“If you think health care is expensive now—just wait until it’s free.”

—P.J. O’Rourke

Health care is expensive in the United States. If you have paid attention to the Society of Actuaries Health Section since 2018, you are familiar with Initiative 18/11. The catchy title derives from the fact that health care spending is 18 percent of the United States’ Gross Domestic Product compared to 11 percent in similar countries. The initiative is intended to close that gap; it’s a long-term goal and it’s a real challenge.

While most of the recent health policy considerations have acknowledged the overarching cost problem, legislative and regulatory efforts have primarily been designed to provide financial incentives for people to be insured, further increasing the federal government’s health care spending rather than fostering efforts to reduce it. Accordingly, public finance is playing a greater role in our nation’s health care framework, and this article brings attention to a recent philosophical shift that has gone unnoticed largely because it has been uncoordinated. We begin this discussion with a review of the underlying policy background and conclude with the recent changes implemented amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

The ACA Parlay

The most prominent health policy change in the past 50 years was the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Act (ACA) in 2010. The ACA was a broad law, but its primary goal was to reduce the uninsured rate and it attempted to do so through two separate financial mechanisms.

The first mechanism was encouraging states to expand Medicaid by offering a higher federal matching rate for the newly eligible population, one based solely on income rather than also including another qualifying condition. 38 states have accepted this offer, while some of the other 12 states are considering it.

The second mechanism was the restructuring of the individual health insurance marketplace and new federal funding to subsidize coverage for some enrollees. The subsidization process is convoluted and unbalanced, resulting in generous subsidies for some individuals and no subsidies to offset exorbitant premiums for others.

The ACA‘s success in reducing the uninsured rate has been mixed. About 20 million more people are enrolled in Medicaid due to states accepting the expansion option. While the new private insurance market subsidies amount to about $54 billion each year, there has been little impact on the uninsured rate from the private insurance market. In fact, private insurance enrollment was lower in 2018 than it was in 2009, the year before the ACA passed.

The significant enrollment shortfall, insurers losing money and fleeing markets, and a steady stream of large annual premium increases led to the law’s viability concerns in 2016. The election of President Trump signaled a likely change to a different framework designed to be more efficient and sustainable.

The Trump Bump

After Republican “repeal and replace” legislative efforts failed, the Trump administration implemented a series of regulatory changes that altered ACA market dynamics. Consumer affordability improved, new flexibility was granted to consumers and states, the law’s popularity grew, and urgency to chart a new legislative course subsided.

The Trump administration inherited the traditional ACA environment, where the primary differential indicators of ACA consumer value were two-dimensional, age and income. The ACA was designed to benefit older and lower-income individuals. As actions of the Trump and Biden administrations are more transparently interpreted through an income rather than an age lens, this article provides a one-dimensional, income-stratified view of the changing landscape for health insurance consumers.

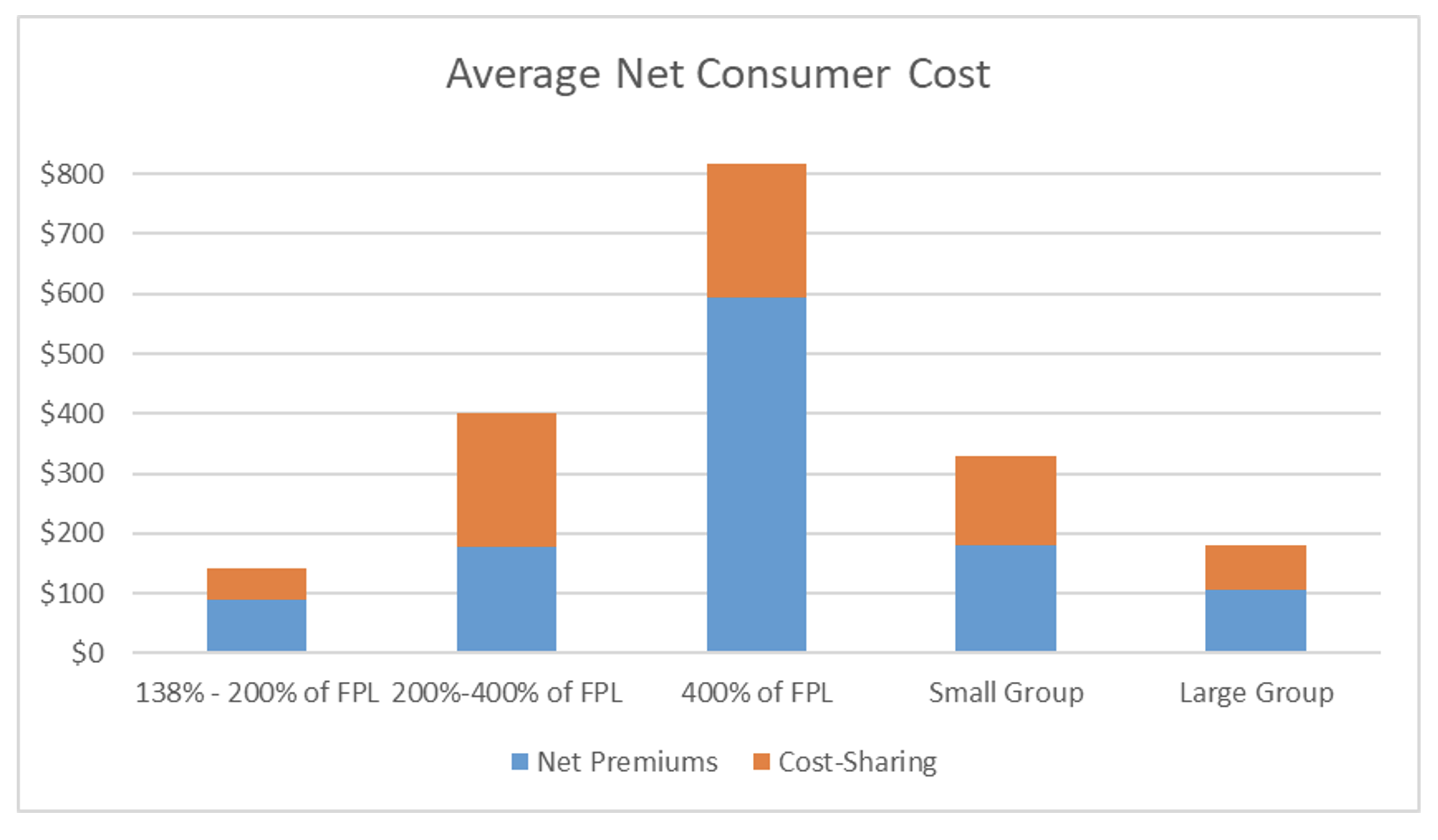

Figure 1

Average Monthly Net Consumer Costs in Commercial Markets with ACA

The ACA’s income-based consumer value proposition is easy to understand. Figure 1 displays net premium costs and cost-sharing (copays, deductibles, etc.) that consumers are required to pay net of third-party (employer or government) contributions. As the group insurance markets are extensive and familiar, they represent a plausible benchmark as a comparison to individual market costs. Large Group employers generally contribute a greater share of premiums and provide more generous benefits than small employers. Comparability with Small Group insurance may be a more reasonable goalpost for assessing individual market attractiveness, and that measure is assumed for the purposes of this article.

Using Small Group costs as a benchmark, the ACA individual market was originally attractive to individuals with incomes above the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) and below 200 percent of FPL, less attractive for individuals with income between 200 percent and 400 percent of the FPL, and severely unattractive for individuals with incomes above 400 percent of the FPL.

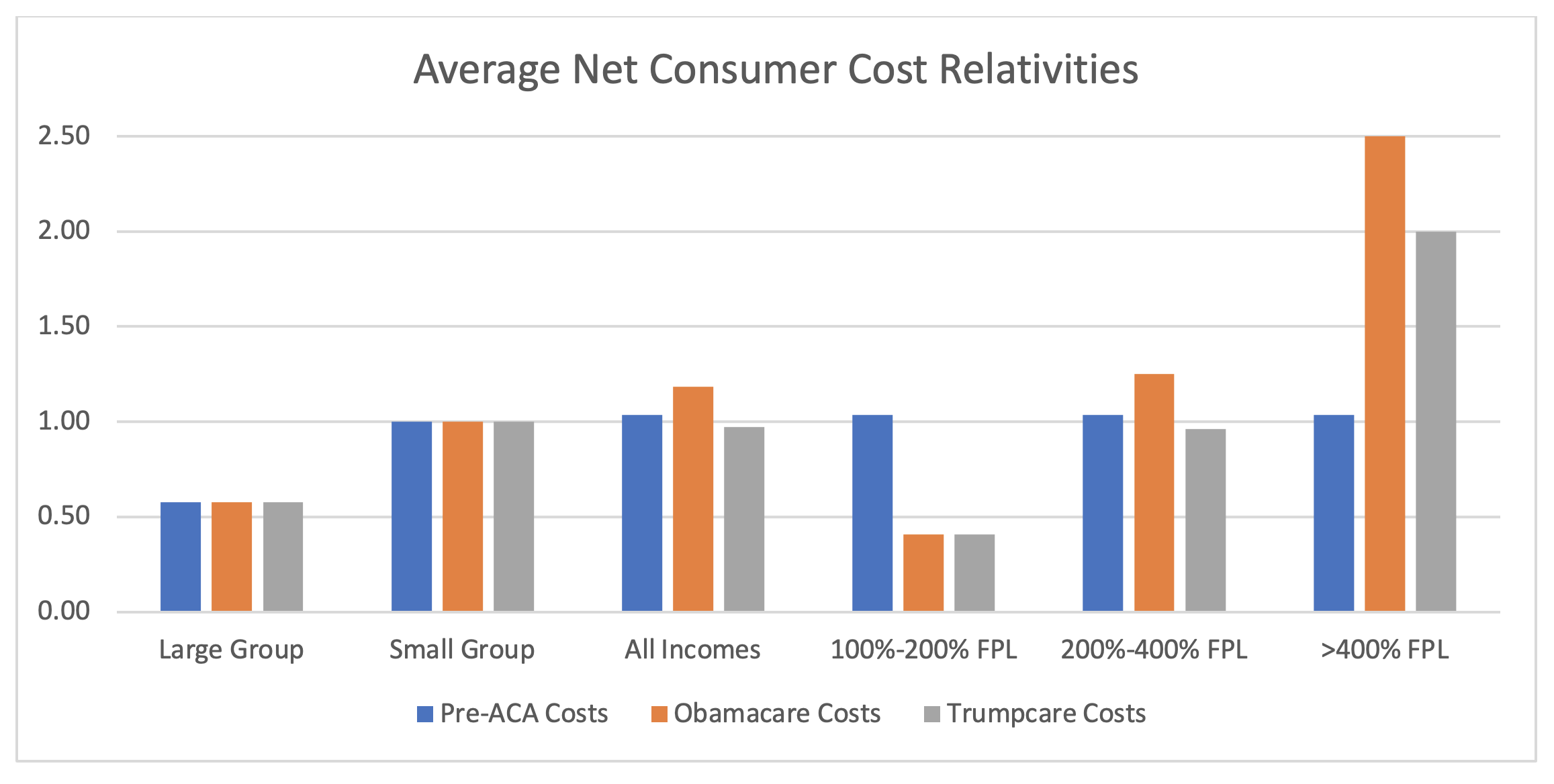

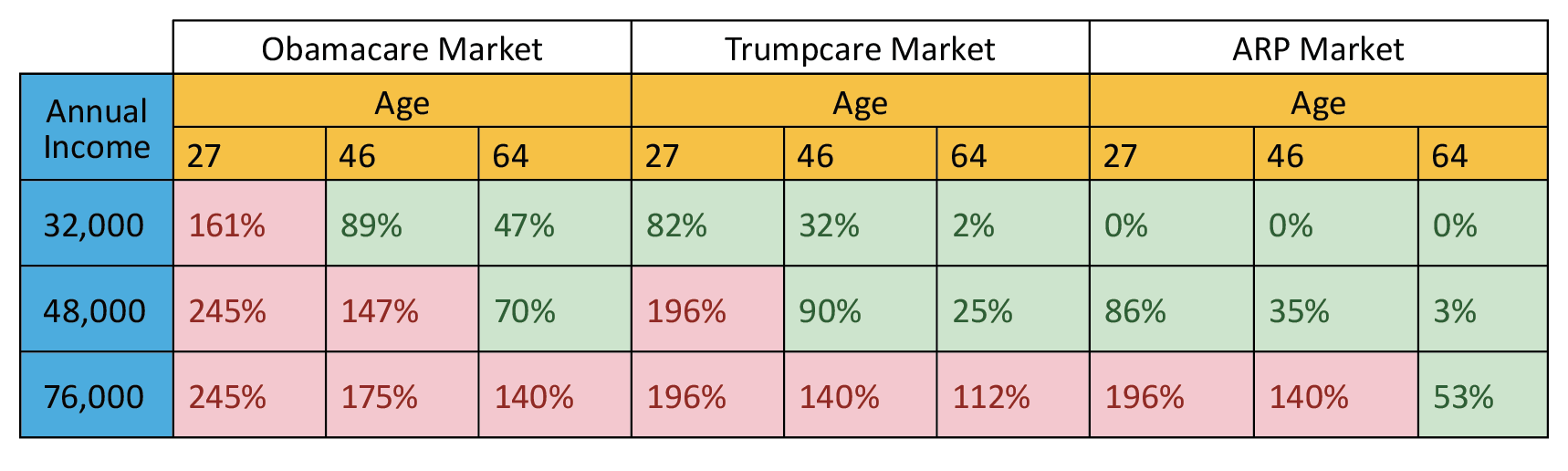

The Trump administration’s actions directly reduced premium costs for the population with incomes between 200 percent and 400 percent of the FPL, specifically by recalibrating the benchmark plan from a silver level to a platinum level. The consequential impact has been more attractive premiums, primarily for young, healthy individuals in this income cohort who are the most likely to be uninsured. Indirectly, gross premium rates have been flat for three years and unsubsidized enrollees (incomes greater than 400 percent of the FPL) have also benefited, albeit at still unattractive premium rates. Figure 2 illustrates the comparative market costs relative to Small Group with “Obamacare” representing the 2016 environment and “Trumpcare” representing the 2018 environment after the regulatory changes were implemented.

Figure 2

Average Net Consumer Cost Relativities in ACA Policy Environments

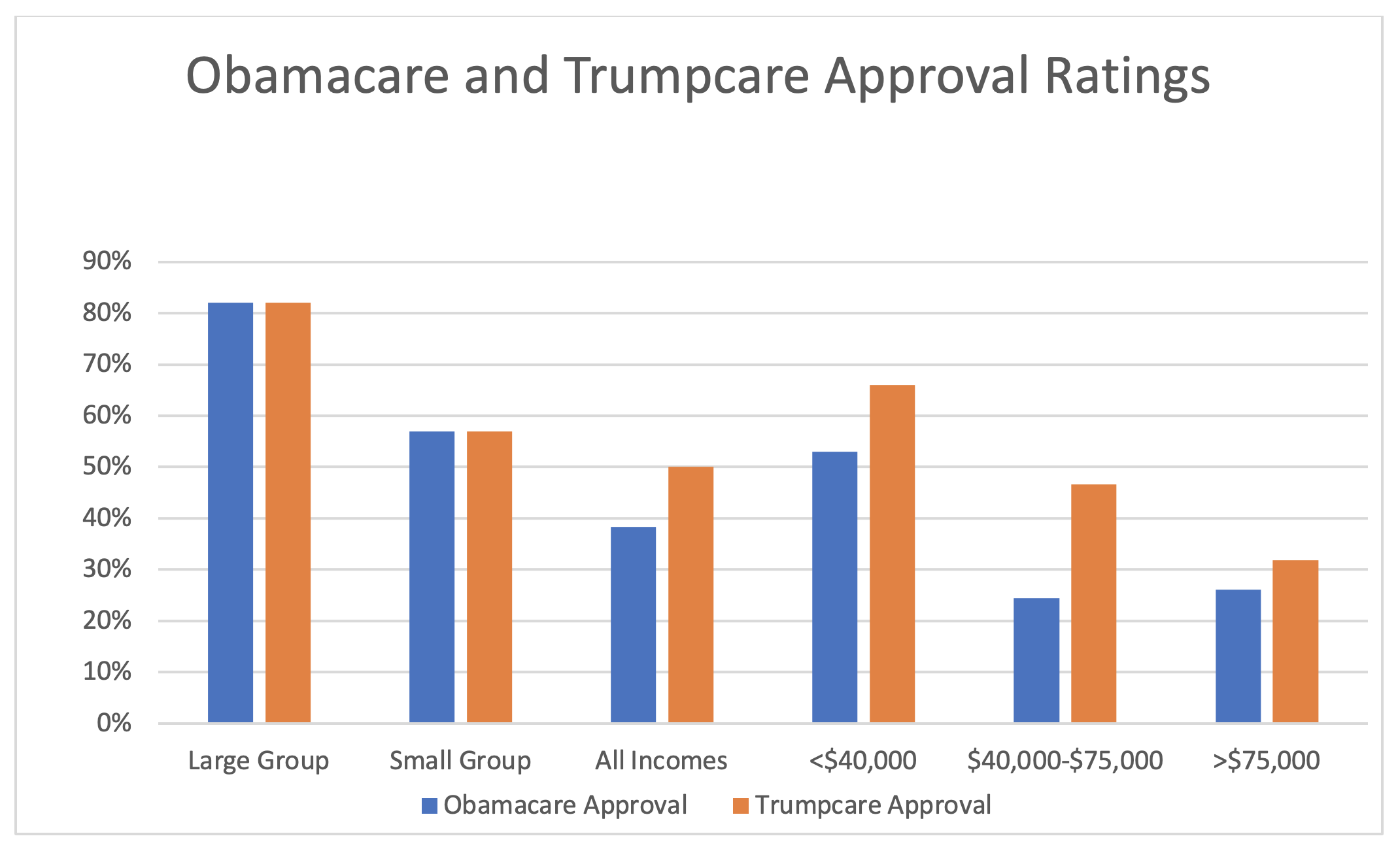

Subsidized enrollment declined in 2017 but rose in 2018 and 2019 as the market became attractive for the 200–400 percent FPL cohort. In 2020, on-exchange unsubsidized enrollment (>400% FPL) increased for the first time since ACA implementation. While the Trump administration’s collective actions have contained ACA premium levels, the high premium rates remain unattractive, and the larger contribution for this income cohort was the elimination of the individual mandate penalty and the expansion of non-ACA compliant options. It is noteworthy that ACA markets are now viewed with greater favorability in all income segments, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Consumer Approval Ratings in ACA Policy Environments

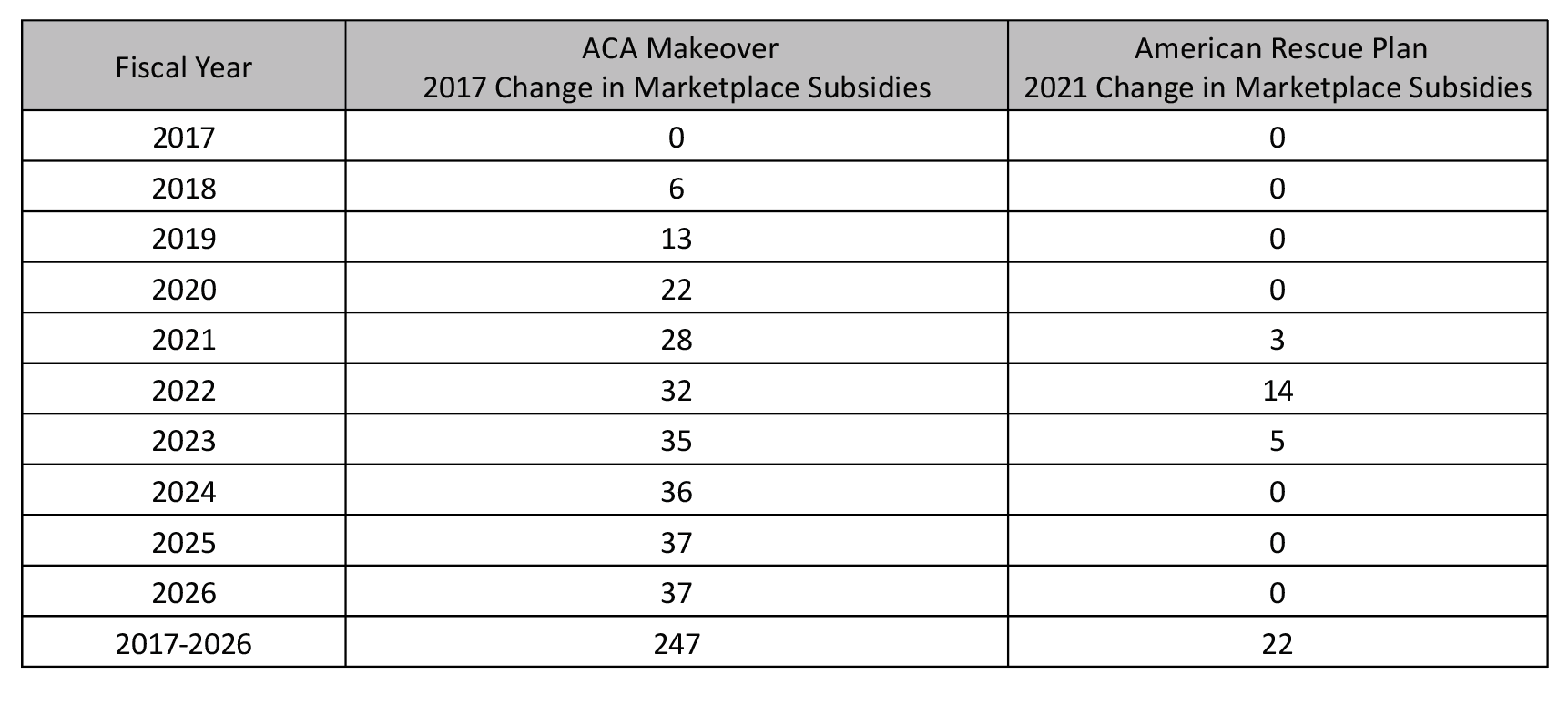

Amidst an improved ACA market environment, the election of President Biden clarified one future direction and added mystery to another. The clear direction was more government involvement in the nation’s health care system, financial and otherwise. The mystery is whether continued subsidy enhancements (beginning in 2018) in ACA markets will remain the continued focus versus a pivot to more government-centric options that would poach ACA enrollees (e.g., public option, reduction in Medicare age eligibility). In the first, but likely not the last, related health legislation from the Biden administration, it has been the former.Specifically, the legislation put forth temporary parameter changes on top of the Trump administration’s developing but market-challenged enhancements that are scheduled to grow in each year of the Biden presidency. Table 1 displays the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projections of ACA subsidy enhancements due to defunding of CSR payments and Section 9661 in the American Rescue Plan (ARP).

Table 1

ACA Premium Subsidy Enhancements (billions of dollars)

The Pandemic Alchemic

Has it resonated what has happened to health insurance markets over the past year? Various groups of people now have access to generous benefits with no premium contributions required of individual enrollees. Have you noticed? You may not have, because it has been incremental and disconnected. Overall, the health insurance landscape has been transformed in a disjointed fashion by new federal contributions with COVID-19 providing a rationale. It is worthwhile to list each of them and understand their distinctions.

- Medicaid continuation under Public Health Emergency [until end of the quarter when the national emergency status is lifted].

In exchange for an additional 6.2 percent in their federal matching rates, states cannot terminate most Medicaid enrollees whose eligibility expires during the public health emergency (PHE). Millions of additional people remain enrolled in premium-free Medicaid programs due to this provision.

- Free ACA coverage for benchmark silver plan for everyone below 150 percent of FPL (94 percent actuarial value plan) [until end of 2022].

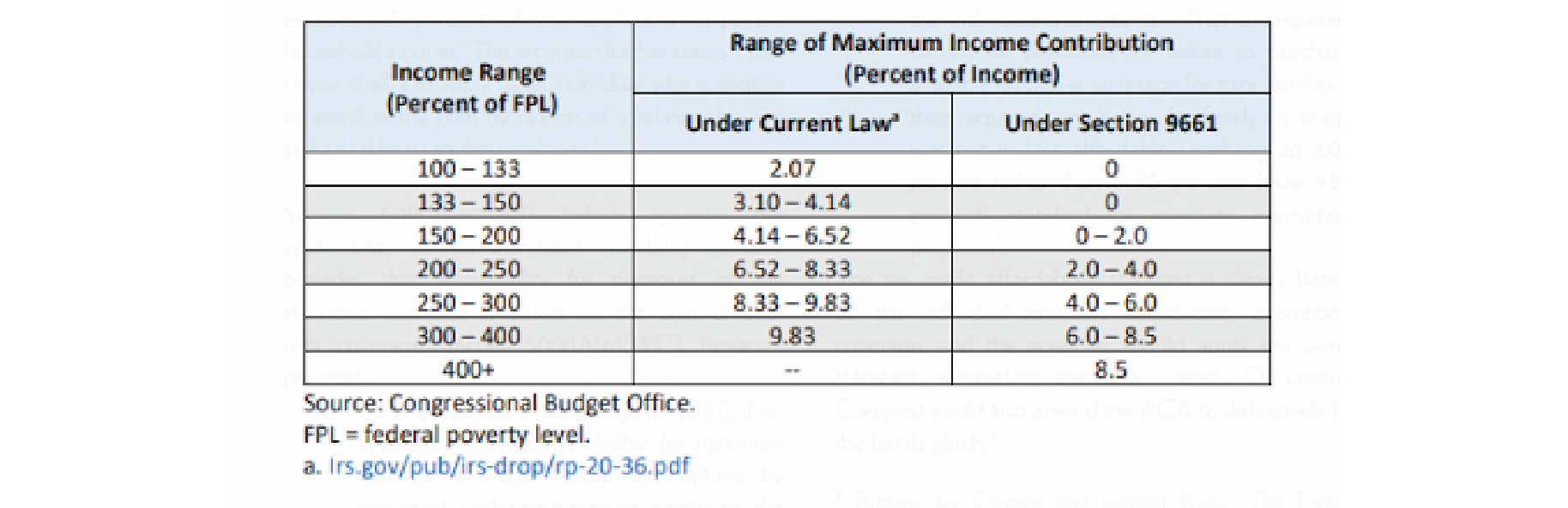

The ARP changes the ACA’s subsidy parameters temporarily. Anyone with an income less than 150 percent of the FPL can select the benchmark plan (second lowest-cost silver plan in the county of residence) or the lowest-cost silver plan for free. Previously, they would have to pay 2.07 percent to 4.14 percent of their income to procure the benchmark plan. Notably, this population is eligible for generous cost-sharing subsidies that are only available with a silver plan selection. Table 2 displays the ARP’s Section 9961 impact on contribution ranges.

Table 2

American Rescue Plan Premium Contribution Scale

- Free ACA coverage for many more people in non-silver plans through ARP parameter enhancements. (ARP enhancements through 2022, ACA makeover permanent)

The Trump administration’s ACA makeover has been slow developing, but significant changes occurred in 2021 (and expected in some mountain states in 2022) that made ACA markets more attractive. There are wide market variations at play here, but free gold coverage, once a novelty outlier, is now available in many states. The 8.5 percent of income limitation has been widely communicated, but that is representative of the “benchmark silver plan,” not the plans people actually buy that may be more generous than silver and free to enrollees.

- Free ACA coverage for anyone receiving unemployment benefits anytime in 2021—deemed to have an income of 133 percent of FPL. (until end of 2021).

A unique provision in the ARP is that anyone who receives unemployment benefits in 2021 is deemed to have an income of 133 percent of FPL, qualifying them for the free platinum level coverage discussed in item 2.

- One hundred percent COBRA subsidies. (through September 2021)

The ACA was designed to provide individual market coverage opportunities for Americans who lost employer-provided coverage, and it certainly provides more incentives with all the free and near free coverage now available. Apparently, that did not provide lawmakers enough comfort.

Through September, employees and dependents who lose group health coverage can remain on their group health plan with taxpayers picking up the entire cost. Normally, COBRA enrollees pay the entire cost. The original ARP legislation included 85 percent reimbursement, but it was later increased to 100 percent.

- Generally unlimited forgiveness for underestimating income to qualify for greater advanced tax credits (through the end of 2021).

If the idea of purchasing health insurance on your own strikes you as complicated and arduous, that’s likely true on its own merits. Today’s individual market consumers not only have to select a benefit plan, but also must submit a valid estimate of their future income to a state exchange or a representative handling their insurance application. If this strikes you as invasive, you understand the process.

The rationale for income estimation is that premium subsidies are effectively income-based tax credits. A consumer’s net premiums are determined based on their personal estimate of their income. As you might suspect, this all gets reconciled with actual income during annual tax filings. However, there has historically been forgiveness for those who underestimated their income and received premium subsidies in excess of what their true income would facilitate.

During the pandemic and the uncertain economic environment with high unemployment, there has been recognition that income estimation is extremely difficult for many people whose work schedules and compensation have been interrupted. Consequently, the government has been more lenient and hesitant to recover tax credits from individuals who underestimated their income during uncertain times. This has enabled more people to access free health insurance coverage without facing a future tax penalty.

Table 3 illustrates age-based, gold-level premium costs relative to the pre-ACA market for each policy scenario: Obamacare, Trumpcare, and the ARP. Notably, the ARP results include only the changes referenced in points 2 and 3 above. Many people have access to free coverage through the other avenues.

Table 3

Premium Costs Relative to Pre-ACA Environment

With the ARP, free premiums are available to low-income individuals and premiums are attractive to middle-income individuals and older high-income adults. As expected, the ARP had little impact on younger high-income individuals; age-based incongruence in consumer value may be addressed in future legislation. While millions of people have access to newly free coverage after the Trump administration’s subsidy enhancements and the ARP, there are still many people with unattractive coverage options, highlighting the continued imbalance of consumer value propositions under the ACA. Nevertheless, the recent array of changes birthed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a significant number of Americans with new access to free or near free coverage. This may result in transformative structural and philosophical changes in how many Americans access health coverage.

The Fiscal Pickle

Fiscally cognizant observers are asking the obvious question, “Can we afford this?” It is a reasonable inquiry. After all, the ACA was passed under the aura of “deficit neutrality,” which was needed to obtain moderate Democratic votes in the slim Democratic majority in Congress at that time. To this day, many ACA advocates still believe the ACA design was the right course, but the subsidies were simply too low due to budget constraints.

We have repeatedly enhanced subsidies and we have deleted many taxes that were put in place to achieve the deficit neutral certification. That gets us back to the question: “Can we afford this?”

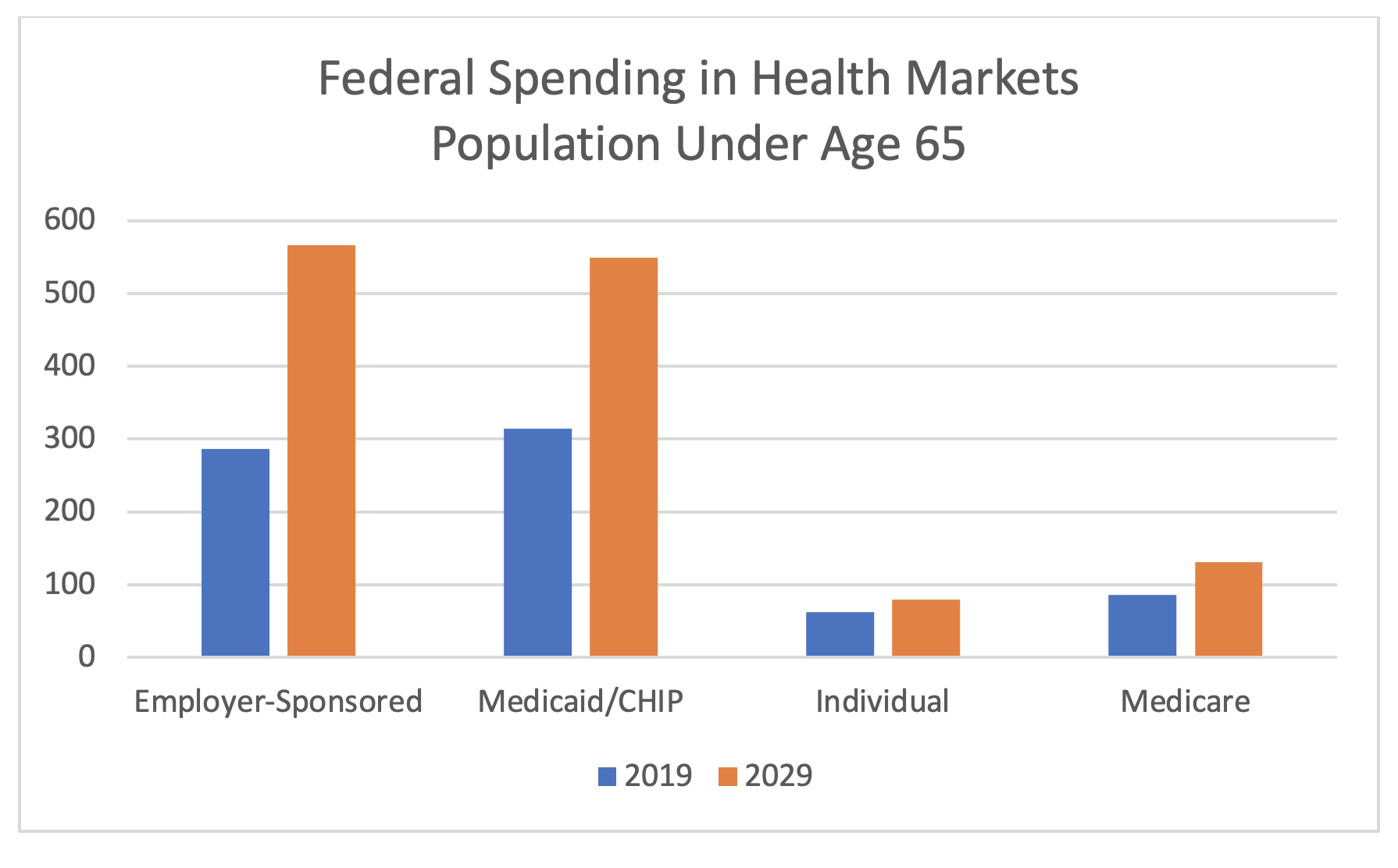

The short answer is “Yes”, at least temporarily, and the rationale is that we are still referencing a relatively small population. It is an incredibly inefficient way to fund health care, but it is the last resort for preventing a limited group of people (notably about 35% of projected size) from being uninsured. The CBO has tabulated the comparative federal annual cost of various markets and government programs for the under 65 population. The results are displayed in Figure 4. Even with a high percentage increase in individual market funding, ACA subsidy spending is still remain a fraction of total federal spending on health markets.

Figure 4

Federal Health Spending in Markets and Government Programs (billions)

The Freedom Kingdom

The ACA raised premiums and offset the impact with scattered premium subsidies, resulting in some age/income cohorts paying more and others paying less. Regulatory action by the Trump administration improved the balance by raising the base value of the benchmark plan, but younger and higher-income individuals still had to pay higher premiums than they did prior to the ACA. The ARP further enhanced premium subsidies, but it offered no relief for high-income individuals except the oldest enrollees, with subsidies declining as incomes rise. Within and outside the ARP, other changes have brought unprecedented free coverage to many people in an unorganized, disjointed fashion.

There is an underlying philosophical shift in health policy that is emerging. The ACA and the Trump administration’s enhancements were largely seen as mildly attractive markets with unbalanced financial incentives to procure coverage. The new environment offers free coverage to many people, rather than attempting to provide incentives to purchase coverage. This could be transformative; it is expected that many more people will have coverage with the new free options. It has not been broadly discussed, but this new environment could raise questions about the attractiveness and necessity of the Small Group market, shifting costs from employers to taxpayers and potentially reigniting fiscal concerns. Why would an employer continue to offer employer-sponsored coverage when other coverage is basically free to employees? In the same vein, non-ACA compliant, nongroup markets which have grown as a result of ACA unattractiveness (association health plan, short-term limited duration plans, health sharing ministries) are likely to shrink as enhanced subsidies increase the relative attractiveness of ACA markets. As a deliberate part of the ACA’s design, mandates and penalties will likely prevent the Large Group market from dissolving, but the individual market could be much larger than we expect with the transformation from coverage incentives to an undisciplined approach of making coverage free or near free on a wide scale.

When it comes to health insurance, we are now living in the land of the free. There has been no coordinated plan or no formal announcement, but many different groups of people have new access to free health insurance coverage. It remains to be seen whether this is a temporary response to a pandemic or a new permanent course. The different scenarios are extremes. One takes us back to an ACA environment with subsidized coverage but substantial premium contributions for many enrollees. The other could lead to the dissolution of small group markets in many states.

It will also be worth noticing if we continue to have millions of people uninsured with access to free coverage. This has been an uncomfortable reality with the ACA, and many more people have access to free coverage now. We simply can no longer rationalize that people are uninsured because insurance is “unaffordable.” If the uninsured rate remains stagnant, we will still have our underlying 18/11 cost problem, but we will need to face the reality that cost is not the primary rationale for explaining the uninsured rate. Health care is indeed expensive when it is free, but the societal cost of unclaimed free health care coverage may be much greater, and we will need to collectively develop solutions that extend beyond our COVID-19 response of elevated public finance.

Greg Fann is a consulting actuary at Axene Health Partners, LLC in Temecula, CA. He strategically advises clients on issues related to the ACA and is a frequent author and speaker. He is the chair of the Social Insurance & Public Finance (SIPF) Section Council of the Society of Actuaries (SOA). This article will be discussed at the SIPF Section sponsored Session 6A: A Pandemic and the ACA: Implications of the Government’s Response at the SOA Health Meeting. Presenters at this session will include Mr. Fann and Senator Bill Cassidy. The opinions expressed in this article are Mr. Fann’s alone and not necessarily reflective of his employer, the SIPF Section, or any actuarial organization.

About the Author

Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.