to report their RBC levels annually. This reporting metric helps the state regulators to understand how likely it is that a health insurer will become insolvent in the near future. The RBC metric was developed by considering the key risks to surplus that all health insurers are likely to face. By plugging in a few key financial metrics from the health insurers’ annual statements, the RBC calculation provides a resulting RBC benchmark specific to that insurer. The health insurer then compares its total surplus (or “Total Adjusted Capital”) against the RBC benchmark to see how many multiples of the benchmark they currently hold.

For example, consider health insurer XYZ with the following financial statistics:

Risk-Based Capital After Covariance (“RBCAC”): $100M

Authorized Control Level (“ACL”) = 50% of RBCAC = 50% * $100M = $50M

Total Adjusted Capital (“TAC”): $175M

Based on these metrics, the RBC ratio is calculated as:

RBC Ratio = TAC / ACL = $175M / $50M = 350%

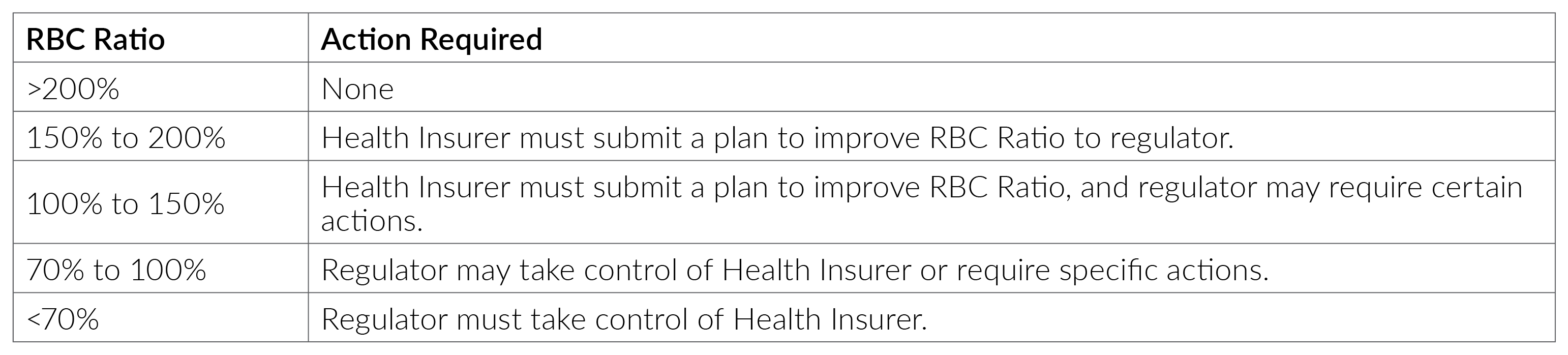

There are specific regulatory consequences for falling below various levels of RBC.

Health insurers are strongly incentivized to steer clear of these low levels of RBC as health insurers would prefer to maintain their independence in strategy and decision-making.

“A good rule of thumb is that approximately a 200% RBC ratio represents a 95% probability the surplus will not fall below zero in the next five years.”

In addition to avoiding regulatory interference, health insurers can use the RBC benchmark to understand their potential risk exposure. An important piece of information provided by the RBC ratio is the implied surplus-at-risk benchmark. A good rule of thumb is that approximately a 200% RBC ratio represents a 95% probability the surplus will not fall below zero in the next five years. As health insurers consider their risk appetite and risk tolerance level, the RBC ratio can provide a valuable proxy for discussion.

The 200% RBC ratio estimate is notably accurate for health RBC due to the dominance of underwriting risk in the formula. The underwriting risk formula was designed to specifically estimate the amount of surplus required such that claims volatility over a five-year time horizon the surplus would fall below zero in no more than 5% of model simulations.[1] Since underwriting risk is well over 90% of the 200% RBC ratio level, the 200% RBC ratio can be used as a meaningful proxy for this confidence level and time frame for health insurers.

Reasons to Hold Capital Beyond RBC Minimums

In addition to avoiding the consequences of RBC minimums, there are many other legitimate reasons to hold significantly higher levels of capital.

First, the health insurer may have additional risks not accounted for in the RBC formula such as risks of not getting future rate increases approved, or other external factors. These additional risk factors could materially change the potential volatility of future surplus projections.

Additionally, the health plan may view the RBC minimums as insufficient due to the organization holding a lower risk appetite than set in the RBC formula. For example, if the RBC formula assumes holding 200% of RBC will results in insolvency in the next five years 5 out of 100 times but the insurer prefers to hold capital such that insolvency in the next five years happens 2 out of 100 times, then their preference will lead to higher RBC.

Finally, there could be reasons that now is not the best time to deploy the excess capital currently held by the insurer. Time-sensitive opportunities worth waiting for could include strategic acquisitions, specific marketing campaigns, adding human capital, and unforeseen innovation and development opportunities. Without excess capital, the insurer would be limited in their ability to take advantage of opportunities as they come along over time.

Reasons to Set Limits on Holding Excess Capital

While more capital than the RBC minimums may be needed, there is also a likely upper bound to the capital a health insurer should hold.

First, there is evidence to suggest insurance regulators may negatively view high levels of RBC. This is because regulators are interested in maintaining a stable and competitive marketplace that provides consumers with affordable health insurance options. If health insurers are accumulating high levels of surplus, then that would imply the market is not very competitive and that consumers are overpaying. Similarly, it seems to imply that health insurers are setting their premiums too high and therefore the regulators may balk at an insurer’s request for future premium rate increases in this scenario.

Second, if the health insurer is publicly held, the high levels of the surplus could be viewed negatively by shareholders. Shareholders are investing in health insurance, not health insurance plus the health insurer’s asset portfolio. To the extent the excess capital cannot be justified by one of the reasons listed in the prior section, shareholders would prefer to receive that capital back in the form of a buyback so they can decide how that additional capital is invested.

Endnotes

[1] Page 3 of the AAA response from Steve Drutz to the NAIC (E) Working Group on January 21, 2022, titled “Re: Request for Comprehensive Review of the H2—Underwriting Risk Component and Managed Care Credit Calculation in the Health Risk-Based Capital Formula” and located at https://content.naic.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Att5_American_Academy_of_Actuaries_H2_Review_Underwriting_Risk_Report_01.21.2022.pdf

Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.