Abstract

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is recognized for its role in reducing the uninsured rate in the United States. The federal financial commitment has expanded Medicaid eligibility and provided incentives for people to enroll in individual markets for the first time. Underneath the surface, the structural individual market design results in convoluted mathematical dynamics[1] that challenge stakeholders to understand and improve markets. There has been historical reluctance to freely admit these challenges, partially to avoid potentially providing leverage to ACA detractors. To improve ACA markets, we must first be honest about some of its illogical consequences. For many of us, this is a hard pill to swallow.

Introduction

The pivotal moment[2] in the 1999 science fiction action film The Matrix involves the central character having to choose between irrevocable binary options. He can elect to swallow a blue pill and continue to live in comfortable obliviousness to the harsh truth of the world around him. Alternatively, he can swallow a red pill and clearly see the cruel and unpleasant truth. He selects the red pill and experiences the punishing, real world. In the remaining scenes, we learn that boldly accepting the truth was more difficult in the short-term but worthwhile in the end.

As the tenth anniversary[3] of the ACA nears, we must come to understand that we have collectively swallowed a blue pill. This is historically justifiable. Many of us appreciate the ACA’s accomplishments and we don’t want to dwell on its faults. Implementation of the ACA was the turning point in the reduction of the nation’s uninsured rate; Medicaid has been expanded to fill gaps among the low-income population, unpopular underwriting practices have been prohibited, and generous premium subsidies have reduced net premiums for some individual consumers. As we celebrate and seek to preserve these gains, the common perception[4] is that the law continues to face political and legal threats. Admission of ACA weaknesses can be recognized as potentially adding ammunition to these threats, and a candid discussion of ACA structural concerns is something ACA advocates have plausibly avoided. Even stakeholders who acknowledge deficiencies today and seek to “build on the ACA” are not interested in dissecting its faults, but simply adding more government funding which only further conceals the inherent structural issues[5] from public understanding.

The ACA’s challenges have been evident: lower than expected enrollment, high premiums, lack of attractiveness to some demographic segments. This article is not a discussion of these challenges or overall ACA performance; it’s a discussion about the ACA’s inherent individual market design. The intent is to communicate the ACA’s flawed design, discuss resulting market responses, and communicate necessary solutions. To accomplish that, we need to be candid about these flaws, something we have not only been reticent to do, but something we don’t really understand because the underlying unique dynamics are so convoluted and counterintuitive to all we know about health care markets and costs.

The “blue pill” assessment is not a criticism of the ACA, but acknowledgment that we have willfully avoided being forthcoming and honest with ourselves about its mathematically unintended outcomes. Fortunately, our collective decision is not irrevocable. We can swallow the red pill today and appreciate the uncomfortable actualities that are foundational to ACA mechanics. Improvements to the ACA framework can only be achieved directly with such willingness.

The nonintuitive nature of ACA mechanics, which are often not fully grasped even by actuaries and state regulators, has led to policy decisions rife with unintended consequences, including beneficial changes that many stakeholders initially proclaimed were harmful.[6] The ACA dynamics can be understood, but not with a traditional health insurance approach. It requires accepting mathematical dynamics that are plainly true but clearly irrational. For example, lower premiums often increase consumer costs and create problems that most observers do not anticipate.

Unfortunately, most of the justification or criticism of the ACA has been grounded in political[7] theory rather than analytical substance: “It involves too much government control”, “it was a compromise with the insurance industry“, or “it was a Heritage Foundation idea 30 years ago”. Such assertions are irrelevant and unhelpful. Occasionally, some commentators recognize that understanding the ACA transcends common sense, political reporting, and talking points and offer this ‘: “Don’t trust your gut on this one, the media, or President Trump. Trust math.”[8] The ACA dynamics are all about math and not politics. Once we agree on that, we are one step closer to facing the challenges together. Let’s explore ACA dynamics and their ramifications.

Low Cost and Competition Create Problems for Lower-Income Enrollees

At the midpoint of the most recent open enrollment period (11/1/19-12/15/19), a Health Affairs blog opened with this counterintuitive claim: “In 2020, Affordable Care Act (ACA) health insurance Marketplace premiums will increase for significant segments of the currently enrolled population. This is because gross premiums are decreasing in the ACA Marketplaces for the second year in a row. (emphasis mine)”[9] The first section of this blog is aptly titled The Strange Math Of The Marketplaces: Why Premium Decreases Can Increase Costs For Subsidized Enrollees.

To illustrate this counterintuitive dynamic and other similar paradoxes, numerical examples are helpful to facilitate understanding of the mathematical relationships. Examples throughout this article will build on prior tables and concepts.

Lower Gross Premiums Leads to Higher Net Premiums

Affordable coverage in ACA markets is determined based on a sliding scale percentage of income. An enrollee can purchase the second lowest-cost silver tier plan (the “benchmark” plan) with an enrollee contribution equal to the calculated “affordable” percentage of his/her income. The remaining premium (benchmark plan premium rate minus enrollee contribution) is the premium subsidy. Enrollees can carry the dollar amount of this subsidy to other plans, either within the same value tier or not, and purchase less expensive or more expensive coverage.

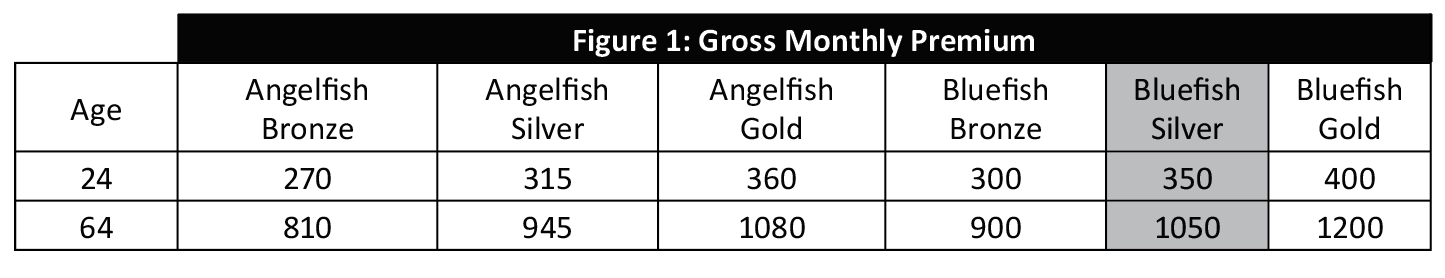

An example of the subsidy calculation methodology is demonstrated below for two individual adults. Figure 1 illustrates the gross monthly premiums for two sample companies, Angelfish and Bluefish, offering Bronze, Silver, and Gold plans.

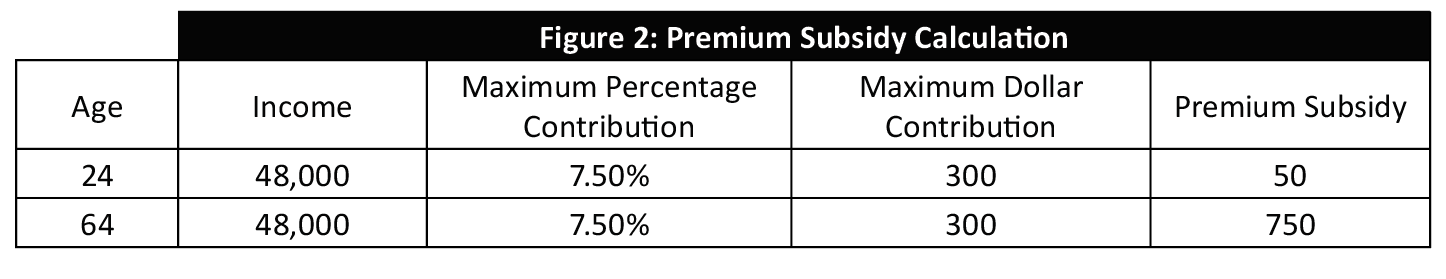

Figure 2 illustrates the subsidy calculation for a particular income level and age. This is determined by calculating the maximum monthly contribution that an enrollee pays for the benchmark plan (Bluefish Silver in this case; for transparency, benchmark plans are shaded in examples). Assuming the maximum contribution percentage of 7.50 percent for an individual with an income of $48,000 (a reasonable approximation but not representative of any year), the maximum monthly contribution for that individual is $300 [$48,000 * 7.50% / 12]. The calculated premium subsidy is the gross monthly premium of the benchmark plan minus the $300 maximum dollar contribution from the enrollee.

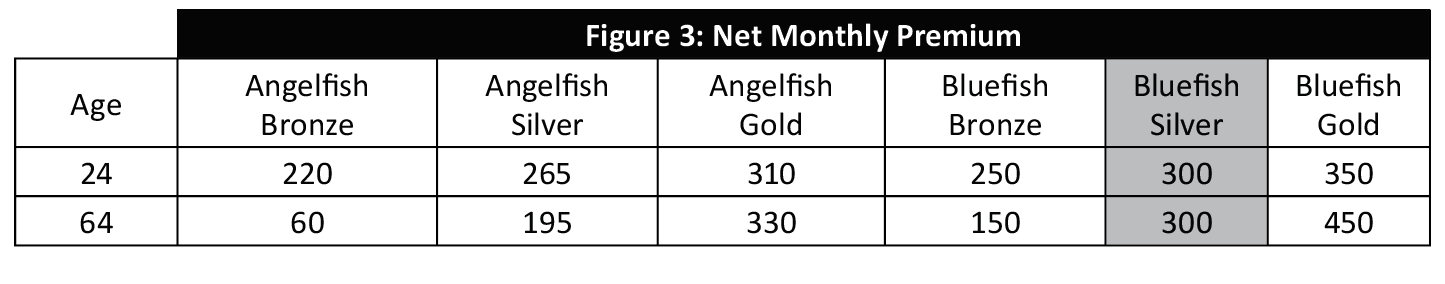

Figure 3 illustrates the net monthly premiums that enrollees pay for each plan in the market after subtracting the premium subsidy from the gross monthly premiums.

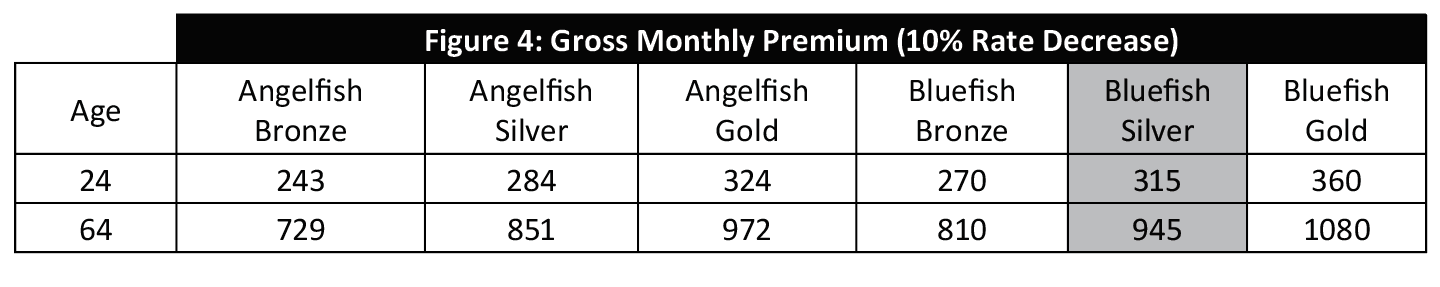

Figure 4 illustrates the gross monthly premiums after a 10% rate decrease. The values in Figure 4 are 10% lower than the values in Figure 1.

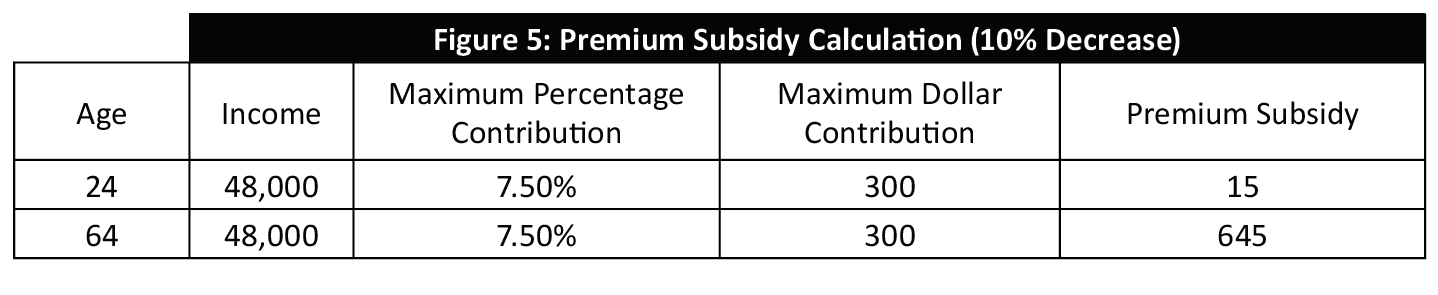

Figure 5 illustrates the subsidy calculation. The premium subsidy is lower because the benchmark plan (Bluefish Silver) premium is lower. The maximum contribution of $300 does not change.

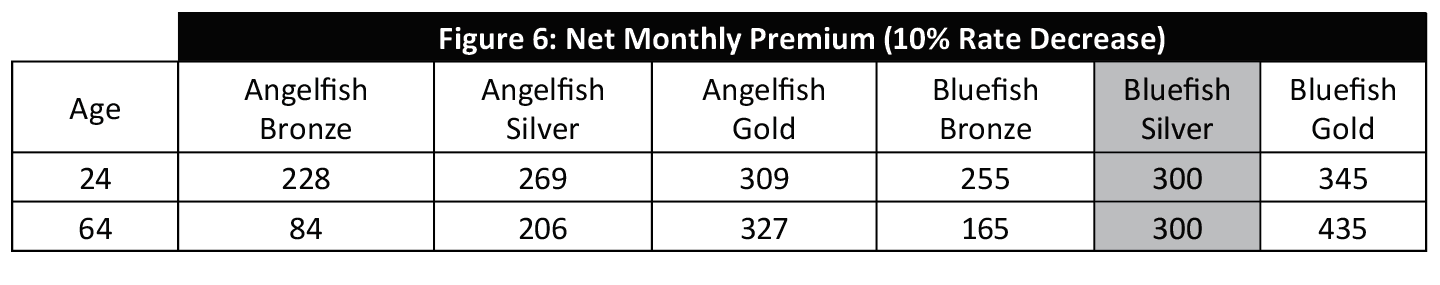

Figure 6 illustrates the resulting net monthly premiums, reflecting both the lower gross premium and the lower premium subsidy.

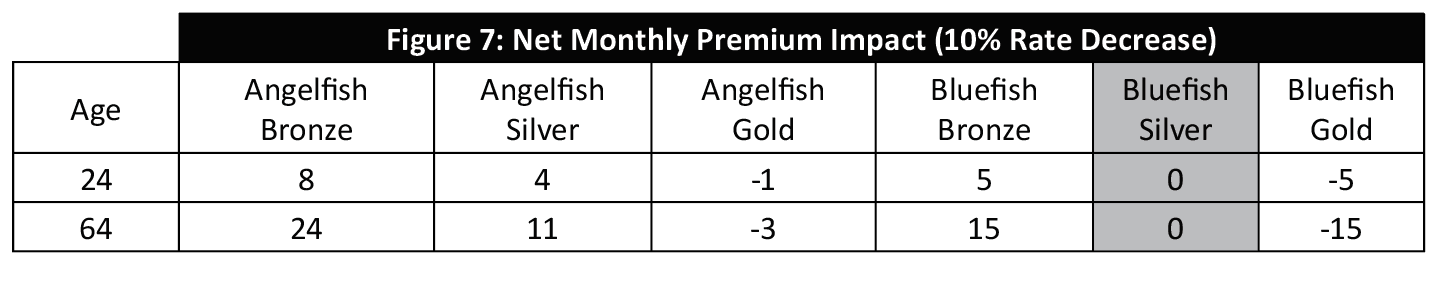

Figure 7 illustrates the resulting net premium impact of the 10% rate decrease, including net increases for plans with prices lower than the benchmark plan.

This counterintuitive and troubling dynamic of lower premiums requiring lower-income enrollees to pay more has been present in ACA mechanics since inception. As premiums didn’t appreciably decrease until 2019[10], it hasn’t been much of a historical public concern.

This is a significant concern, however, for stakeholders interested in implementing innovative solutions that achieve lower costs. As Jon Walker warns, “The more states try to make the exchanges work well and keep insurance premiums low, the more their low-income residents end up needing to pay for insurance.”[11] This convoluted dynamic is not limited to innovative solutions[12]; states that implement reinsurance waivers or reduce premiums during the rate review process are benefitting their higher-income citizens but increasing the premium costs to lower-income individuals.[13] This is a troubling dilemma when properly understood.

The same mathematical formula that benefits consumers when premiums are high also benefits older adults, paradoxically resulting in lower premiums than younger adults of similar income. Note the premium relationships between ages for bronze and silver plans in Figure 3 and Figure 6. As the market primarily attracts subsidized enrollees who gravitate to lower-cost plans, this results in ACA market enrollment older than ACA architects intended.

Competition Increases Prices for Subsidized Consumers

With the rating rules in ACA markets, adequate premium subsidies are required for individual market survival. As premiums are inflated to reflect higher expected costs, premium subsidies provide the necessary purchase incentives for a sustainable market. Unlike other government programs, there is not a linkage between subsidy funding and historical costs. When ACA markets took effect, there was no historical government data to utilize for purposes of determining appropriate funding. Without an established benchmark in place, ACA architects decided to let annual market rates determine the subsidy allocation without regard to the implications.

As a calibration was selected on the benchmark plan (2nd lowest silver) rather than an average or median, an increase in insurer participation alone creates a bias toward compressed premium subsidies. Simply having more data points depresses the second lowest result. As more insurers enter markets (this happened in 2019 and 2020 as favorable conditions[14] developed), the benchmark is naturally based on a lower-cost plan. If benchmarks decline and gross premiums stay the same, consumers pay more.[15] More competition results in a less attractive market and lower enrollment.

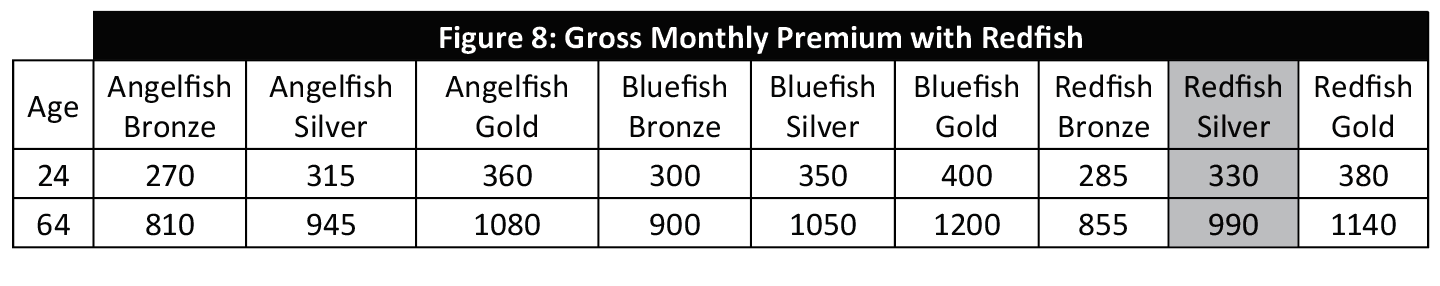

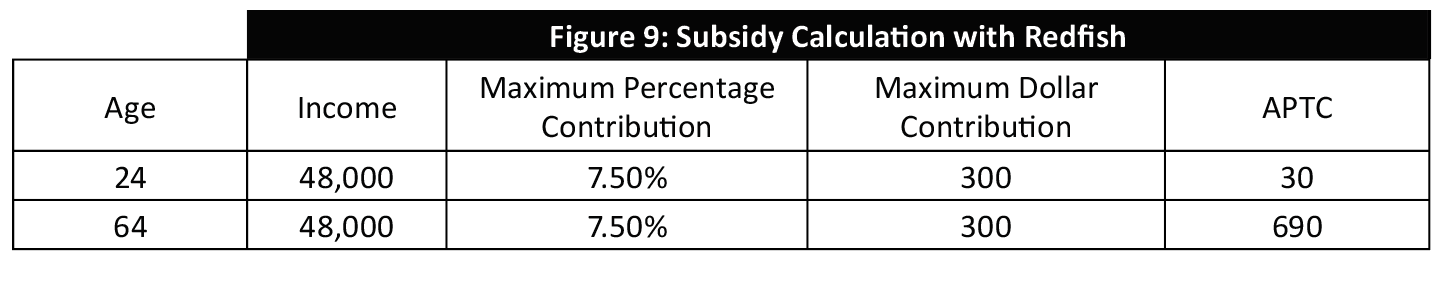

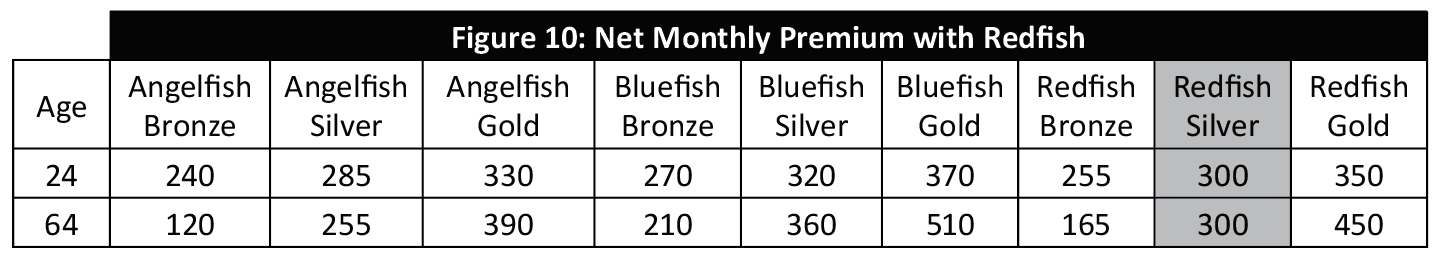

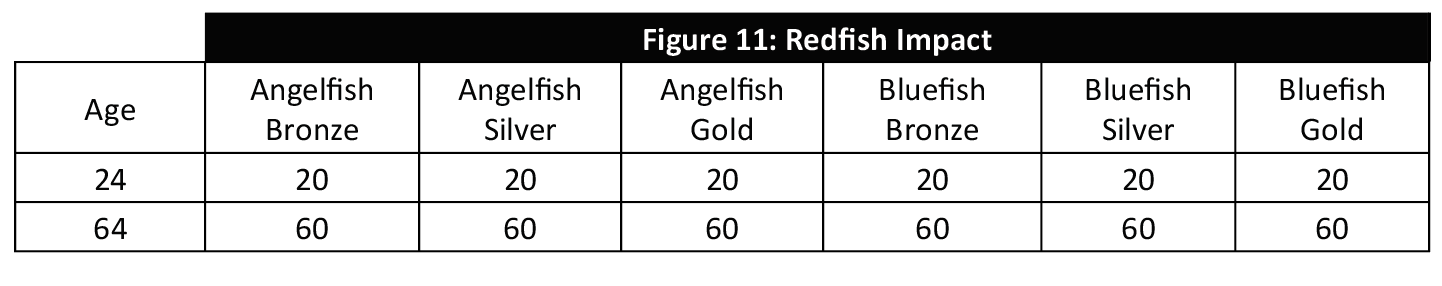

Figures 8-10 illustrate the impact of a new insurer entering the marketplace. Figure 8 is similar to Figure 1, with the addition of the Redfish health plan who has premiums between Angelfish and Bluefish.

Figure 9 is identical to Figure 2 except for the subsidy calculation. The new benchmark plan is Redfish Silver; as the premiums are lower than Bluefish Silver, the subsidies are accordingly lower.

Figure 10 illustrates the net monthly premiums with Redfish in the marketplace. As the subsidies are lower, net premiums are higher than they were in Figure 3 for Angelfish and Bluefish.

Figure 11 illustrates the net premium impact of Redfish’s market entry. The math is straightforward. As the premium subsidies reduce by $20 and $60, net premiums increase by $20 and $60. While Figure 7 illustrates the lower premiums result in subsidized enrollees paying more, Figure 11 demonstrates that more competition increases their net premiums.

Invasive Competition Makes Things Worse

Of course, ACA market risk is not limited to simply the number of competitors. New entrants with unusually low-cost structures[16] can reduce premium subsidies to levels that require enrollees to switch health plans and networks, potentially challenging the viability of traditional insurers to remain in ACA markets. As ‘too little competition’ has been the primary concern[17] in the ACA’s early years, it’s been rare for states to take an interest in avoiding low-cost plans. Some savvy state exchanges have recognized this dynamic and deliberately and perhaps controversially avoided allowing low-cost plans on their platform. In 2017, a health plan in Rhode Island was prevented from joining the exchange due to such anxieties. “The exchange was concerned that the additional low-cost plans would have reduced the subsidies available to all exchange enrollees, making coverage less affordable if people chose plans other than the new low-cost options.”[18]

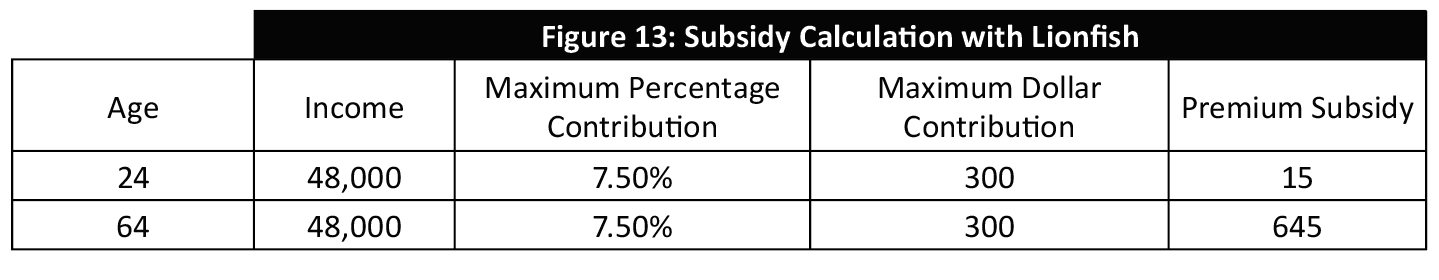

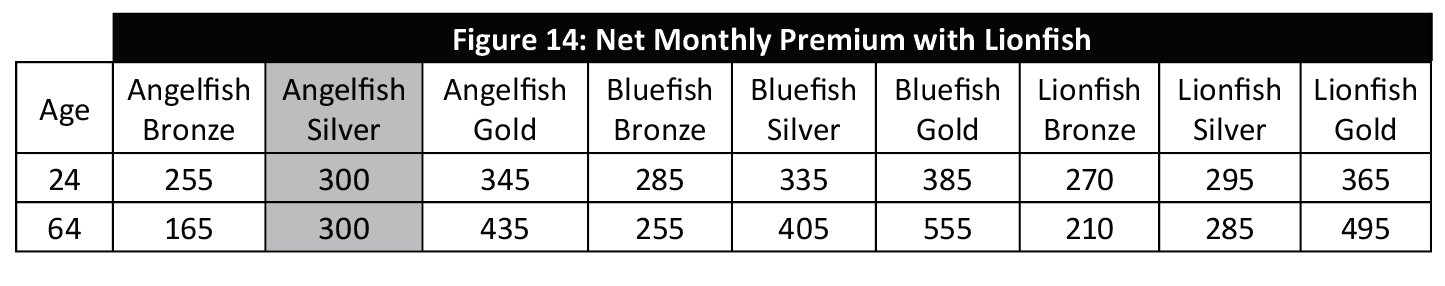

Similar to Figures 8-10, Figures 12-14 illustrate the impact of a new carrier entering the marketplace. Instead of Redfish, the new carrier Lionfish seeks to attract Silver enrollees and has aggressively priced Silver premiums. Figure 12 is similar to Figure 8, with the addition of the Lionfish health plan rather than Redfish.

Figure 13 illustrates a significant premium subsidy reduction relative to Figure 2 due to Lionfish’s market entry. The new benchmark plan is Angelfish Silver; as the premiums are lower than Bluefish Silver, the subsidies are accordingly lower.

Figure 14 illustrates the net monthly premiums with Lionfish in the marketplace.

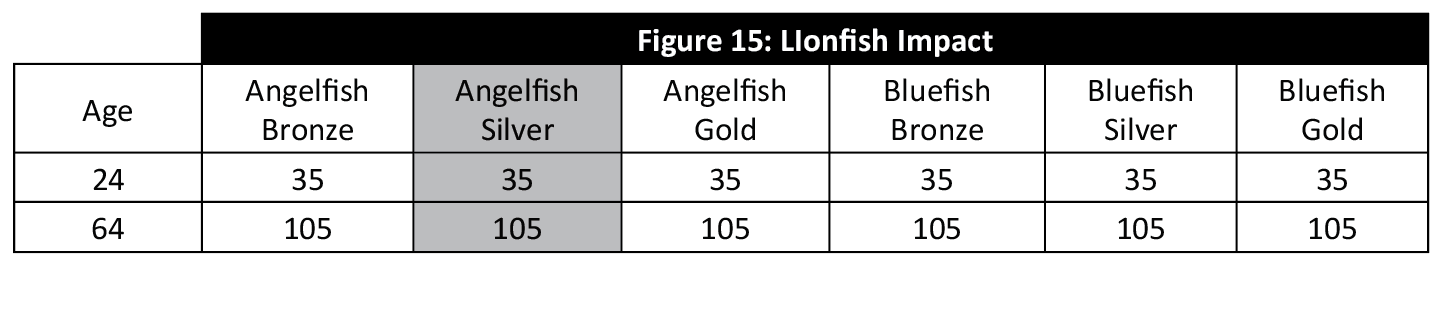

Figure 15 illustrates the Lionfish impact. Hypercompetitive Silver premiums reduce net premiums and subsidies. As Angelfish Silver is now the benchmark plan rather than a plan priced below the benchmarks, its premiums increase as well.

ACA Insurers Don’t Want Healthy People

Insurance companies want to provide coverage for healthy people who have few medical claims and avoid those with high costs and chronic conditions; at least that’s the conventional wisdom. In reality, their survival depends on charging appropriate prices for the risks they assume and they are otherwise fairly indifferent to who they insure.

As the ACA does not allow the rating to vary based on health status, a “risk adjustment” methodology transfers funds from insurers who enroll low-risk individuals to insurers who enroll high-risk individuals.[19] Accordingly, insurers must base their estimates on overall market enrollment, not who they expect to enroll.

Many stakeholders believe the ACA risk-adjustment methodology results in imbalanced assessments[20] that penalize the low cost, well-managed insurers that attract healthy enrollees that the ACA needs to survive. This is not conjecture from outside observers; health plan actuaries have confirmed “healthy doesn’t pay under risk adjustment”[21], the “transfer formula penalizes plans with lower premiums”[22], and “low-cost insurers working to keep the marketplace affordable for individuals are being hit with the formula imbalance”.[23] The former Chief Actuary at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services opined “the current HHS-HCC risk-adjustment model established by CMS is known to understate risk scores for relatively healthy individuals and to overstate them for those with significant health conditions.”[24]

The obvious problem with risk adjustment is that the supply side (in addition to the demand side discussed in previous section) market attractiveness is skewed away from what we collectively agree the risk pool needs to maintain viability.Ultimately, we are left with the challenge that young and healthy individuals have less incentive to enroll, health plans may not want to enroll them, but we all recognize that we need young adults to enroll in the market to preserve the risk pool.

It is worth noting that there are divergent opinions within the industry here regarding the degree of the risk adjustment problem. As the methodology is budget neutral and inequities in the methodology necessarily create winners and losers, there are naturally different insurer viewpoints regarding the equity concerns of the current model.

Risk Adjustment Dilution Will Attract Insurers Who Enroll Low-Risk Consumers

The goal of risk adjustment is to equitably transfer funds from insurers with higher morbidity to insurers with lower morbidity, accounting for the inability to use morbidity as a rating factor. If risk adjustment methodology overcompensates for health status and penalizes insurers who attract low-risk enrollees, a dampening of risk adjustment methodology may provide better equity. The determination of equity is subjective and difficult to measure in the dynamic, multi-variate ACA environment.

A simplistic but common measure of risk adjustment success is the concept of ‘loss ratio compression’.[25] As insurers generally target the similar loss ratios in ACA markets, a risk adjustment methodology that brings loss ratios closer together (aka “compresses”) is thought to be directionally correct. The success of any adjustments to the risk adjustment methodology can be similarly interpreted. Stated another way, if risk adjustment (and modifications to risk adjustment) improves results for poorly performing issuers and dampens results for well-performing issuers, it is generally thought to be doing a good job.

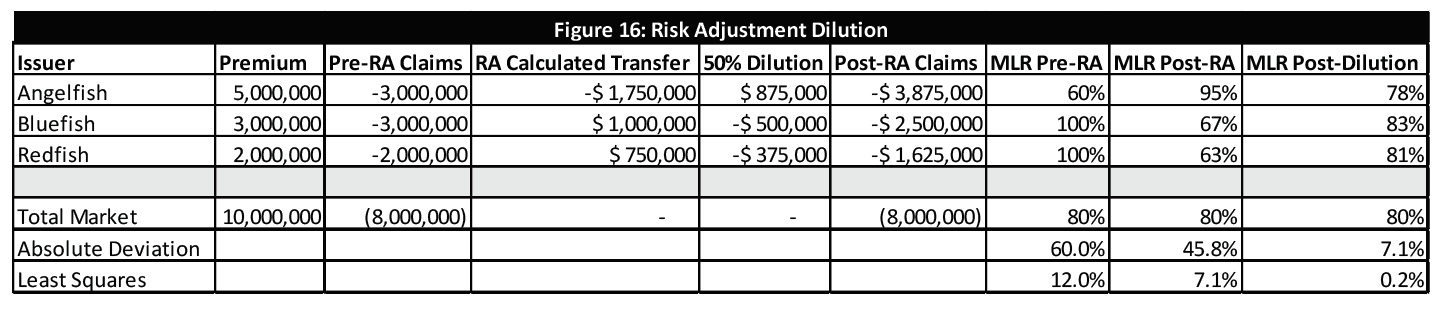

Multiple adjustments to the risk adjustment (RA) methodology, including “caps” on transfer payments, have been proposed to address unpredictable volatility and alleged inequities in ACA markets. In Figure 16, a simple example of 50% dilution[26] is modeled. After each carriers’ transfer amounts are determined, the payments are diluted by 50%. Loss ratio deviation is calculated based on pre-RA results, post-RA results, and post-dilution. Absolute Deviation and Least Squares differences are displayed in Figure 16. For both measures, the differences are reduced for both risk adjustment and the dilution modification. This suggests that while risk adjustment is a beneficial adjustment, an additional benefit is gained through the risk adjustment process. These results are not necessarily indicative of risk adjustment results or the benefits of dilution, but merely explain a process of how actuaries can measure the success of ACA risk adjustment methodology and associated modifications.

A Medicare Buy-In Option Will Increase ACA Costs

As policymakers seek to build on the ACA or pivot from it during a presidential election year, new proposals are abundant and vary in specificity levels. One popular proposal has been to allow adults as young as 50 to buy-in to Medicare; the official Democratic Party platform is age 55.[27] This is perceived to accomplish at least two goals. First, it provides an additional (and presumably more cost-effective) option for older people to obtain coverage. Second, the migration of older people out of the ACA risk pool reduces the average age and leaves the ACA risk pool younger and healthier. It can also be argued that it would reduce the average cost of Medicare enrollees.

Undoubtedly surprising to most people, a recent RAND study[28] found that allowing older adults to opt into Medicare would cause ACA premiums to increase (and reduce costs for lower-income enrollees as we learned earlier) as the ACA population would become less healthy. This is an interesting dynamic; it means that the 3:1 age slope is a steeper estimate of cost differences than actual ACA enrollment.[29] While it is generally acknowledged that the theoretical age slope is at least 5:1, “a broad variety of older adults, including both healthy and unhealthy people, tends to enroll in the individual market. Younger adults who enroll in the individual market, in contrast, tend to be unhealthy and expensive.”[30] Hence, the resulting cost difference is a measure of all older adults compared to unhealthy young adults.

While ACA architects likely believed resulting premiums would fit along the 3:1 curve, that’s not the way premiums are designed. At the consumer level, 3:1 pricing is only experienced by unsubsidized consumers. This is a shrinking minority in all ACA individual markets. For subsidized consumers, net premiums for a benchmark plan are the same for people at the same income level regardless of their age and lower for older adults than younger adults for plans priced below the benchmark.

ACA Markets Received Needed Boost But Did Not Appropriately Respond

While operational challenges dominated public discussion in the ACA’s initial years, financial challenges were lurking underneath the surface. This became evident when high premium increases emerged in 2016 and 2017 after insurers reviewed ACA market data for the first time. Additionally, insurers exiting markets and declining enrollment signaled a bleak outlook for the ACA’s future. “Obamacare Marketplaces Are in Trouble. What Can Be Done?”[31], the New York Times asked. Insurer financial performance improved in 2017 (82% MLR compared to 99% average from 2014-2016[32]), but enrollment continued to decline and insurers continued to exit markets; many insurers were aggressively persuaded by states to remain to avoid counties without any insurers.

Throughout 2017, amidst partisan ACA repeal efforts, there were bipartisan calls to appropriate funding of Cost-Sharing Reduction (CSR) payments, which had been allowed by the Obama and Trump administrations but never officially appropriated by Congress. This bipartisan legislation was often regarded as the primary requirement necessary to “stabilize the market.”[33] The opposite was actually true.[34]

Following a legal recommendation from the Department of Justice, President Trump discontinued CSR funding in October 2017. As projected[35] by technical experts but not initially recognized by the general public, insurers responded by increasing silver premiums (colloquially “silver loading”), thereby increasing premium subsidies and reducing net premiums. As Stan Dorn notes on a Health Affairs blog, “President Donald Trump’s termination of federal cost-sharing reduction (CSR) payments in late 2017 had unexpected effects…provided increased financial assistance to many low- and moderate-income families.”[36]

The results that followed caught many observers by surprise largely because the mathematical dynamics were not understood. The higher subsidies “let consumers buy coverage other than the benchmark at a lower net premium cost, increasing enrollment and making the market more attractive to consumers and insurers alike.”[37] Enrollment significantly exceeded expectations in 2018, insurer profitability skyrocketed to record levels, and premiums decreasedin 2019 and 2020. The beneficial market changes reignited insurer interest, and the number of state-levels insurersincreased in 2019 and 2020 after reductions in 2017 and 2018.

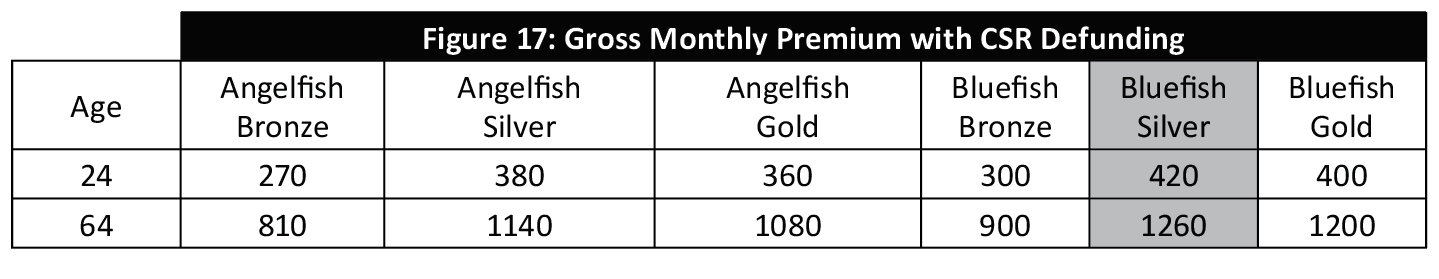

Figure 17 illustrates the “silver loading” impact on gross premiums due to CSR defunding. Figure 17 is identical to Figure 1, except Silver premiums have been loaded to account for CSR reimbursements not being paid.

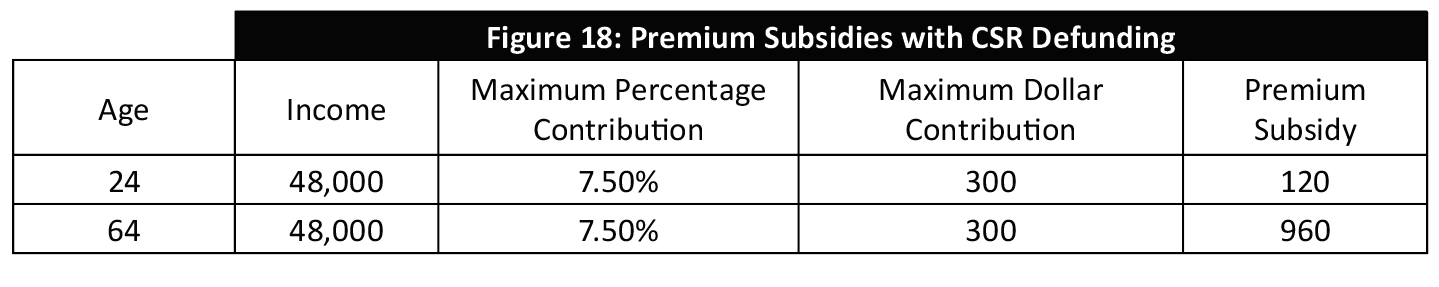

Figure 18 is identical to Figure 2, except the subsidies are higher which reflected the loaded Silver premiums.

Figure 19 illustrates the net monthly premiums with CSR defunding. Notably, Bronze premiums are free for older individuals and Gold premiums are lower than Silver premiums. Relative to other metal levels, Silver plans provide poor value to enrollees who are not eligible for CSR payments after CSR defunding.

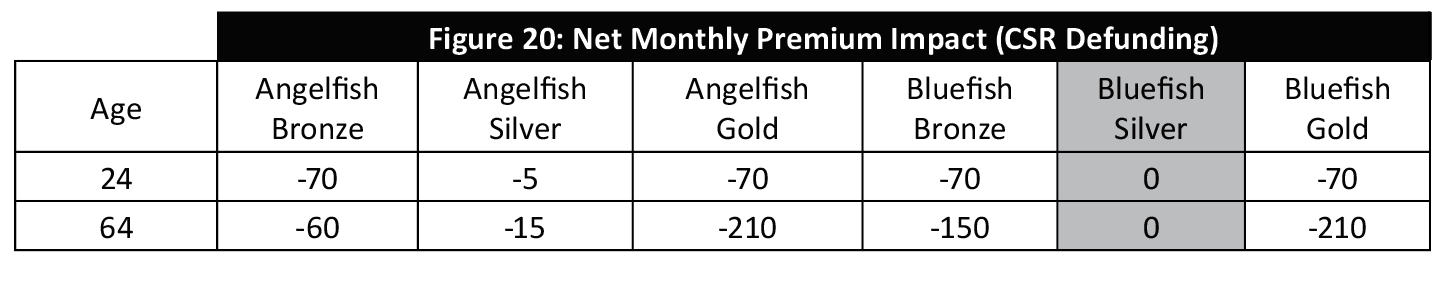

Figure 20 illustrates the net premium impact of CSR defunding. Significant savings result for Bronze and Gold plans and mild savings result for the lowest cost silver plan.

Market Response Reflects Conflicting Incentives

An expected market response indicative of Figure 19 results would suggest low cost of free Bronze plan options and reasonably valued (below Silver) Gold[38] plans. From 2018 to 2020, most state markets have not responded in this way. An understanding of ACA rules, insurer incentives. and the state regulatory environments provide some clarity.

Of the four benefit/metal levels (bronze, silver, gold and platinum) in ACA markets, ACA architects decided to select one level to drive two important subsidy mechanisms. As discussed, Silver was select to determine premium subsidies. Silver was also selected to serve as the base benefit for CSR enrollees (individuals eligible for CSR benefits). Fortunately for taxpayers but unfortunately for ACA consumers, the same metal level was selected for both mechanisms.

As the individual market is extremely price-sensitive, insurers are advantaged by the ability to increase silver premiums and enhance premium subsidies while not having corresponding increases at other metal levels. The conflict arises with CSR enrollees, who must select a Silver plan to obtain CSR benefits. This is a large and profitable block of business and it represents the lowest income, most price-sensitive consumers in the market. Insurers compete fiercely at the Silver level and often offset aggressive Silver premiums with excessive premiums at other metal levels. The results of these dynamics are negatively two-fold; higher premiums for non-CSR enrollees in non-silver plans (should avoid loaded Silver plans) and compressed premium subsidies due to lower Silver premiums. Of the 51 markets in 2020, 40 have still not responded appropriately by raising Silver premiums above Gold premiums.[39] This result is higher net premiums for low-income consumers and weakened markets.

In June, one commentator noted it would take several years[40] for the market to reach the ideal equilibrium. This is due to non-CSR enrollees remaining in Silver plans that provide lower benefits, have loaded premiums due to higher concentration of CSR enrollees, and yet remain priced lower than Gold plans. There are two reasons for this, the first being the hyper-aggressively priced Silver premiums to compete for CSR enrollees. The second is the automatic re-enrollment[41] process that allows enrollees to remain on their current plans without reviewing new options and taking action. The stagnation of non-CSR enrollees in Silver plans lowers the average Silver benefits and keeps Silver prices low. Over time, the migration of non-CSR enrollees away from Silver will lead to a larger concentration of CSR enrollees and higher Silver premiums and premium subsidies. After the initial movement in 2018, the expected migration has been sluggish. In October, the same commentator noted that the pricing direction actually reversed in 2020.[42]

With three years of stagnation, it appears that unregulated markets will not solve problems on their own. State regulators have the authority to require adherence to ACA guidance. A detailed review of some insurer filings and a cursory review of nationwide premiums suggest that insurers are taking the liberty to violate ACA’s anti-discriminatory requirements which require consistently developed premium rates from a standard population. This allows specifically targeted competition with some benefit plans rather than objective, appropriate pricing relationships. As discussed, this disadvantages consumers and markets. While state regulators are attuned to gross premium changes (we learned lower premiums actually require many consumers to pay more) which appear in the local newspaper, evidence suggests that there is less enforcement of appropriate premium alignment which has a greater impact on consumer net premiums. The rationale for a relaxed regulatory environment[43] was understandable a few years ago, but the improved federal market environment needs the help of states to bring the federal action to full fruition. The problem can be corrected in 2021, but it will require the swallowing of a red pill by blue states and red states alike.

Conclusion

Proclamations that “markets need healthy competition and innovations that reduce systematic costs” do not generally warrant objection. As we approach the ACA’s 10th anniversary, these vanilla-flavored viewpoints, which directly conflict with the ACA design, are still being expressed as viable ACA solutions. We can no longer idly pretend ACA individual markets function like other health care markets and the solutions are similar; it is a disservice to those who lack the technical inclination to comprehend the convoluted system.

There is much we know and much we have learned in the last 10 years. We know that the ACA’s federal financial commitment provides some individuals with new opportunities to enroll in individual markets. We have learned that the ACA is full of counterintuitive dynamics and perverse incentives. Reducing premiums results in higher costs for low-income enrollees.

We know that competition provides more choices and lower gross premiums. We have learned that competition harms ACA markets. We have learned that some state exchanges do not want some insurers in their markets because their costs are too low. That is worthy of repeating: some state exchanges do not want some insurers in their markets because their costs are too low.

We know that ACA markets need young and healthy individuals to enroll, while we have learned that a system has been designed that provides both enrollment disincentives for young eligible enrollees and penalties for insurers who enroll them.

We know that ACA markets received a needed boost through enhanced premium subsidies resulting from CSR-defunding in 2018. We have learned that insurers have not fully responded to the improved market opportunity due to selective competitive reasons, and rate regulation to properly align pricing factors have not been widely enforced.

We know that the structural ACA design is extremely inefficient, resulting in a cost of about $17,000 annually for each incremental enrollee. As it exists today, the ACA requires some unacceptable tradeoffs and ties their hands outside of Section 1332 waivers. Cost reductions should never penalize consumers, and that is the reality today. Income gains[44] should never penalize consumers either.

After years of disadvantages relative to group markets, the new financial commitment to the individual market is substantial and should allow it to flourish. Instead, rules have been designed and subsidies have been allocated in an illogical manner such that enrollment is skewed and the mathematical dynamics are peculiar. Markets will not be further improved unless we engage in a serious understanding of ACA dynamics. Since inception, the only improvements that have made the ACA consumer experience better were disparaged as harmful, the legal challenge that led to CSR subsidies being voided and increased premium subsidies and the repeal of the individual mandate penalty leading to more flexible consumer options. In a recent survey, Kaiser Family Foundation reports that “Since 2016, More People Say the ACA Has Helped Them or Their Families, Fewer Say It Has Hurt”.[45] While recent regulatory action has helped, the ACA still has inherent challenges. A willingness to acknowledge the convoluted ACA dynamics and boldness to take appropriate steps will result in stronger markets across the country.

Improving the ACA requires a dispassionate understanding of the underlying mechanics and mathematical ramifications. The ACA is challenged because these mechanics have not been well understood. Coming to terms with the truth of the ACA’s non-intuitive dynamics may indeed be unpleasant, but it’s a pill we are going to need to swallow if we are serious about improving the law’s ability to fully serve the population it was originally intended to serve.

Endnotes

[1] Fann G. Implications of Individual Subsidies in the Affordable Care Act—What Stakeholders Need to Understand. Health Watch. May 2014. https://www.soa.org/globalassets/assets/Library/Newsletters/Health-Watch-Newsletter/2014/may/hsn-2014-iss-75.pdf

[2] The Matrix: The Pill Scene (with English Sub). Youtube. https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=blue+pill+scene+matrix&view=detail&mid=AD94B8BC53DB55B0478DAD94B8BC53DB55B0478D&FORM=VIRE

[3] Fann G. Annual Ranking of the ACA’s First Decade. In The Public Interest. July 2019. https://sections.soa.org/publication/?m=58953&i=601450&view=articleBrowser&article_id=3426992

[4] Despite deliberate talking points from both sides leading Americans to believe otherwise, legislative repeal of the ACA has not been a serious threat since President Trump’s private comments were leaked after the American Health Care Act passed and the Senate followed with proposals that were based on the ACA model.

Trump calls House healthcare bill ‘mean’ during closed-door meeting with senators ‒ report. RT. June 14, 2017. https://www.rt.com/usa/392140-trump-ahca-mean-sources/ Accessed January 14, 2020.

[5] Fann G. The Sustainability of the New American Entitlement: Actuarial Values and the ACA. In The Public Interest. September 2016. https://www.soa.org/globalassets/assets/Library/Newsletters/In-Public-Interest/2016/september/ipi-2016-iss13.pdf

[6] Schumer Remarks on President Trump Ending CSR Payments. Senate Democrats Newsroom. https://www.democrats.senate.gov/news/press-releases/schumer-remarks-on-president-trump-ending-csr-payments

[7] Fann G. Separating Politics from Policy. LinkedIn Pulse. November 1, 2019 https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/separating-politics-from-policy-greg-fann/

[8] Wilson DJ. The benefits of Trump’s CSR decision. Alaska Journal. October 16, 2017.

https://www.alaskajournal.com/2017-10-16/guest-commentary-benefits-trump’s-csr-decision/#_.WebbomgpCaO Accessed January 14,2020.

[9] Anderson D, Sprung A, Drake C. ACA Marketplace Plan Affordability Is Likely To Decrease For Subsidized Enrollees In 2020. Health Affairs. November 22, 2019. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20191118.253219/full/ Accessed January 14,2020.

[10] Fann, G. Lower Premiums in 2019 ACA Markets: What’s the Actuarial Explanation? In the Public Interest, January 2019, https://sections.soa.org/publication/?i=556458&p=&pn=#{“issue_id”:556458,”view”:”articleBrowser”,”article_id”:”3279809″}

[11] Walker J. “Fixing” the ACA Exchanges Only Makes Them Worse. People’s Policy Project. April 4, 2018 https://www.peoplespolicyproject.org/2018/04/04/fixing-the-aca-exchanges-only-makes-them-worse/ Accessed January 14,2020.

[12] Fann G. New Section 1332 Flexibility: State Relief and Empowerment Waiver Opportunities. Axene Health Partners, https://axenehp.com/new-section-1332-flexibility-state-relief-empowerment-waiver-opportunities

[13] Fann G. Putting the ACA Back Together Again. The Actuary, February 2019, https://theactuarymagazine.org/putting-the-aca-back-together-again

[14] Fann G. Obamacare’s Unlikely Savior. Axene Health Partners. https://axenehp.com/obamacares-unlikely-savior/

[15] Fann G. ACA Premium Changes: We Need a New Measuring Stick. Axene Health Partners. https://axenehp.com/aca-premium-changes-need-new-measuring-stick

[16] Fann G. The Lionfish in ACA Markets. Axene Health Partners. https://axenehp.com/lionfish-aca-markets

[17] Fann G. Making Rate Review Great Again. Axene Health Partners. https://axenehp.com/making-rate-review-great/

[18] Norris L. Rhode Island health insurance marketplace: history and news of the state’s exchange. December 16, 2019. https://www.healthinsurance.org/rhode-island-state-health-insurance-exchange/#rates Accessed January 14,2020.

[19] Fann G. Not Your Grandmother’s Risk Adjustment. The Actuary, December 2018/January 2019, https://theactuarymagazine.org/not-your-grandmothers-risk-adjustment

[20] Fann G. Annual ACA Check Up: Stabilizing the New Marketplaces. Axene Health Partners. https://axenehp.com/annual-aca-check-stabilizing-new-marketplaces/

[21] Christopherson A. Market Dynamics Under ACA Risk Adjustment. The Actuary. https://theactuarymagazine.org/market-dynamics-aca-risk-adjustment/ Accessed January 14,2020.

[22] Brockman S. Transfer Problems. The Actuary. https://theactuarymagazine.org/transfer-problems/ Accessed January 14,2020.

[23] Brockman S. Transfer Problems. The Actuary. https://theactuarymagazine.org/transfer-problems/ Accessed January 14,2020.

[24] Foster R. Method to Address Estimation Bias in the HHS-HCC Risk Adjustment Model—Memorandum to CHOICES Executive Committee. CHOICES: Consumers for Health Options, Insurance Coverage in Exchanges in States. July 15, 2016. http://www.stevannikolic.com/documents/CHOICESWhitePaperonRiskAdjustment.pdf Accessed October 1, 2018.

[25] Insights on the ACA Risk Adjustment Program. American Academy of Actuaries. April 2016. https://www.actuary.org/sites/default/files/files/imce/Insights_on_the_ACA_Risk_Adjustment_Program.pdf

[26] While states have proposed various adjustments to promote equity, the only federal guidance is in the 2019 and 2020 Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters (annual regulation establishing and updating ACA market rules). With approval, states are allow to dilute risk adjustments up to 50%. In 2020, Alabama received approval to adjust small group market payments by 50%.

[27] https://democrats.org/where-we-stand/party-platform/ensure-the-health-and-safety-of-all-americans/

[28] Eibner C, Vardavas R, Nowak S, Liu J, Rao P. Opening Medicare to Americans Aged 50 to 64 Would Cut Their Insurance Costs, but Drive Up Insurance Prices for Younger People. RAND Corporation. November 18, 2019. https://www.rand.org/news/press/2019/11/18.html Accessed January 14,2020.

[29] Fann G. Another ACA Paradox: Lowering the Average Age Increases Premiums. LinkedIn Pulse, November 18, 2019, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/another-aca-paradox-lowering-average-age-increases-premiums-greg-fann

[30] Eibner C, Vardavas R, Nowak S, Liu J, Rao P. Opening Medicare to Americans Aged 50 to 64 Would Cut Their Insurance Costs, but Drive Up Insurance Prices for Younger People. RAND Corporation. November 18, 2019. https://www.rand.org/news/press/2019/11/18.html Accessed January 14,2020.

[31] Abelson R, Sanger-Katz M. Obamacare Marketplaces Are in Trouble. What Can Be Done?. The New York Times. August 29, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/30/upshot/obamacare-marketplaces-are-in-trouble-what-can-be-done.html Accessed January 14, 2020.

[32] Cox C, Fehr R, Levitt L. Individual Insurance Market Performance in 2018. Kaiser Family Foundation. May 7, 2019. https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/individual-insurance-market-performance-in-2018/ Accessed January 14,2020.

[33] Shaw G. Senate ACA stabilization hearings: State insurance commissioners talk reinsurance, CSR payments. FierceHealthcare. September 6, 2017. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/aca/senate-help-aca-hearing-state-commissioners-reinsurance-csr Accessed January 14,2020.

[34] Fann G. The Cost-sharing Reduction Paradox: Defunding Would Help ACA Markets, Not Make Them Implode. Axene Health Partners, https://axenehp.com/cost-sharing-reduction-paradox-defunding-help-aca-markets-not-make-implode

[35] Hall K. The Effects of Terminating Payments for Cost-Sharing Reductions. Congressional Budget Office. August 2017. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/reports/53009-costsharingreductions.pdf Accessed January 14,2020.

[36] Dorn, S. There’s No Pain-Free Way To Get Beyond Silver Loading. Health Affairs. September 10, 2019. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190828.76145/full/ Accessed January 14,2020.

[37] Dorn S. There’s No Pain-Free Way To Get Beyond Silver Loading. Health Affairs. September 10, 2019. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190828.76145/full/ Accessed January 14,2020.

[38] Fann G. Fields of Gold. Axene Health Partners. https://axenehp.com/fields-of-gold/

[39] Cruz D. The Gold Rush and the Lionfish: Optimizing the Unique Dynamics in ACA Markets. Axene Health Partners. https://axenehp.com/gold-rush-lionfish-optimizing-unique-dynamics-aca-markets/

[40] Sprung A. Silver loading is just getting started. Xpostfactoid. June 5, 2019. https://xpostfactoid.blogspot.com/2019/06/silver-loading-is-just-getting-started.html

[41] Fann G. Risk Adjustment State Flexibility, Silver Loading and Automatic Re-enrollment. Linked Pulse. April 19, 2019. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/risk-adjustment-state-flexibility-silver-loading-automatic-greg-fann/

[42] Sprung A. Silver loading goes into reverse in 2020. Xpostfactoid. October 24, 2019. https://xpostfactoid.blogspot.com/2019/10/silver-loading-goes-into-reverse-in-2020.html

[43] Fann G. Making Rate Review Again. Axene Health Partners https://axenehp.com/making-rate-review-great/

[44] Not discussed in this paper, but a major concern.

[45] Since 2016, More People Say the ACA Has Helped Them or Their Families, Fewer Say It Has Hurt. Kaiser Family Foundation. February 19, 2020. https://www.kff.org/other/slide/since-2016-more-people-say-the-aca-has-helped-them-or-their-families-fewer-say-it-has-hurt/

About the Author

Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.