I came in like a wrecking ball

Yeah, I just closed my eyes and swung

– Wrecking Ball, by Miley Cyrus

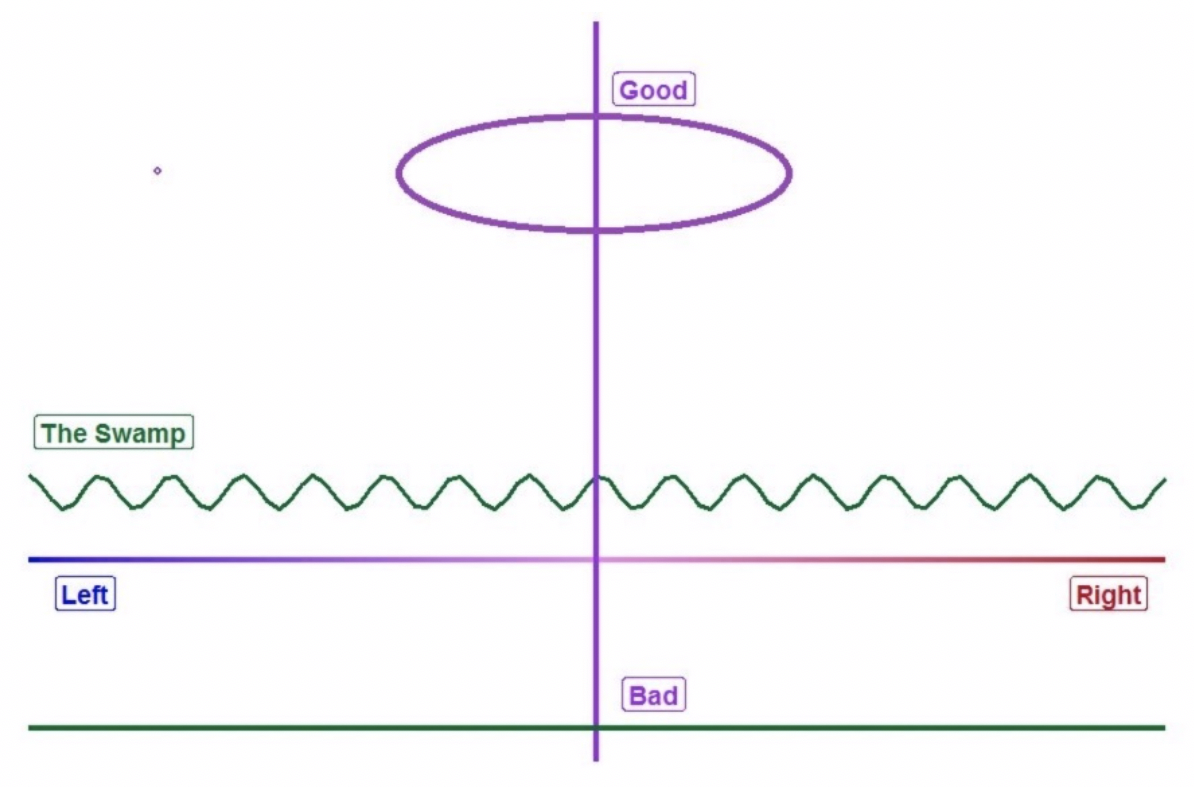

The Platinum Public Option…it’s more than just a catchy slogan. It’s a solution to coordinate the political semantics and financial dynamics of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) without disrupting fragile, price-sensitive markets. As the federal health law moves into its second decade, we can tolerate movement along the horizontal line of politics as long as we don’t slide down the vertical line of market mechanics. Recent political proposals hint at interference with the ACA’s improving dynamics and generate technical concerns. The Platinum Public Option is a solution to maintain position or move up on the vertical line while satisfying the impulses of those more focused on the horizontal.

If there are two things absent from today’s ACA markets that may have been anticipated in 2009, they are the so-called “public option” and enrollment in platinum level benefit plans. A “public option” was included in the three House bills leading up to the ACA; the House later agreed to the Senate bill that did not include a public option. Platinum benefit plans were included in the ACA’s benefit plan designs. However, they have been scarcely offered on ACA exchanges; when they are present, they are high-priced and of little interest to consumers.[1] In other words, the utilization of platinum plans for a new purpose would cause less market disruption than interference with other benefit levels. This article describes how the ACA’s two forgotten elements can be weaved together into current markets without causing significant damage.

“Public Option” Options

In the ACA environment, a public option can take two forms with important distinctions. Both forms are potentially harmful to the ACA and should be carefully developed. A public option could be offered either outside or inside of ACA exchanges.

The Public Option Act was the third House bill preceding the ACA. It allowed consumers to leave ACA markets and buy into Medicare. There is an interesting dichotomy among some ACA supporters who champion escape options for both young adults (Age 26 provision to remain on a parent’s plan) and older adults (Medicare buy-in) yet protest the allowance of other off-market alternatives (Short-term Health Plans, Association Health Plans, Health Care Sharing Ministries). Interestingly, the latter alternatives are relativity more attractive to otherwise uninsured individuals who don’t have real ACA solutions. The prior alternatives seek to attract individuals from the ACA’s core constituency and have the effect of reducing ACA enrollment.

Within the first year of implementation, it was recognized that the market was older than desired, partially due to the Age 26 provision; ACA architects thought that 39% of the market needed to be represented by the 18-34 age range to be viable; actual enrollment was only 28%. As young healthy adults avoided the ACA and a broader mix of older adults enrolled, interesting dynamics developed. A recent study determined that a Medicare Buy-In Option will increase ACA costs. As individual ACA markets will further stabilize with increased enrollment, greater employer access and less individual churn, an off-market public option would be counterproductive as “the collateral damage of a Medicare buy-in would be a shrunk, last resort, limited individual market resembling a small remnant of the robust marketplaces that ACA architects once envisioned”.

As ACA enrollment is currently less than half of its expected size and unsubsidized enrollment continues to bleed away, strengthening ACA markets is incongruent with government-supported escape options which further reduce enrollment volume. In the interest of preserving ACA markets as viable risk pools, the remainder of this article considers the public option framework to be competitive plans on ACA exchanges.

The first two House bills proposed in 2009 created exchanged-based public options. The America’s Affordable Health Choices Act and the Affordable Health Care for America Act included a public option as an exchange-based option directly competing with private insurance plans. Ten years later, state-based efforts are underway in Colorado and Washington to utilize the private marketplaces to provide access to a provider network with lower reimbursement costs. These plans have been branded as “public options”, but private insurers still manage operations and retain insurance risk. The public option concept is the same as it was in 2010, providing a seamless alternative to traditional plans at a lower cost.

It is worth noting that President Obama’s call for a public option in 2016 was limited to certain geographic regions and intended to address the specific problem of a lack of private plans. He said, “Congress should continue its work to ensure all Americans have access to affordable health coverage by adding a public option to the exchange marketplace in counties lacking competition”. Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Burwell concurred “The public option is a way that we can, in places where there is not competition, make sure that people have choice and options.” While bare markets were once a real concern, waning participation of health plans reversed after market improvements in 2018. Insurer ACA participation grew in 2019 and 2020 after reductions in the previous three years. Calls for a public option in today’s improved ACA environment are not practical solutions aimed at filling market gaps; they are philosophical in nature and intended to provide more Americans access to government-based health coverage.

Blind Ambition

Many proponents of a “public option” do not see potential harm. In their view, it is simply adding another plan option in the market. As Robert Reich explains, “That’s it. It’s that simple…not very scary or complicated at all.”. While not complicated in a natural setting, it is complicated in the paradoxical ACA world. Adding a more competitive plan to ACA markets doesn’t help them; it harms them, or at least it harms most enrollees whose incomes are low enough to qualify for premium subsidies. A lower-cost health plan offered at a metal level that determines premium subsidies would serve to reduce premium subsidies and increase consumer costs; it would be classified as a Lionfish Public Option rather than a Platinum Public Option.

The impact on the existing market should be the primary deliberation when considering a public option. Blindly adding a public option to an ACA marketplace is a lot like swinging a bat with your eyes closed. Hearing the repeated message of “building on the ACA by adding a public option” is scratching of the chalkboard to those who understand ACA math. While it has been the obligatory position of Democratic presidential candidates not seeking to repeal the ACA, a “public option” often sounds more like a ‘checkbox’ to qualify as the nominee than a serious effort to improve ACA markets.

Consumer Optimization of Metal Levels

An understanding of metal levels and current ACA dynamics is instructive to understand why a Platinum Public Option might be a viable solution. Traditionally, the selection of benefit richness has been linked to perceived health status. Those that believe they will utilize health care generally select richer benefits. Due to the unique subsidy dynamics, the incentives are much different in ACA individual markets.

The ACA’s restrictive rating rules necessarily create arbitrage opportunities. It’s beyond the scope of this article, but each benefit plan should have different age rating slopes; the ACA mandates a single rating slope for all plans.

While the market is approaching pricing alignment equilibrium slower than expected, it is clear that metal level selection eventually will be based on income level, not perceived health status. The discussion in the rest of this section matches each metal level with the income group it should attract in terms of earnings relative to the Federal Poverty Level (FPL).[2]

Bronze – Above 400% of FPL. These individuals do not any receive premium subsidies and coverage is very expensive. The cost-sharing for any medical services is usually much less than the incremental cost of premiums at higher benefit levels.

Silver – Below 200% of FPL. To qualify for cost-sharing reduction (CSR) benefits, enrollees must have an income level below 250% of FPL and select a silver plan. The CSR benefit for enrollees between 200% and 250% of FPL is mild and they are advantaged by purchasing a richer benefit gold option which should also be lower priced. The platinum-like benefits received by CSR enrollees with incomes below 200% of FPL outweigh the relative price discounts in other metal level plans.

Gold – Between 200% and 400% of FPL. “Buy bronze unless it’s free” is a simple mantra that enrollees ineligible for CSR benefits should remember. While the incremental premium difference between bronze and gold plans sometimes exceeds the cost-sharing difference, the selection of a free bronze plan is effectively not utilizing all subsidy dollars available. In this case, the buy-up from bronze to gold is not the full premium cost difference and paying the incremental premium is a better value than assuming more cost-sharing risk.

Platinum – Nobody. There is little advantage to purchasing a platinum plan today based on a price and benefit value comparison. It’s conceivable that it may be the best value in the rare instance where gold plans are free for all subsidized enrollees. Overall, the underuse of platinum level plans on the marketplace would allow public option enrollment to not disrupt current market dynamics.

Presidential Plans

President Trump’s campaign website speaks more of achievements than future plans. It doesn’t propose any legislation. The president’s work has been primarily regulatory in nature, and much of it is still being implemented by states and the marketplace. The president does not discuss the potential of a public option and has promoted consumer and state-based flexibility through regulation.

Joe Biden, the likely Democratic nominee, is prescriptive about two items specific to ACA dynamics. He proposes eliminating the income cap[3] on premium subsidy eligibility and calculating premium subsidies “based on the cost of a more generous gold plan, rather than a silver plan”. The market dynamics have changed since Mr. Biden left public life, and this proposal is actually a less generous subsidy calculation. With defunding of CSR payments, silver plans are priced higher (generating higher subsidies) than gold plans in many states and ultimately will be nationwide.

Mr. Biden also suggests that a “public option will reduce costs for patients by negotiating lower prices from hospitals and other health care providers”. This prescription is consistent with that of Mr. Reich and in line with proposals underway in Colorado and Washington.

Will the Platinum Public Option Work?

To start, offering a platinum-only public option can cause little harm. There is not an active market for platinum plans, so there is little to mess up. It doesn’t interfere with the subsidy calculations and harm low-income enrollees that a silver or gold level public option might do.

The primary challenge of a “public option” will be getting medical providers to agree to required lower reimbursement levels. Why would providers agree to a lower reimbursement rate? There must be something in return. There are two potential benefits from a provider’s perspective; one is inclusion in a narrow network, which will help with steerage and patient volume. Depending on the providers included, a narrow network public option might be less attractive to some consumers.

The second potential benefit for providers is revenue collection. If there is one thing providers dislike more than lower reimbursement, it is having to staff their office to spend significant time billing, calling and collecting payments from individual patients. They would much rather deal with one payer (an insurance company) than rely on patient payments as a significant portion of their revenue stream. Platinum benefits are very rich, and plans are usually structured with copays that can be collected at the time of service; some plans have deductibles that apply to certain services. In 2020, the average platinum deductible is $101 compared to $4,181 for silver plans. Just as traditional Health Maintenance Organizations accepted lower negotiated rates, providers may be more willing to accept lower payment rates if they only apply to rich benefit plan offerings.

Conceptually, a Platinum Public Option would not disrupt sensitive market dynamics and would be more agreeable to the provider community. It would satisfy the various constituencies who seek more direct government involvement in ACA markets, an offsetting benefit in consideration for acceptance of lower reimbursement levels, and preservation of current dynamics that have led to recent ACA market improvements.

Conclusion

ACA markets have strengthened in recent years and will continue to improve if unabated. My concern is not that markets will not improve without federal legislative changes, but that such market improvement will be slow to develop and policymakers will grow impatient. As I warned last year while encouraging swifter action from states and insurers, a delayed market response could result in “prompting lawmakers unfamiliar with the market mechanics to prematurely stop the gold rush.”

The primary catalyst for market improvement and low-income enrollees paying less has been the enhancement of premium subsidies calibrated to silver plans serving CSR enrollees with platinum-like benefits. The movement to market equilibrium has been slower than some stakeholders expected, and divergent responses at the state level are significant. However, it is important to recognize that real market improvement has occurred (and still developing in some states) and it would be thwarted by recalibrating premium subsidies to gold level coverage or blindly introducing a public option into ACA markets.

A Platinum Public Option would not interfere with the subsidy dynamics and would provide a more agreeable platform for medical providers. A Lionfish Public Option would wreak new havoc, create premium problems for consumers, and likely reignite ACA repeal efforts. Would a Platinum Public Option help ACA markets? Yes, to some extent. It would provide some use for the platinum metal tier and satisfy those who value a more public role on the ACA platform. Most importantly, public discussion of the Platinum Public Option will let states, insurers, and ACA consumers know that the “public option” plan on the horizon will not the wrecking ball that they might have expected. The reassurance of market sustainability will promote state initiatives to optimize their markets and maintain a long-term focus on ACA sustainability. If you hear the promotion of a public option and your sincere desire is ACA preservation, ask if it is ‘The Lionfish Public Option’ or ‘The Platinum Public Option’ being proposed, and be prepared to explain the fundamental importance of the question.

Greg Fann has been a thought leader on the financial dynamics of the ACA since 2011. Please contact Greg at greg.fann@axenehp.com to discuss opportunities to improve ACA markets.

Endnotes

[1] Platinum selection represented less than 1% of enrollment in 2019 and 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/4120-health-insurance-exchanges-2020-open-enrollment-report-final.pdf

[2] There are some nuanced exceptions; these recommendations are intended for consumers and their agents who are not interested in performing time-consuming detailed calculations when selecting plans.

[3] This would lead to almost all enrollees paying a percentage of their income for health insurance. There would little interest among consumers and their advocates in keeping premium costs down because premiums that consumers paid would be based on income rather than health care.

About the Author

Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.