Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.

It’s widely predicted that 2023 will pose broad economic challenges. Reasons abound for a potential recession, but in many ways, it’s time to pay the piper for actions taken during COVID. That’s not to suggest no fiscal and economic measures should’ve been taken in 2020, but it’s foolish to expect there would be zero consequences. Healthcare is not exempt from the turbulence ahead and the prominence of value-based care (VBC) creates some unique challenges. A number of concurrent events in 2020 could lead to even greater distress in healthcare than many anticipate. These events and possible consequences are outlined below.

1. Healthcare utilization was suppressed due to COVID.

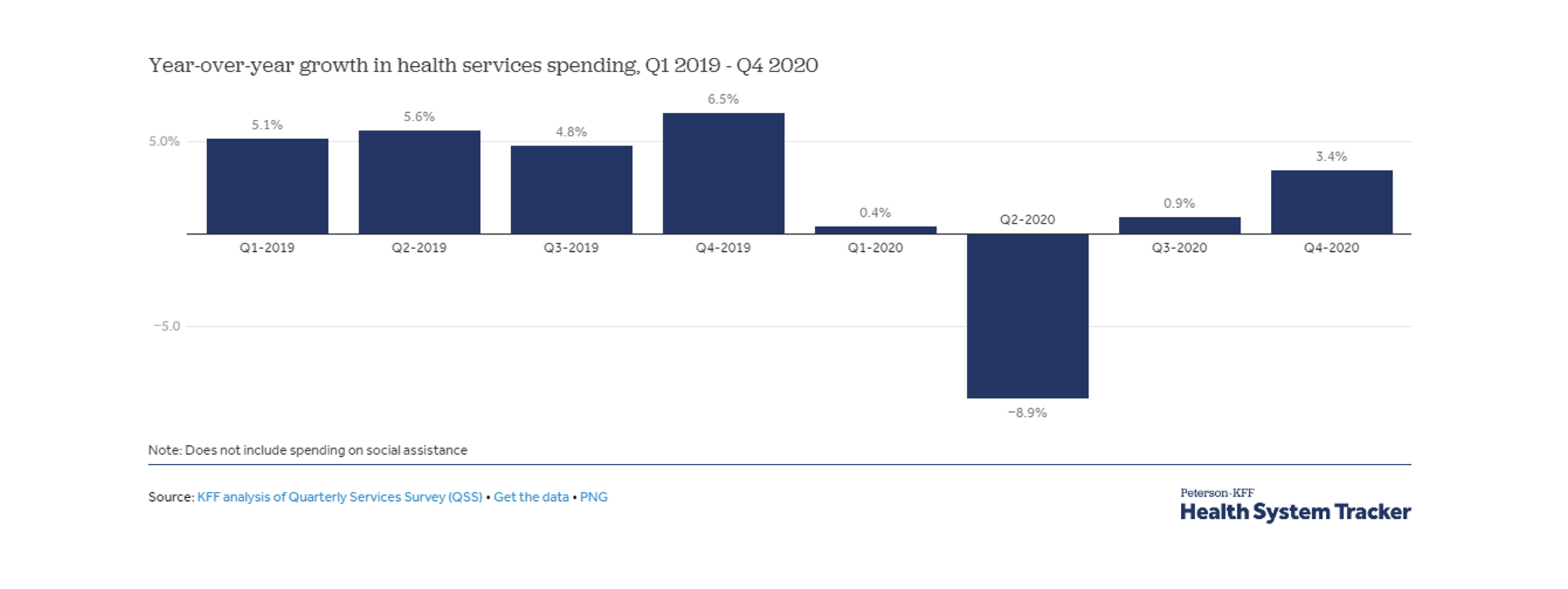

Like many other industries, healthcare experienced partial shutdowns that suppressed utilization across many specialties. Elective care took the largest hit and, although telemedicine became widely accepted, health services revenue fell by 1% in 2020 compared to 2020.

2. Providers in VBC arrangements profited while others under fee-for-service (FFS) struggled.

The pain of utilization suppression was felt most sharply by providers in FFS reimbursement agreements. Like health insurers who assume risk in return for a relatively reliable revenue stream, providers in value-based care arrangements benefited from steady revenue despite services decreasing. In fact, profitability soared for some providers.

3. Historic cash infusion by the federal reserve and government created billions of dry powder seeking

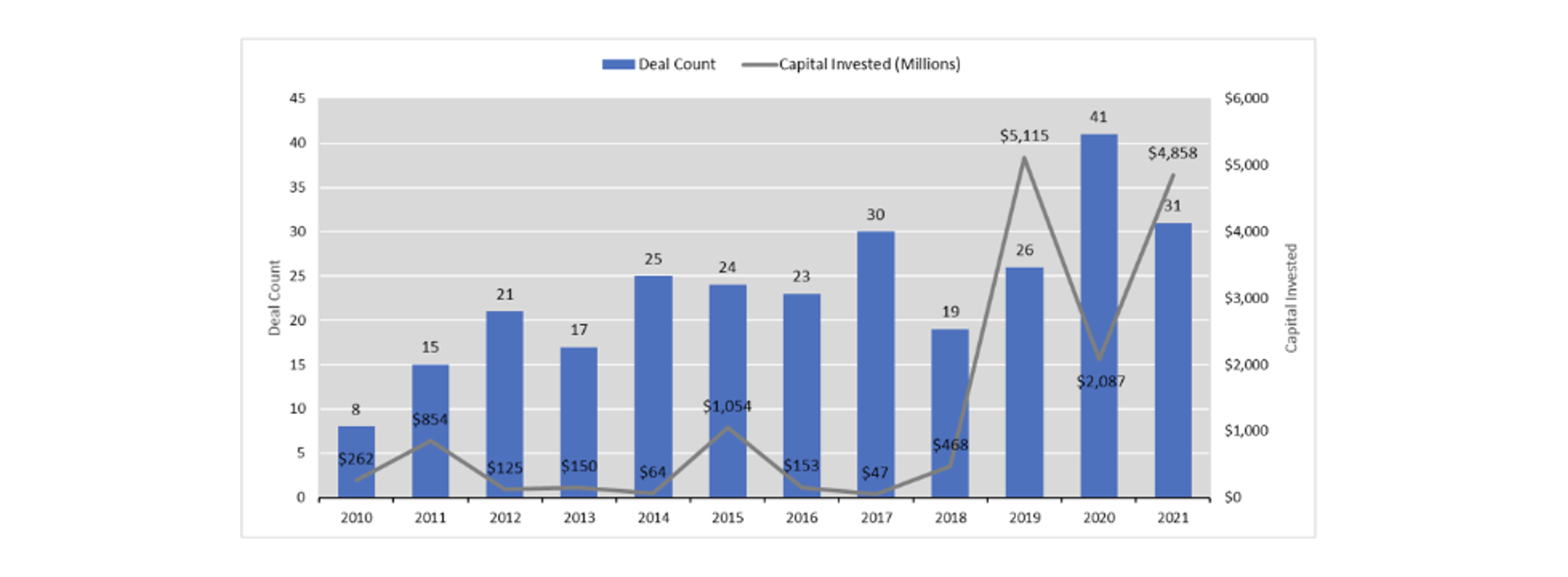

The M2 money supply grew 27% in 2020-2021, creating more than $1.5 trillion of money available to fund managers worldwide. This created a supply and demand problem for private equity as historic amounts of money began seeking limited investment opportunities. Valuations for provider groups soared as investors competed to create more attractive bids.

4. Both (1) and (2) made VBC appear to be an attractive investment thesis in and of itself, rather than emphasizing the providers who manage care well.

Provider profitability under VBC in 2020 created the appearance of attractive investment opportunities. However, this was the product of a once-in-a-lifetime economic event rather than a signal of the inherent success of such reimbursement contracts. Furthermore, little expertise was required to appear successful under VBC during 2020 which allowed some providers to create an illusion of a valuable investment opportunity.

5. Investors (some without prior healthcare experience) spent the next two years investing significant money into VBC platforms.

Due to supply-demand problems created by (3) and the appearance of VBC as a burgeoning investment opportunity, significant money began being invested into providers engaged in VBC. Deal activity for primary care groups and other provider platforms with alternative reimbursement arrangements accelerated aggressively. Not only did the number of healthcare-focused PE firms increase, but many other PE firms without deep healthcare expertise began making investments into VBC as well. The attractiveness of VBC overshadowed the fact that it is extremely complex to navigate and requires greater technical skill than FFS to operate profitably.

6. As inflation permeates healthcare, legacy VBC contracts face a heightened risk of shrinking profit margins.

Inflation has shaken every industry, but healthcare inflation tends to lag general inflation because it takes time for multi-year reimbursement contracts to expire and be renegotiated. In the meantime, rising wages and overhead costs apply margin pressure as VBC revenue fails to adjust proportionately. Providers lack the tools they had to fight inflation under FFS and must exert more technical skills in care management. Profit margins must be sustained to justify the historical valuations investors paid for VBC platforms in 2020-2021. Fortunately, there is still time remaining in the investment cycle to “right the ship” and achieve a positive ROI upon exit.

Fortunately, there is still time remaining in the investment cycle to “right the ship” and achieve a positive ROI upon exit.

7.Profitability can be salvaged by providers understanding their own claims data and properly identifying care management opportunities.

A lot of investment money is depending on the ability of provider groups to successfully navigate a challenging period under VBC. Rather than simply increasing services performed, providers must rely on technical care management skills to maintain profitability.

This is best demonstrated with an actuarial cost model such as the AHP MARS tool, which breaks out unit cost and utilization across a variety of services and specialties.

Although (7) is difficult, the good news for investors is it’s achievable. It starts with understanding the claims data of attributed members and comparing it to ideal care management benchmarks. This is best demonstrated with an actuarial cost model such as the AHP MARS tool, which breaks out unit cost and utilization across a variety of services and specialties. A simultaneous clinical review by care management experts will typically validate any actuarial findings and illuminate the most actionable items. Investors would’ve benefited from incorporating these steps into their original due diligence. Although this requires a financial commitment, the stakes have rarely been higher for so much capital in healthcare.

About the Author