And the dreams that they’d been living in the California sand

Died right there beside him in Cheyenne

– Garth Brooks, The Beaches of Cheyenne

Abstract: California’s Affordable Care Act (ACA) state exchange is the most active, the most recognized and “considered one of the country’s most successful”. But does California have the strongest ACA market? My colleague analyzed 2020 nationwide subsidized and unsubsidized premiums at a high level, and California’s relative score was average. What measures determine strength and market success? What has California done that other states have not? Do these actions have tangible results? What else can be done to provide a competitive edge? Could California’s dream of establishing the country’s preeminent ACA paradise have already died in flyover country? In recognition of further potential opportunities for states to optimize their ACA markets and poor stakeholder understanding of market mechanics, these are questions worthy of closer examination.

I spent most of Memorial Day weekend in my backyard, about an hour from the San Diego coastline. More time was dedicated to writing rather than grilling, and I wrapped up a four-part series titled “The Affordable Care Act (ACA) Makeover”. It records the significant changes in the premium subsidy (aka tax credit) structure beginning in 2018 that is being phased-in at various speeds in the 51 (each state and Washington, DC) “single risk pools”. The impetus for the makeover was President Trump’s executive action on October 12, 2017, that bolstered silver plan premiums and premium subsidies, vastly improving federal assistance for millions of Americans. Amidst countless reporting of purported implications of proposed legislation with little chance of traction in a divided Congress, the ACA Makeover explains what will happen in the more likely scenario of the ACA being legislatively undisturbed.

Contemporary Chronicles

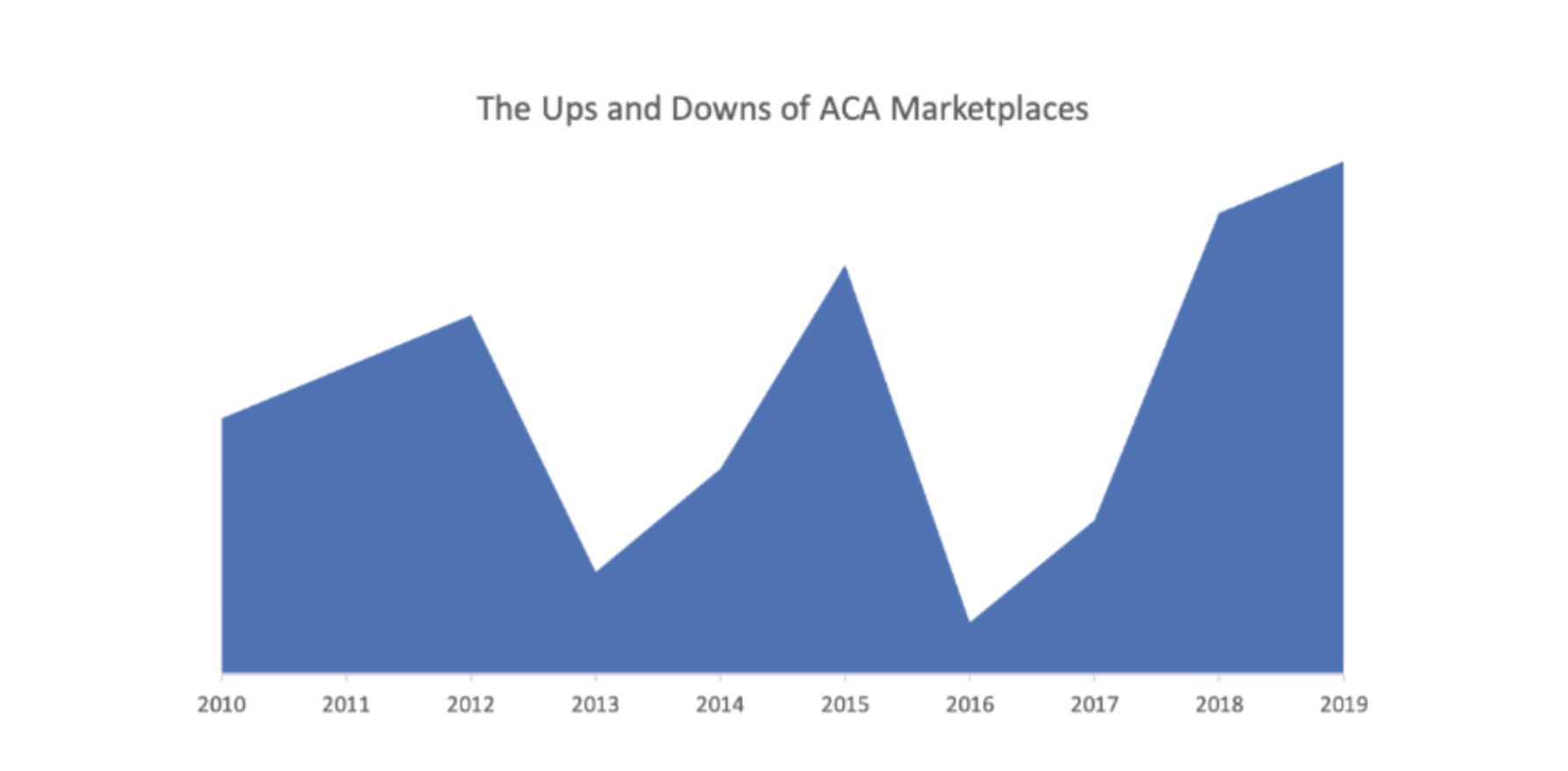

The recent factual history is undeniable. ACA markets were crumbling in 2016 and legislative acknowledgment of a failed experiment appeared imminent. However, the repeal appetite of the incoming Trump administration, particularly the presumed interest in scaling back new federal assistance for low-income individuals to procure health insurance, was collectively overestimated.

The president labeled the repeal bill “mean”, said the Senate needed to be “more kind, more generous”, and added that it could use more “heart” in the form of additional money for consumer tax credits.

President Trump showed his cards in June 2017 with his “private” reaction to the American Health Care Act (AHCA), the only successful ACA repeal legislation, which he had publicly called a “very, very incredibly well-crafted” structural correction to the ACA. The president labeled the repeal bill “mean”, said the Senate needed to be “more kind, more generous”, and added that it could use more “heart” in the form of additional money for consumer tax credits. Despite raising eyebrows for pumping the brakes on repeal momentum, the president’s sentiments toward larger federal support for consumers in individual markets were only momentarily recognized and quickly forgotten by the experts.

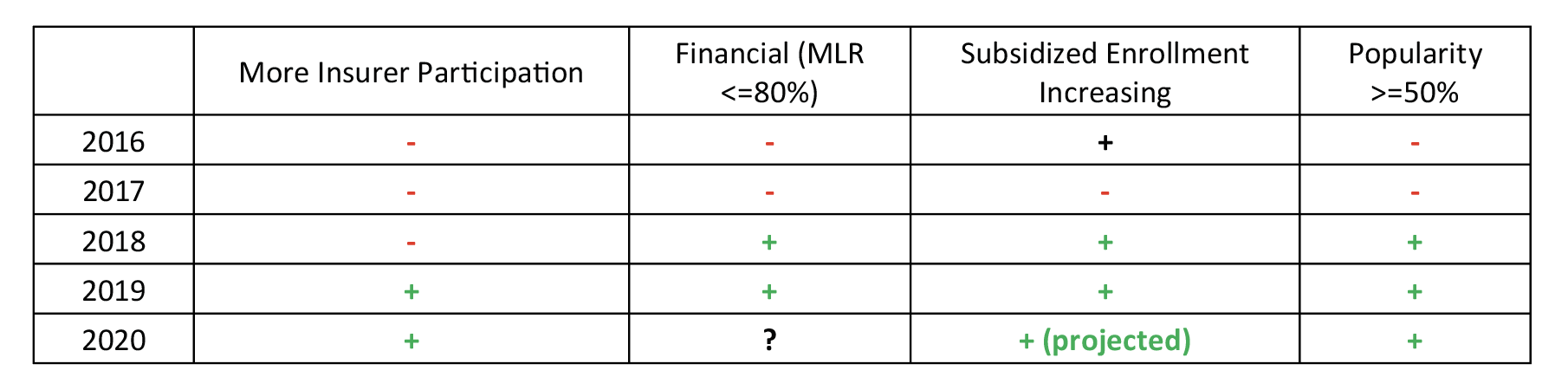

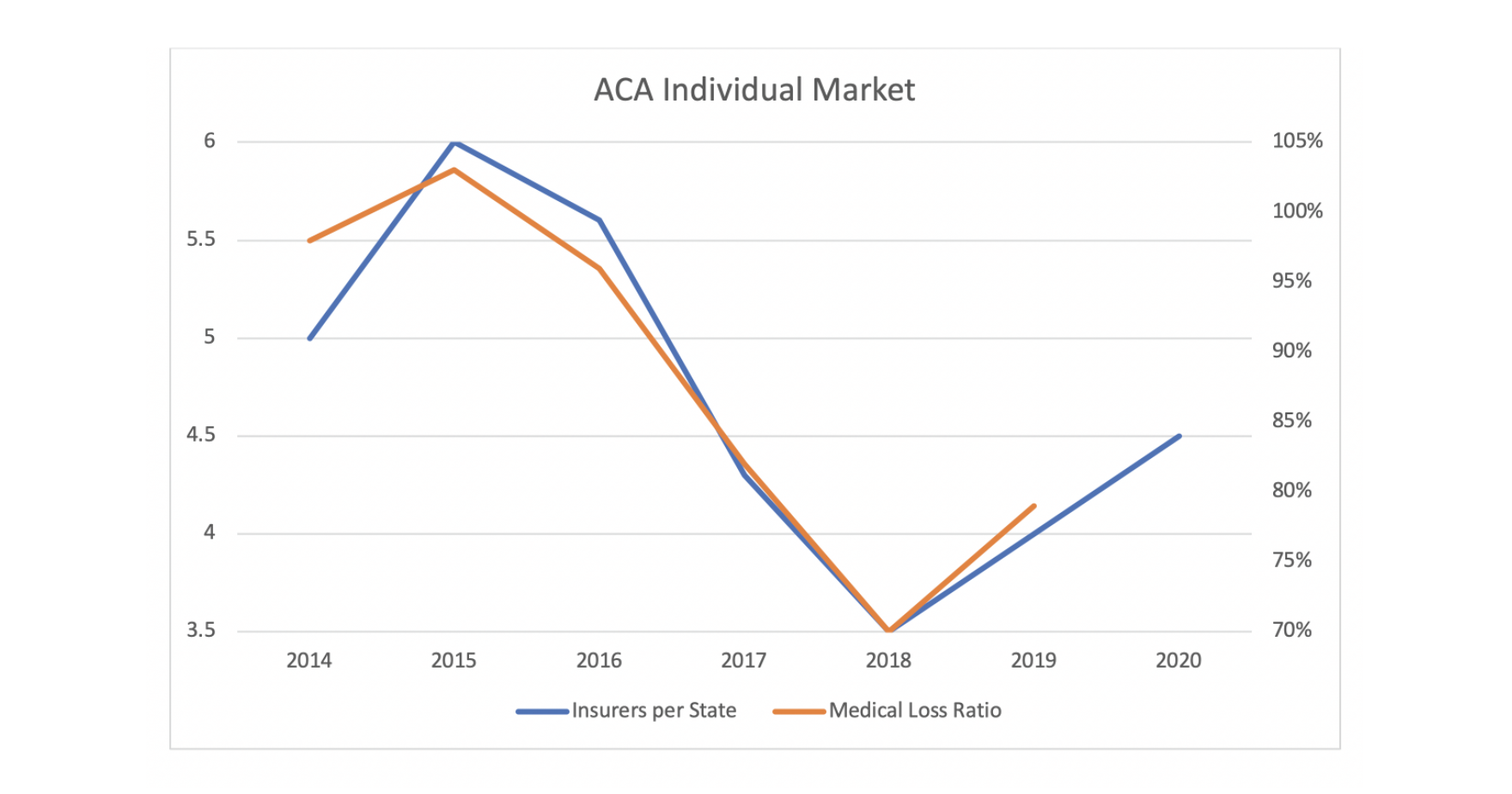

With the premium subsidy boost ignited three months later by the defunding of Cost-Sharing Reduction (CSR) payments, ACA markets noticeably turned in 2018. Net premiums plummeted, enrollment significantly exceeded expectations, and insurer profitability skyrocketed to record levels. ACA premiums decreased for the first time in 2019 and surprisingly did so again in 2020. The beneficial market changes attracted insurer interest, and the number of state-levels insurers increased in 2019 and 2020 after a 28% reduction in 2017 and a 21% reduction in 2018. In 2019, the law’s least popular provision (individual mandate penalty) was stricken, subsidized enrollment continued to grow despite mandate proponents’ anxieties, and recent polling responses indicate that the law is more popular than ever, with more people reporting they have been helped and fewer acknowledging harm from the law since 2016.

The chronicling of the ACA market rebound contrasts the common narrative in the public sphere which deliberately masks the market improvements under the supposed guise of President Trump dismantling the ACA, gutting federal funding, and rendering ACA markets less attractive. While the actual results are objective and plain for all to see, the true story is kept quiet and the rationale for silence is discernable.

I will say it out loud: the facts do not align with anyone’s politics, and it is therefore a story that few people want to tell. As I revealed in 2018, President Trump’s policy impact is “largely veiled in public discourse as it is disassociated with either political party’s goals or talking points”. ACA policy implications do not conform to natural partisan alignment or advance anyone’s political agenda, but understanding the apolitical market mechanics is essential to advancing future federal and state policy; this is a story that must be told. I have been a leader in researching and expressing the divide between ACA reality and politically-based messaging since 2017, but I was startled and painfully reminded over the recent holiday weekend how deep the chasm really was.

Leisure Learning

Back to Memorial Day weekend…the weather is nice, and I am outside writing and watching rabbits eat my back yard. I am enjoying the comfortable environment and the fact that I am not particularly rushed. While searching for a footnote source, I stumble upon a couple of radio interviews from 2017. The topics pique my interest, I have sufficient battery juice on my laptop, and I decide I have time to listen. The moderator is Larry Mantle, a Los Angeles based public radio host with a recurring show about local news, politics, science, and entertainment. I am not familiar with him, but I immediately liked his voice and his style. I am not sure what it is about me and the radio guys, but we all share a birthday: Rush Limbaugh, Larry Mantle, Howard Stern and me; I am 50, they were born in the 50s.

Mr. Mantle is affable, he is easy to listen to, and his follow up questions are on point and give his guests opportunities to clarify and correct answers. The subject matter is my direct area of expertise and he asks the questions I would ask based on the responses provided. He does not combatively challenge the various wrong answers he receives, and it’s not clear if the technical details are beyond his scope, his time to probe is limited, or if he simply knows how the game is played and moves on. Either way, he brings out answers that render it easy to sharply discredit his guests with a retrospective review.

The topic for both discussions is the implications of President Trump’s above-mentioned executive action. The guests agree on basic facts, and then expectedly disagree with commentary arising from differing political perspectives. Some may find the political debate of interest; what is fascinating to me (and not in a good way) is not the debate of dissenting opinions, but that the basic facts they agree upon are grounded in political suppositions rather than mathematical reality. Throughout the discussions, Mr. Mantle offers multiple opportunities to consider other viewpoints and soften their strong positions, and they never oblige.

Radio Review

Guests for the first interview are California Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones, KPCC health reporter Michelle Faust, and Sally Pipes, president and CEO of the Pacific Research Institute. The interview with Mr. Jones was prerecorded; his consistent message is that California is doing everything possible to counteract President Trump’s actions, which he assuredly believes are harmful to ACA markets. His criticisms extend beyond policy implications and ascribe nefarious intentions; he says “the President continues to wield a club trying to wreck the ACA” and “since day one, the president has been working to undermine the ACA” and even threatens to “sue him”. He attributes insurer market exits across the country singularly to Trump-induced uncertainty. Mr. Jones is universally critical of the Trump administration’s actions, specifically noting the administration “issued regulations collapsing the open enrollment period and is allowing lesser valued plans to be sold outside the exchanges”.

Mr. Mantle repeatedly suggests that some problems in ACA markets preceded President Trump and that there were pre-existing market concerns “about long-term viability without tweaks”. He offers opportunities for clarification, but Mr. Jones’ blame for insurers leaving markets and only dissatisfaction lies with the president. Ironically, and probably overlooked by all, President Trump’s action was the unforeseen “tweak” that ACA markets needed for long-term viability.

California’s state exchange determines its own open enrollment period, so the “collapsing” complaint is a bit opportunistic and not relevant to California’s market. Upon the request of the insurance industry to protect risk pools, President Obama’s administration implemented regulations that reduced the open enrollment period in federal exchange states to 45 days beginning in the plan year 2019. President Trump implemented the change a year earlier, much to expressed chagrin of his critics. Subsidized enrollment increased in 2018 after declining in 2017, so the criticism was not supported by evidence. Genuine opposition to a reduced open enrollment period seems illogical, whether based on the expected or actual results, and appeared to be more personal than policy-driven.

Perhaps Mr. Jones’ most illuminating comment is his recitation of “allowing lesser valued plans to be sold outside the exchanges”; the California history uniquely illustrates how political calculus alone can drive policy decisions. States have traditionally been free to regulate local health insurance markets without significant federal oversight. Before 2017, California regulated short term health plans, limiting their term to 185 days. This policy reflected California’s values and generated little controversy.

Effective 2017, President Obama issued an executive order limiting short term plan duration to 90 days, overriding the California rule. President Trump later relaxed Obama’s decision, effectively putting the California regulations back in place. In response to the proposed rule which reinstituted California law, Commissioner Jones offered comments in a letter to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) administrator, calling President Trump’s action “another attack on the integrity of the nation’s health insurance markets”.

California prohibited the sale or renewal of short-term health plans in September 2018. Rather than accept a reversion to California policy, the state retaliated against President Trump’s action and removed these insurance products from its market. The politics surrounding this tiny market segment have become oversized relative to the policy impact. Left alone, California regulated short term plans as it wished. When a minor insurance product became politicized, California took a stand and canceled an insurance market. This is emblematic of responses to ACA changes, which are generally politically reflexive without regard to apolitical consideration of underlying policy implications.

Ms. Pipes’ reaction to Mr. Jones’ comments is primarily a reminder that ACA problems existed prior to President Trump, and she opines that his election was largely due to ACA dissatisfaction. She correctly notes that insurer market exits began before President Trump assumed office, that early financial results were poor, and that initial market enrollment was older than its architects projected. The Trump-induced insurer exit theory is suspect, as insurers returned to markets in 2019 and 2020 after observing record financial results in 2018. Mr. Jones is correct that some insurers did message federal uncertainty approaching 2018, but insurers leaving markets was a continuation from two of the ACA’s worst years, not a directional change catalyzed by President Trump’s executive actions. Mr. Jones’ market exit rationale should be understood in light of “internal/external rationale” considerations that I described in an article published just a few days before the interview.

There are external pressures for insurers to support the ACA and “participation in this high-profile market is more involved than an isolated business decision based on a financial forecast.”

Insurers have experienced significant losses, and market exits and the potential of “bare counties” have permeated the news since 2016, although many insurers have remained in the market despite a poor financial outlook. Recently, the CSR uncertainty has been used as an external rationale to exit markets as it is easily explained and understood, while the pattern of market exits (which existed before the CSR discussion) are likely the result of other challenging dynamics. Insurers have until September 27th to finalize 2018 decisions regarding ACA market participation; it would be foolish to believe that an insurer with strong performance has decided to exit the market prior to this date solely due to CSR uncertainty. Likewise, the same insurer would likely benefit from CSR defunding assuming its rates properly reflect the new dynamics.

The second interview includes Ms. Pipes and Gerald Kominski, professor of health policy and management at UCLA and director of the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research.

Like Mr. Jones, Mr. Kominski alleges bad intentions are behind President Trump’s executive action, noting “the CSRs are going to harm people below 250% of FPL…they are going to be harmed. This is a deliberate and conscious attempt on the part of the president to harm some of the most vulnerable members of our society. I think it’s unconscionable“, and “he (President Trump) has decided to force a crisis…what he is doing is holding low-income people hostage.” Mr. Kominksi suggests that CSR ”payments are essential to make health insurance affordable to the people at the lowest end of the income scale”. He theorizes that net premiums are going to increase and asserts more people will consequently be uninsured. When asked to respond, Ms. Pipes alternatively indicates that current subsidized consumers will not become uninsured but will gravitate to non-ACA solutions (Association Health Plans, Health Reimbursement Accounts, etc.) that have been favored by Republicans.

This exchange is reflective of a dynamic that is somewhat unique to ACA discussions; “instead of having two political narratives competing over truth, we have two political narratives that are in agreement with each other but disassociated from the truth.” Mr. Kominksi is correct that the off-market plans Ms. Pipes is promoting will only attract people with incomes above 400% of FPL, not the consumers directly impacted by federal subsidy changes. He refers to “affordability” as driving plan selection decisions, but the decision point is better described as “consumer value”. ACA premiums are extremely expensive and relatively unattractive at full price. However, most ACA enrollees with incomes under 400% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) receive subsidies and can find a better value in ACA markets.

Mr. Kominski is wrong on the implications to subsidized enrollees and Ms. Pipes agrees with him. Mr. Kominski believes that more low-income individuals will be uninsured due to Trump’s action and Ms. Pipes believes the ACA harm will lead them to non-ACA products. Of course, the truth is that more low-income people will enroll in ACA markets because President Trump’s action enhanced consumers’ subsidies rather than reducing them.

Neither Mr. Kominski nor Ms. Pipes speaks directly to the real dynamics, and it is unclear how important precision of policy implications is to either guest. Ms. Pipes is there to promote non-ACA products and regard the ACA as a failed legislative experiment. Mr. Komiski is there to champion the ACA and deflect its faults to a new president who was uninvolved in its formation. Implicit biases likely play a role in the failure to objectively understand policy matters. The questions are about the implications of CSR action; they both answer incorrectly and provide answers aligned with political ideals.

Obscurely Obvious

The dichotomy of public information related to the president’s CSR action is novel. As the implications are paradoxical, competing narratives from the traditional political media and wonky health policy information distributors tell different stories.

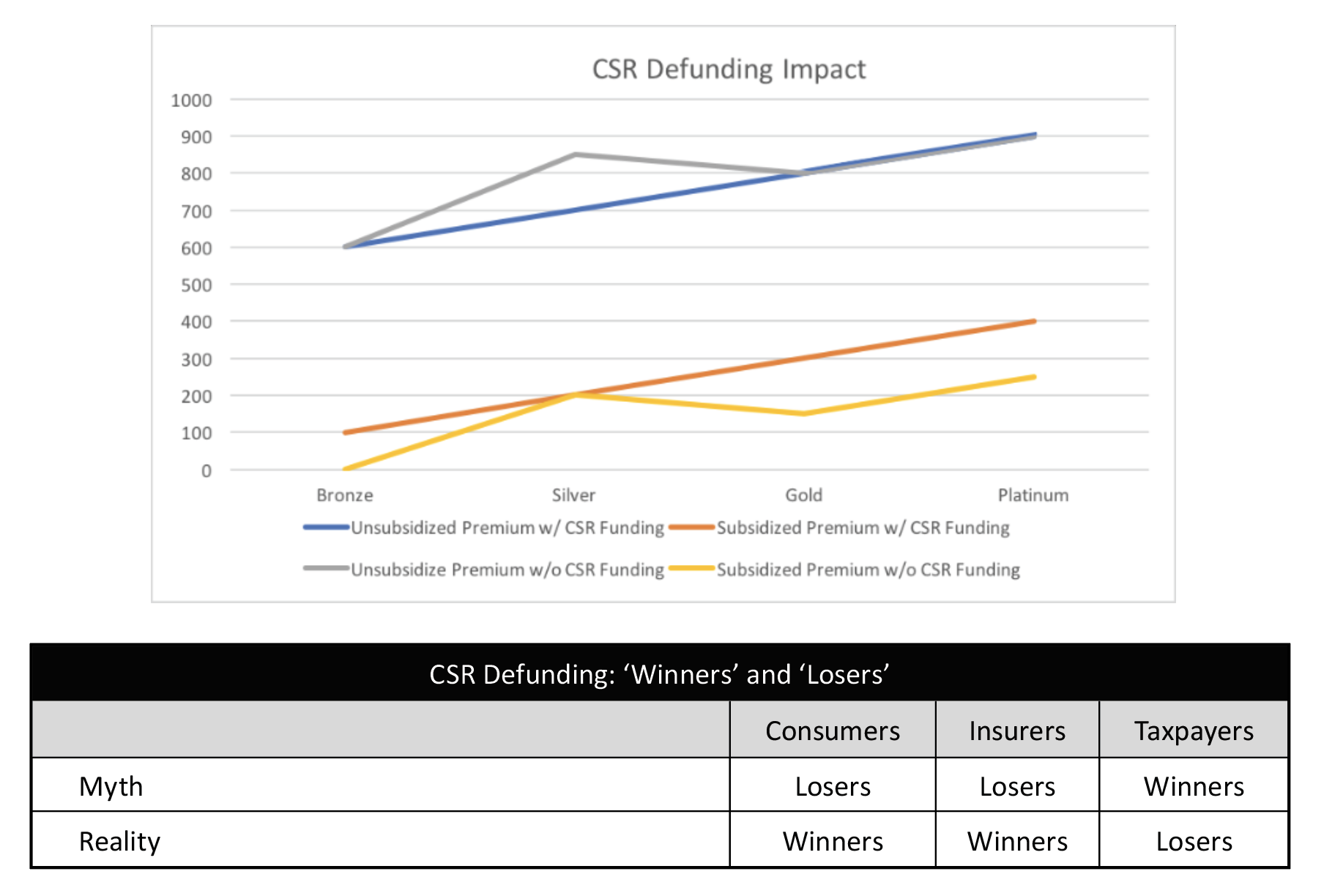

While obscure in the mainstream sphere, Linda Blumberg and Matthew Buettgens of the Urban Institute were the pioneers of explaining CSR defunding dynamics. In January 2016, they concluded that “premium increase(s) would, on average, make silver plan premiums higher than those of gold plans. The higher premiums would in turn lead to higher federal payments for Marketplace tax credits because such payments are tied to the second-lowest-cost silver plan premium. All tax credit–eligible Marketplace enrollees with incomes up to 400 percent of FPL would receive larger tax credits, not just those eligible for CSRs.”

On August 1, 2017, I demonstrated the net premium reduction for subsidized consumers (orange to yellow line) and wrote, “An understanding of these mechanics challenges the conventional wisdom on CSR Funding. The table illustrates the Myth versus Reality in terms of the financial ‘Winners’ and ‘Losers’ of an appropriations decision to not fund CSRs.”

Mr. Mantle’s interview with Mr. Jones, Ms. Faust, and Ms. Pipes occurred on August 3, 2017.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) issued its report “The Effects of Terminating Payments for Cost-Sharing Reductions” on August 15, 2017. It largely aligned with my conclusions but added that stakeholder understanding would take time. I later paraphrased the CBO’s comments, “Listen. We understand how this works. In this report, we are going to tell you how this works. However, we do not think you will understand how this works by simply reading this report. After you observe how this works and recognize the benefits, you will take steps to re-enter markets.”

On September 29, 2017, Wendy Barrett, a licensed Covered California broker said “There is good news if you qualify for Advanced Premium Tax Credit (APTC). The APTC that low to middle-income Californians receive is based on the second-cheapest Silver plan in their area, so if the CSR surcharge is put into place, then consumers who receive tax credits should have more help in paying their premiums with an increased APTC.”

On October 11, 2017, Covered California said “Most Covered California consumers who receive financial help in the form of an Advanced Premium Tax Credit, or subsidy, will not see a change in what they pay for their insurance in 2018 because of the surcharge, and many will actually end up paying less because their subsidy amount will increase more than the surcharge.” The Los Angeles Times reported, “Taxpayers, not consumers, will bear the brunt of the extra rate hike because federal premium assistance for policyholders, which is pegged to the cost of coverage, will also increase.”

On October 13, 2017, the Washington Post reported “President Trump is throwing a bomb into the insurance marketplaces created under the Affordable Care Act, choosing to end critical payments to health insurers that help millions of lower- income Americans afford coverage.” Mr. Mantle’s interview with Mr. Kominski and Ms. Pipes occurred on the same day.

On October 27, 2017, I was quoted in the LA Times on the upcoming open enrollment period. It should have been a story about consumers benefitting from regulatory changes and new considerations for plan selection; instead, that was a small part of a story about confusion.

In May 2018, the CBO said “between 2 million and 3 million more people are estimated to purchase subsidized plans in the marketplaces than would have if the federal government had directly reimbursed insurers for the costs of CSRs.”

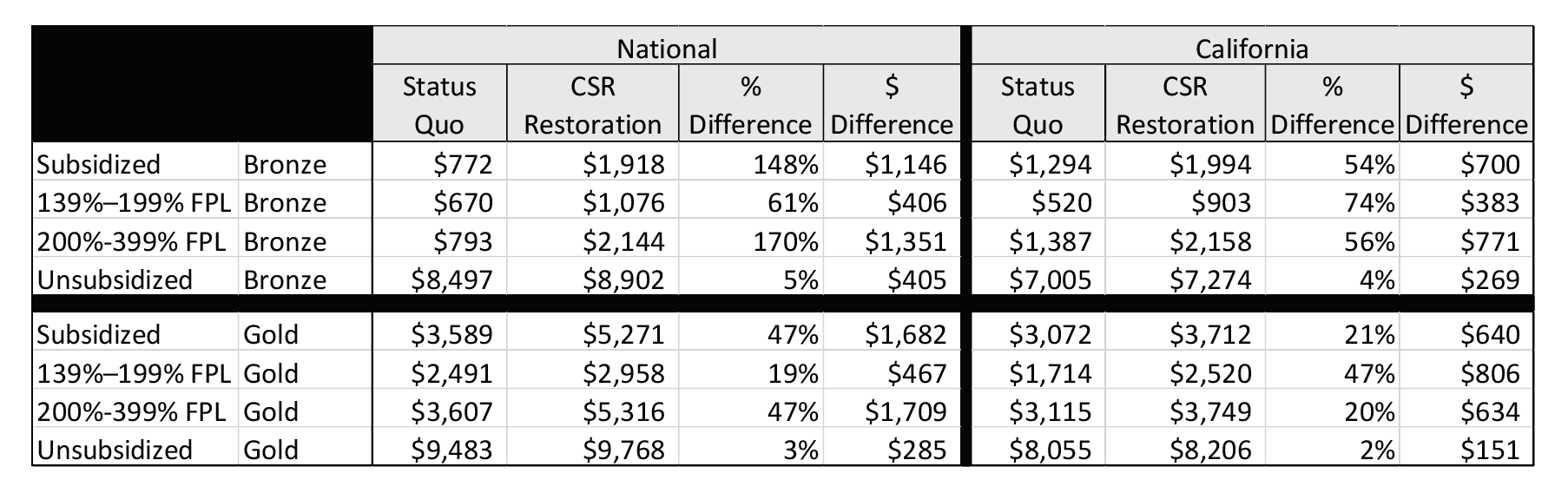

In 2019, a RAND study concluded “restoration of CSR payments would lead to lower federal spending on APTCs, it would also lead to higher premium costs for many consumers and lower insurance enrollment” in California and nationwide. The reversal of President Trump’s executive action would have a significant impact on subsidized enrollees and reverse the gains that state markets have achieved.

In September 2019, Stan Dorn, a liberal advocate at Families USA, wrote in a Health Affairs blog that the Trump policy might be better than a financially equivalent offering that Democrats may propose, stating “At first blush, the proper and rational course appears obvious: Restore CSR payments, end silver loading, and use the federal savings in a more carefully considered, thoughtful way…But until further research demonstrates the effects of such alternative policies and identifies win-win solutions with outcomes that far surpass the results described here, policymakers should think long and hard before discarding the silver-loaded fruits of actuarial wisdom.”

While reporting of the CSR defunding action as beneficial was not universal, it was well understood in policy circles. Unfortunately, it did not reach Mr. Mantle’s radio guests in 2017 and has not resonated with the mainstream media and general consumers today. Accordingly, consumer education is lacking, and enrollees continue to make poor plan choices which slow the ACA makeover and keeps premium subsidies compressed. The 2020 elections fall within the 2021 open enrollment period; it is not beyond the realm of possibility that the discussion will shift from a politically-based understanding of the ACA to a mathematical understanding of the ACA in mid-November. Politically-based messaging, including the Congressional charade at the Supreme Court, will likely continue through November 3rd.

Everyday Experts

I was speaking with a US Senator in February and I told him that his party was not getting anywhere with health policy because every hearing is the same witness saying the same things. It surprised him that someone who lives 2700 miles from Washington, DC would notice something so wonkish.

Members of Congress are bright people, many of whom had successful careers in various private sector fields prior to public service. Some are attorneys, some are physicians, none are experts on health insurance mechanics. They have “experts” to guide them, and the experts are political people with policy expertise.

The guests on Mr. Mantle’s show are representative of who we might see at Congressional hearings. They offer few surprises, and their remarks are often directly aligned with the policy goals of either party. The parties each have a number of allotted witnesses to select for hearings, and they handpick people who support their political goals and maximize their comfort level; new information is rare, consequently, we do not learn much.

People like me are sometimes but rarely invited to speak at Congressional hearings. It is not because either side believes objective mathematical commentary is not valuable. They would both prefer more objective witnesses at hearings; they just do not want to use one of their picks to get there.

How should we decide who is an “expert”? It is not a rhetorical question, but at least in the field that I understand, the “experts” are not really experts. They are politically-guided people who specialize in specific policy areas. When the policy is complicated and not politically aligned, they often miss the substance. Actuaries are objective, dispassionate professionals with unique insights on insurance markets; “the Society of Actuaries provides trusted and objective actuarial research, analysis and insight on important societal issues.” Actuarial testimony of the current ACA dynamics would facilitate better market understanding and inform stakeholders how to constructively respond in the current environment.

We are on the wrong road to understanding the ACA; we are on a road paved with politically-based suppositions.

We are on the wrong road to understanding the ACA; we are on a road paved with politically-based suppositions. As ACA markets grow stronger each year, the conventional wisdom is that the opposite is true. We do not need a federal correction now based on the events of the last three years. The federal correction has occurred; we are simply waiting on downstream stakeholders to properly implement the correction; that will take some time, but we would acknowledge its occurrence if we were on the right road.

Instead, we are lost sheep on the wrong road. ACA markets have been in heading in the right direction since 2018 and most of us still do not realize this. The danger that I expressed last year was not that ACA markets would not improve if left alone, but that we would miss the progression of market improvement and would grow impatient, “prompting lawmakers unfamiliar with the market mechanics to prematurely stop the gold rush.”

I have heard few people in the political sphere express a strong understanding of ACA markets. An exception is liberal activist Jon Walker. He is refreshingly honest about policy implications and pretty much everything else about the ACA. He says that “Democrats have failed to build on the Affordable Care Act — not from a lack of good intentions, but because of the fatal complexity of the law itself. That same complexity has kept the media from reporting on Democratic failures to build on its own law, which has created the space for Biden to be able to pretend that he’ll be able to do so. But ultimately, it’s as if the party still hasn’t figured out how to get the lights to work in the house, but are confident the answer is an expensive addition… Collectively, these regulatory decisions made in blue states have cost low-income individuals billions, and needlessly caused tens of thousands to go uninsured.”

Essentially, Democrats’ actions since 2017 have been to reflexively retaliate against President Trump. If you are politically-inclined but uninterested in understanding how the ACA works, I suppose presuming the president’s action will harm markets is the only place to start. It has not worked for left-leaning states. I have looked at multivariate scenarios of state decisions and state markets; expanding Medicaid does reduce uninsured rates, but there is little else to suggest that Blue states have had more ACA success than Red states, despite claiming to be ACA champions and expending more time, effort and money toward that cause.

On October 23, 2019, Congress held a hearing titled “Sabotage: The Trump Administration’s Attack on Health Care”. Opening comments included “Today’s hearing continues this Committee’s ongoing work to bring oversight and accountability to the Trump Administration’s relentless attack on people’s health care. Whether it be attacks on the Affordable Care Act, Medicare or Medicaid, since day one this administration has engaged in a concentrated effort to undermine, weaken, and outright eliminate health insurance coverage for tens of millions of Americans.” It was absent in substance and neglectful to recognize the tremendous market improvement since 2016. Market success varies by state, and fair warning, the next section dives deeper into some of the math. It is more exciting than the tiring ‘sabotage’ narrative. Trust me.

Metalball Math

State responses to the ACA makeover have varied, and each is on its own path toward “market equilibrium”. I initially spoke of a market equilibrium last year, which is accelerated by insurers developing pricing relativities in accordance with ACA guidance, states focusing rate review process on meaningful measures, and consumers selecting appropriate plan options. State variations have surprised me; with strict anti-discrimination rules, ACA premium rates should demonstrate more conformity. States that have achieved better compliance have better results.

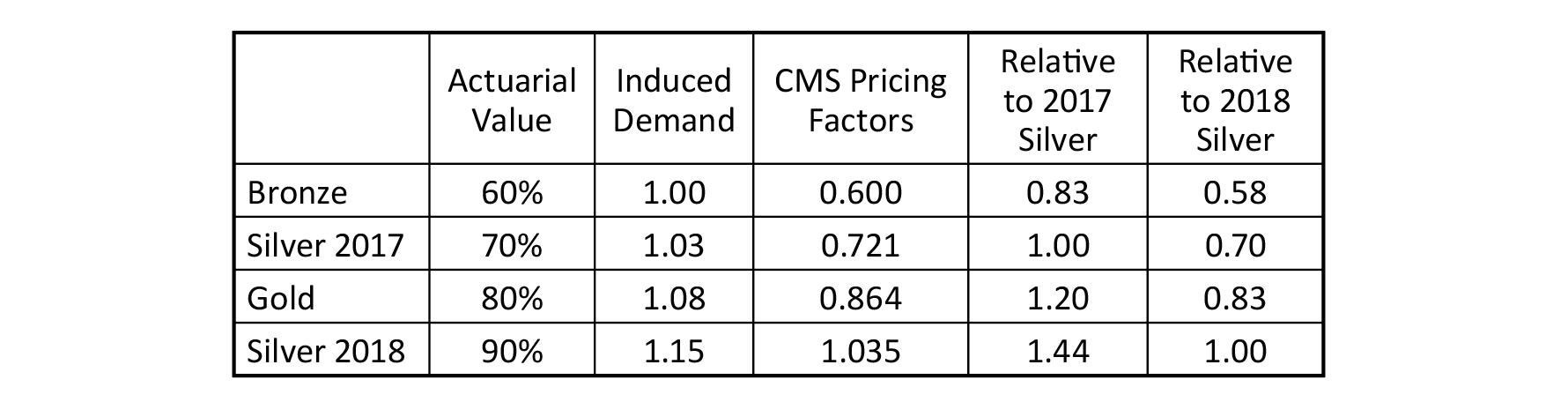

Before looking at some example illustrations, it helps to understand the basic mathematical structure. ACA benefit plans are divided into four metal levels. The benefits of each metal level provide a different “Actuarial Value”, which is the proportion of health care costs paid by the insurer. This requirement is not exact as a few percentage points of grace are allowed; also, benefit compliance is based on an “AV Calculator” developed by CMS and pricing factors are developed using other actuarial models. Nevertheless, pricing expectations should roughly align with Actuarial Value calculations.

For our purposes, we ignore platinum level coverage (90% AV) as its enrollment distribution is less than 1%. In addition to Actuarial Value, insurers develop Induced Demand factors to reflect benefit-induced utilization. Pricing Factors are the product of Actuarial Value and Induced Demand factors. Induced Demand factors simply reflect additional costs due to behavioral changes after benefit selection; naturally, richer benefits induce more utilization than leaner benefits. Directionally, there is a natural alignment between Actuarial Value and Induced Demand factors. Unfortunately, this has not been universally true in ACA markets and compliance enforcement has been weak. As notedlast year, “insurers have introduced experience rating by health status into the Induced Demand factors. The results of these actions reduce the relative Silver premiums, are detrimental to the market, and unnecessarily increase premium costs for consumers.”

Pass through dollars were provided by the federal government to offset the Actuarial Value difference between 70% and the enhanced Actuarial Values. This allowed insurers to be whole by pricing at the base level.

The table below displays the Actuarial Value and Induced Demand factors for each metal level. Again, these are base factors provided by CMS; they are not prescriptive but reflect reasonable benchmarks that should uniformly align with insurer pricing practices. ‘Silver 2018’ reflects silver level benefits after President Trump’s CSR action; the CMS factors are reflective of market equilibrium and reflect long-term market expectations, with gradual alignment progressing each year. The silver Actuarial Value of 70% reflects base silver benefits. Before 2018, insurer prices reflected this level. Many silver enrollees were eligible for CSR benefits and had higher Actuarial Values (73%, 87%, and 94% depending on income). Pass through dollars were provided by the federal government to offset the Actuarial Value difference between 70% and the enhanced Actuarial Values. This allowed insurers to be whole by pricing at the base level.

When these payments were removed, insurers raised silver premiums to account for the loss of pass-through dollars. Silver plans now have a blended Actuarial Value based on the enrollment distribution of the 70%, 73%, 87% and 94% levels. About 75% of exchange silver enrollees nationwide are in the 87% and 94% levels in 2019. As silver premiums are necessarily overpriced for those in the 70% to 73% tiers, wise consumers have migrated to other premium levels. Hypercompetitive premiums at the silver metal level have artificially kept silver premiums low in some states; this slows the natural migration toward equilibrium. For our general purposes, we assume equilibrium with all silver enrollees in the 87% and 94% tier have a blended Actuarial Value of 90%; the Silver 2018 factors in the table below are effectively equal to platinum level plans. Completion of the ACA makeover and achieving nationwide market equilibrium could take another ten years; in 2018, the CBO predicted gold premiums will be lower “by the end of the coming decade” and “the gold plans will provide more generous benefits for people not eligible for CSRs”. Depending on the methodology, between 10-15 states currently have gold premiums lower than silver.

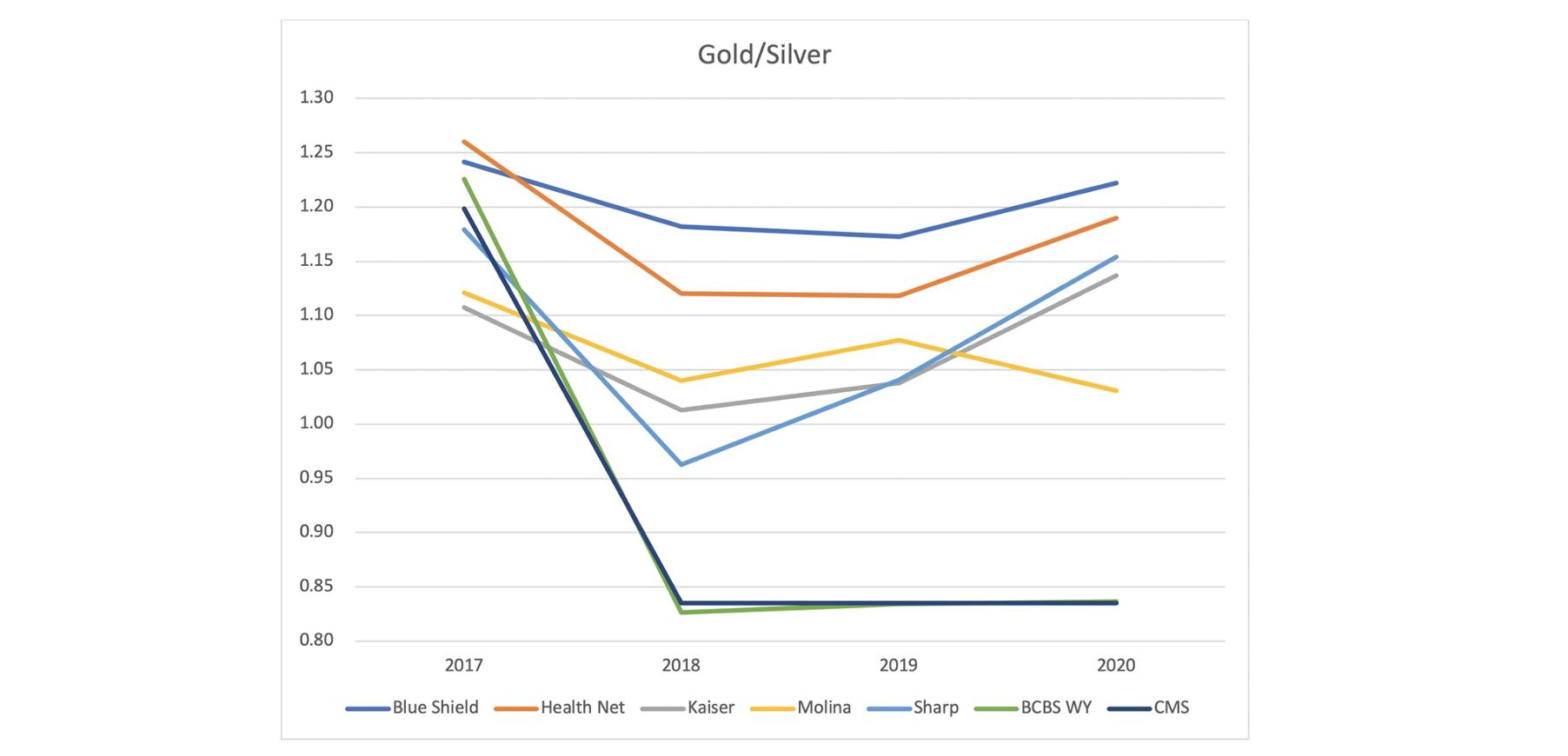

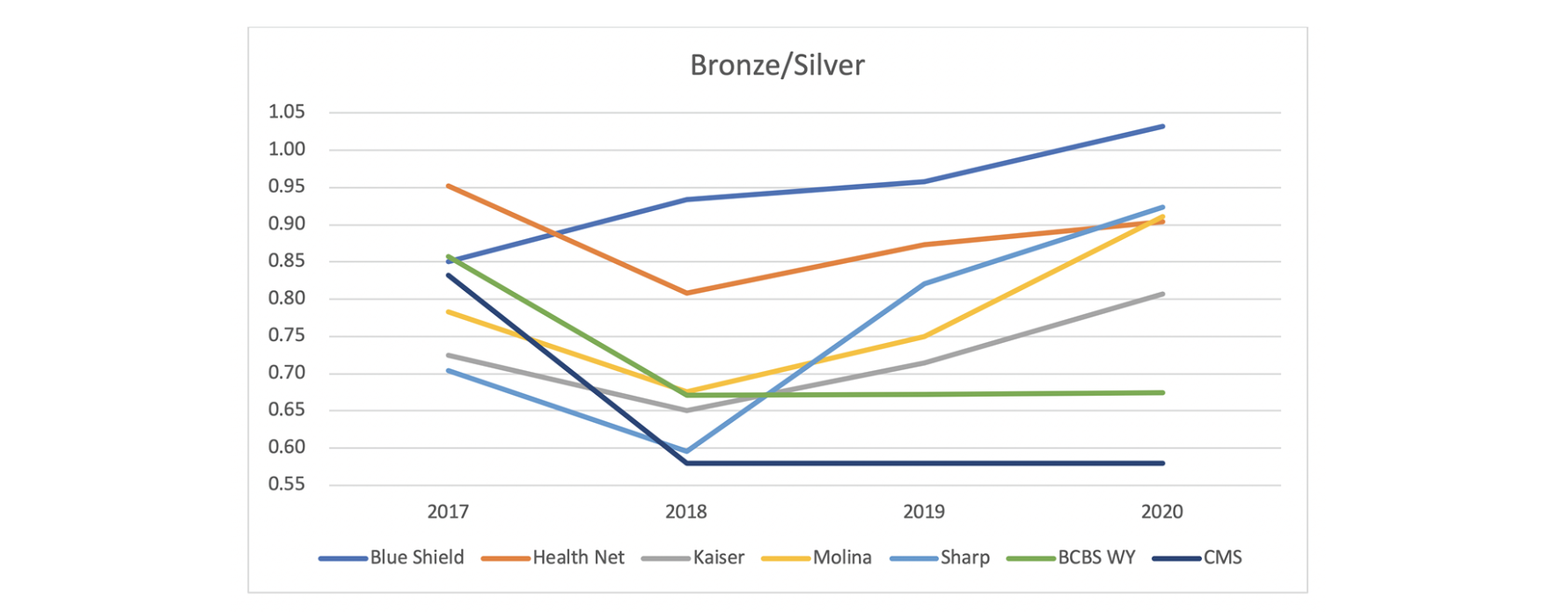

The charts below compare metal level ratios in San Diego, California and Cheyenne, Wyoming. The CMS pricing factors are included in the charts as well to provide a benchmark relativity to market equilibrium. The CMS factors are based on the relationships in the table above with ‘Silver 2017’ applying in 2017 and ‘Silver 2018’ applying in other years. The plan factor relationships are the actual pricing relationship between benefit plans in the Cheyenne and San Diego markets.

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Wyoming (BCBS WY) is the only insurer in Cheyenne. The gold/silver premium is almost identical to the CMS factors. The California plan factors do not line up with CMS factors and vary among insurers as Metalball is active in California. Notably, the Sharp and Kaiser factors are closer to the CMS factors in 2018 but appear to drift away from equilibrium and toward the San Diego market average in 2019 and 2020.

The bronze/silver premium relationships are similar. BCBS WY is the middle of the CA plan factors in 2017. It is reduced in 2018 and remains roughly flat for 2019 and 2020. The California plan factors drift up in 2019 and 2020, and the BCBS WY ratio is lower than the California plans in these years. Unlike the gold plan, the BCBS WY bronze/silver ratio is higher than the CMS factors.

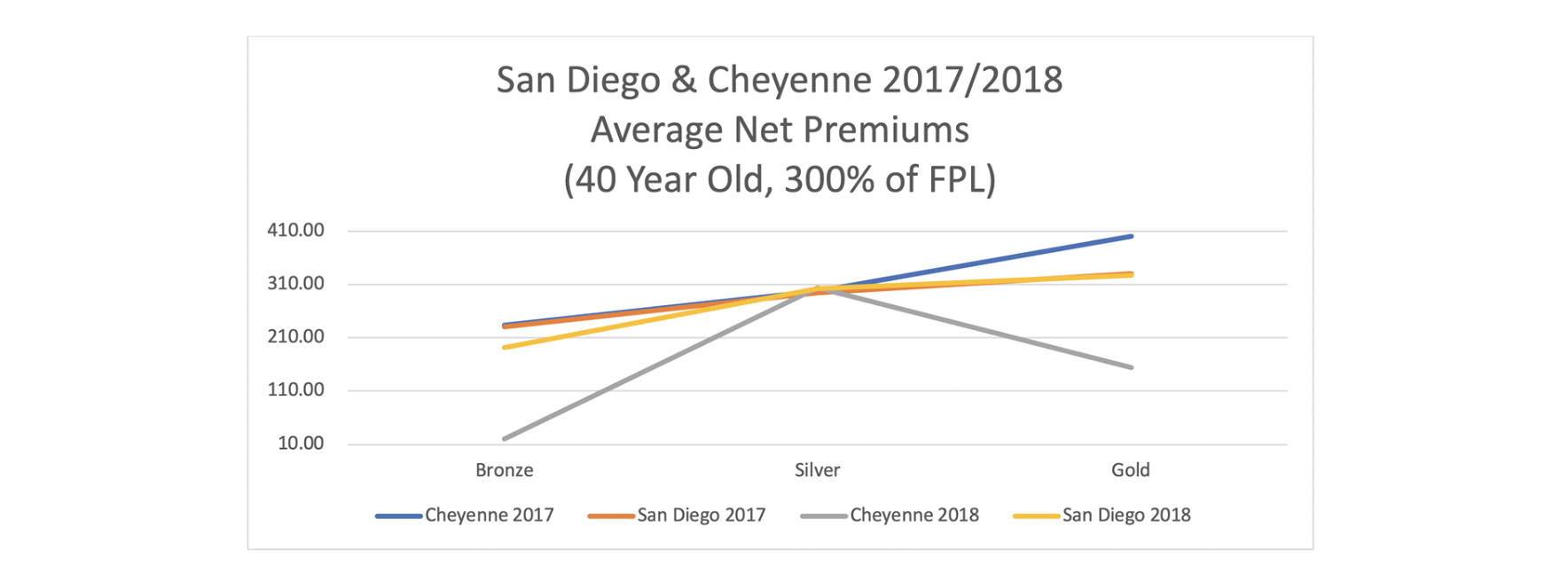

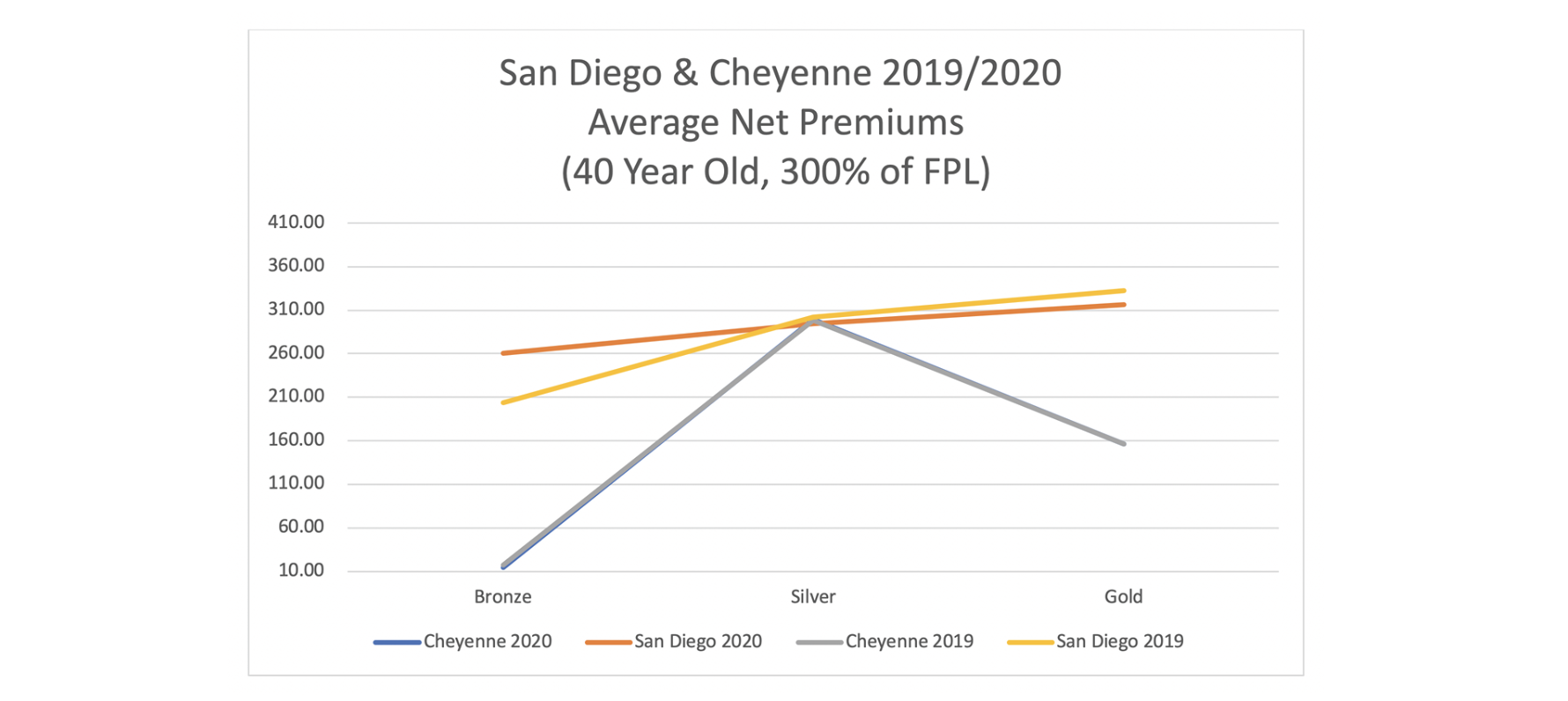

Are these wonky relationships of interest and importance to consumers? It turns out they are the most important relationship. As 75% (and growing each year) of ACA enrollees receive premium subsidies, net premiums (what consumers pay after premiums are reduced by subsidies) that lower-income subsidized enrollees pay are the primary factor determining ACA viability. Actual net premiums vary by age and income level, but the insights and directional results are the same across the demographic spectrum. To illustrate, the charts below display the net premiums for the lowest-cost bronze, silver and gold plans in Cheyenne and San Diego. The first chart shows 2017 and 2018; the second chart shows 2019 and 2020.

The primary change is from 2017 to 2018 when CSR payments were defunded. The premiums are somewhat similar between Cheyenne and San Diego in 2017. Lower-income consumers benefitted in California in 2018, but they benefitted significantly more in Wyoming. Mr. Jones’ dual claim that President Trump’s actions were harming markets and “California is doing everything it can” to improve market dynamics does not align with results. Rather, the results indicate that President Trump’s actions have helped markets, and Wyoming has done more than California to accept such help. The Wyoming results demonstrate the opportunities to reduce premiums for low-income enrollees by achieving market equilibrium.

The results in 2019 and 2020 are fairly stagnant, though bronze premiums did increase in California. Over time, with a concerted effort to eliminate Metalball, California premium relationship should approach the equilibrium, and net premiums should approach the low levels achieved in Wyoming.

President Trump’s executive action enhanced premium subsidies beginning in 2018. Lower-income consumers now have lower net premiums for non-silver metal levels. The subsidy increases are not fully implemented, and net premiums will continue to be reduced at different speeds in different states. Wyoming appears to be fully phased in, and premium relationships have been consistent since 2018. California premiums adjusted initially; California has made little additional progress since 2018. In 2020, California added subsidy enhancements using state funds. This resulted in new subsidies for enrollees between 400% and 600% of FPL and added additional subsidies to the enhanced subsidies between 200% and 400% of FPL. The state subsidies are not accounted for in the chart above; even with state subsidies, California’s net premiums would not be as attractive as Wyoming. They are roughly comparable to Virginia, a state with a robust competitive market that performs very well due to its prescriptive elimination of Metalball.

Critical Conclusion

Duke University researcher David Anderson says, “There are many ways a state can improve its own individual marketplace. Some are effective at lowering premiums and increasing enrollment and others merely are full of sound and fury and contain no real money flows…We need to differentiate these actions as some states do a bit of both but have rules and cultural/political norms that hobble the markets…We need to separate signal from noise and make trade-offs explicit when we look at what states are doing to their individual health insurance markets.”

He is right. There has a lot of noise and not much substance in state responses to recent ACA regulations. We could argue that ACA dynamics are simply unintended consequences of the misunderstood policy. In my opinion, the problem is much deeper. The overwhelming mistake states have made is they have made decisions based on reflexive political suppositions rather than mathematical understanding and compliance-based policy efficacy. The political consequences of such mistakes are small because the electorate does not understand the policy either, but the market consequences are significant.

The states with the strongest ACA markets have achieved that status from strict compliance with ACA rules and genuine interest in understanding and optimizing ACA dynamics, not from political retaliation. The series of Congressional health care hearings over the last several years have been unfortunate. There has no serious discussion of the overwhelming, improving dynamics in ACA markets; there have been merely name-calling and discussion of sideline issues that are not substantive factors in ACA market development.

The convolutedness of ACA mechanics and the unwillingness to ‘separate politics from policy’ certainly exacerbate the mindless discussions. If President Clinton gets the opportunity to read this, I am certain he will call it “the craziest thing in the world”. President Trump would undoubtedly say “it’s like nothing anybody has ever seen before”. I would humbly describe the current situation as lost sheep getting pounded by Metalball waves in the California surf, hoping to reconnect with their friends on a Wyoming ranch, where maximizing the fruits of finely cultivated land is of greater interest than attacking the new shepherd.

About the Author

Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.