Abstract: A new emphasis on value-based decision making, enhanced understanding of the baseball market, and focus on effective measures enabled the Oakland Athletics to achieve tremendous success despite not having a budget to do so. States can adopt a similar viewpoint and achieve immeasurable success in individual health insurance markets.

I haven’t been to many movies recently, but two that I have seen are Invincible and Moneyball. Observant readers will recognize each as nonfictional portrayals of sports figures with a unique story. A smaller subset will identify the characters portrayed as recent guest speakers at a Society of Actuaries (SOA) business conference. The latter is undoubtedly an inefficient method of promoting a movie, but it has proven effective with me.

Moneyball chronicles the 2002 baseball season of the Oakland Athletics with a focus on general manager Billy Beane’s creative style of developing a roster on a shoestring budget. Invincible tells the gritty story of Vince Papale, “the oldest rookie in the history of the National Football League to play without the benefit of college football experience.” Billy Beane was selected to speak to actuaries because he incorporated an early form of predictive analytics to judge baseball players’ performance. Vince Papale (pictured with me) was selected because he is representative of the Philadelphia (where the meeting was held) spirit and Rocky Balboa was supposedly unavailable. Invincible is inspirational and due similar recognition, but this article analogizes the essential reprioritization of factors in developing and regulating individual market health insurance premiums the same way Moneyball did with building a baseball team.

Moneyball

“Vision is the art of seeing what is invisible to others.”

– Jonathan Swift

Moneyball added fictional liberty to the Michael Lewis book Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game, but the script aligns with reality. Billy Beane achieved success managing a small market professional baseball team with fewer resources than his competitors by utilizing an experimental, value-based style of choosing players. Beane’s character describes the financial challenge as “there are rich teams and there are poor teams; then there’s 50 feet of crap, and then there’s us.”

The movie begins with Oakland falling in the first round of the 2001 American league playoffs, and then losing several high-profile players to larger markets, notably Jason Giambi to New York and Johnny Damon to Boston. Most of the script focuses on Beane’s commitment to achieving success with his new philosophy without the support of the local media or the baseball traditionalists on his staff.

Retooling the roster to be competitive is Beane’s primary challenge, particularly with the dramatic budget distinctions, less than one-third of the New York Yankees to be specific. He recognizes that he has to do something different to effectively compete. That “something” turns out to be making decisions based on evolving sports analytics, rather than doing the same things that other teams are doing and the same things that have always been done.

The catalyst for his experiment is a meeting in another team’s office to negotiate player trades. During discussion as a list of players is deliberated, Beane notices eye contact between the other team’s staff and correctly infers that some of the general manager’s decisions are influenced by whispers from a low-level staff member to an assistant coach, who in turn relays cryptic signals about each player. Intrigued, Beane later privately corners the staff member to inquire about who he is and why he is so trusted. Beane learns his name is Peter Brand, and he is a Yale graduate with an economics degree who just began his first job and has no experience with baseball.

Brand’s role is player analysis, and he relies on complex number crunching and statistical correlation rather than physical aesthetics to inform his opinions of players. He believes that everyone else in baseball, even those incorporating objective statistics, incorrectly values players by using the wrong measures. For example, “batting average” has always been the most prominent statistic, and it’s displayed on scoreboards along with “home runs” and “runs batted in (RBIs)” when players are up to bat. While less flashy, statistical results demonstrate that “on-base percentage” is a more significant performance indicator. Brand shares his thinking with Beane, “There is an epidemic failure within the game to understand what’s really happening. And it leads people who run major league teams to misjudge their players and mismanage their teams. They’re still asking the wrong questions. People who run baseball teams still think in terms of buying players. The goal shouldn’t be to buy players, what you want to buy is wins. To buy wins, you buy runs.”

Perhaps more than any sport, baseball performance can be directly quantified from individual statistics. A running back relies on an offensive line to help his statistical performance; a batter striking out has only himself (and perhaps the umpire) to blame. What if the sport that has the most utility for statistics isn’t properly utilizing them? On the flight home, Beane stares blankly and appears to be processing a lot of information; nothing is said, but he is rethinking his lifelong approach to baseball.

Flashbacks to Beane’s youth reveal a reason for him to doubt conventional baseball thinking. Drafted directly out of high school, Beane was a prototype athlete who excelled in three sports and had a “baseball body and a beautiful swing”. His Charles Atlas physique “lured half the country’s baseball and football scouts to his parents’ house”. He was a “five-tool guy, while most players have one or two and you’re looking to develop an extra one”.

When he was drafted, he had to make a choice between a full athletic scholarship to Stanford and a financially attractive contract to play professional baseball. The movie portrays his parents as preferential to the college route after learning that he could not elect both, but they leave the weighty consideration totally up to their 18-year-old son, who appears frightened and overwhelmed by the gravity of the decision.

Beane was almost the #1 pick in 1980; the New York Mets selected Darryl Strawberry and were able to draft Beane with a later 1st round selection. He never lived up to the sky-high expectations, but nobody faulted the Mets’ selection, except maybe Beane himself in retrospect. “There’s not an organization that wouldn’t have taken a chance on this young guy. He didn’t pan out…it happens every year”, a radio announcer says in the background.

Throughout the film, Beane’s internal emotions appear to transition from disappointment with his own athletic underperformance to anger that maybe his life was cheated by a scouting system that overvalued him. After the 2002 season and near the end of the film, Beane receives an offer from the Boston Red Sox that would have made him the “highest-paid general manager in the history of sports.” He declines and replies, “I made one decision in my life based on money and I swore I’d never do it again.”

When Beane arrives home, his mind is still racing and he makes a midnight phone call. Interested in how he would have personally been evaluated using new statistical techniques rather than his good looks, and perhaps also an anecdotal test of the efficacy of Brand’s methods, Beane startles the young staffer from sleep. “Would you have drafted me in the first round?”, Beane asks three times. Brand complements Beane’s athleticism and tries to dodge the question but ultimately responds with candor, “I’d have drafted you in the ninth round. No signing bonus. You’d have passed and gone to Stanford.” Beane then tells Brand to pack his bags and that he’ll soon be starting a new job in Oakland. Beane wants to find real value in players that is invisible to others, and he needs Brand’s help.

Breaking the Mold

“High functioning people can live under the spell of an inexplicable mental lapse when they think as a group. Why isn’t anybody else doing it? Because they don’t think guys who look like you are what win baseball games. They know it for sure.”

– Peter Brand

The selection of actors to play Billy Beane (Brad Pitt) and Peter Brand (Jonah Hill) is calculated and intended to illustrate different perspectives and upbringings. One is the alpha male athlete and the other is the geeky statistician. The unusual aspect from a social perspective is Beane’s admiration for Brand and trust of his insights. Beane’s subordinates are “baseball people” like Beane himself, and they all think he has lost his mind and are unenthused that a guy like Peter Brand has been invited into their world.

The repeated conversation in scouting meetings involves the team of traditionalists listing players with liked-minded language and comical (serious in their mind) appearance-based attributes, e.g. “good jaw”. Beane dismisses most of their suggestions. They are incredulous with Beane’s attractions to unknown and undesirable players. When asked “Why do you like him?”, Beane always looks or points toward Brand, who sheepishly repeats the same answer for almost every player, “He gets on base”.

Some statistics determine attention. Others determine wins. That is the message of Moneyball.

Some statistics determine attention. Others determine wins. That is the message of Moneyball. Attention-based stats drive player salaries. Stats that drive wins and don’t attract attention are undervalued. A team with a lower budget can compete if it can attract and retain undervalued players. In the same way, states willing to spend significant money can attract attention and perhaps improve their Affordable Care Act (ACA) markets. States without excessive budgets can optimize markets by diligently reviewing the metrics that really matter and by understanding the ‘Metalball’ game being played by issuers in their marketplaces.

Despite Beane’s organizational position as general manager, the resistance to change from his staff is difficult to overcome. His head scout leaves the team midseason; technically he is fired, but only after using colorful words on par with “I quit”. The team manager Art Howe believes Beane’s roster decisions are fatalistic and keeps the bench warm with players that are key to Beane’s experiment; this drives Beane crazy and leads to Beane trying to interfere with lineup decisions. Howe selfishly rationalizes his apparent disregard for Beane’s preferences as he projects the season’s outcome, “I’m playing my team in a way I can explain in job interviews this winter”. Beane counters with midseason trades, leaving Howe little choice but to play Beane’s guys. Despite the relentless opposition, Beane believes in doing what is mathematically right and remains committed to what others view as a misguided experiment.

Moneyball Success

“What is happening in Oakland? It defies everything we know about baseball.”

–Moneyball movie trailer

After a slow start, the Oakland Athletics improved midseason and won 20 games in a row, setting a new American League record. Game 20 was the most dramatic, with Oakland taking an early 11-0 lead and Scott Hatteburg, a catcher who was taught to play first base throughout the season, hitting a walk-off home run in the bottom of the ninth inning with the score 11-11. Of course, it’s his first year on the team and his scouting discussion sounded like this…

I want Scott Hatteburg. Who? Yes, he’s got a little damage in his elbow. Some damage? He can’t throw. Let me understand this. At first base you want a guy who’s been cut from half of the minor league teams in the country due to irreparable nerve damage? He can’t hit and he can’t field, but what can he do? He can get on base.

The New York Yankees and Oakland Athletics each finished the 2002 regular season with 103 wins, the most in Major League baseball. Both lost in the first round of the playoffs, tallying equivalent seasons for two teams with the most extreme payrolls in baseball. Other teams took notice of Oakland’s success. Beane declined a lucrative offer to be general manager in Boston, and the Red Sox adopted the Moneyball methods without him. Two years later, Boston won the World Series for the first time since 1918.

Metalball involves ACA marketplace issuers playing an unfair game that is to the detriment of consumers.

While Billy Beane was able to win at an unfair game by playing Moneyball, Metalball involves ACA marketplace issuers playing an unfair game that is to the detriment of consumers. When rules are unenforced, competitor variance from expected compliance is at greater degrees. When rules are equitably and appropriately enforced, everyone wins in ACA individual markets.

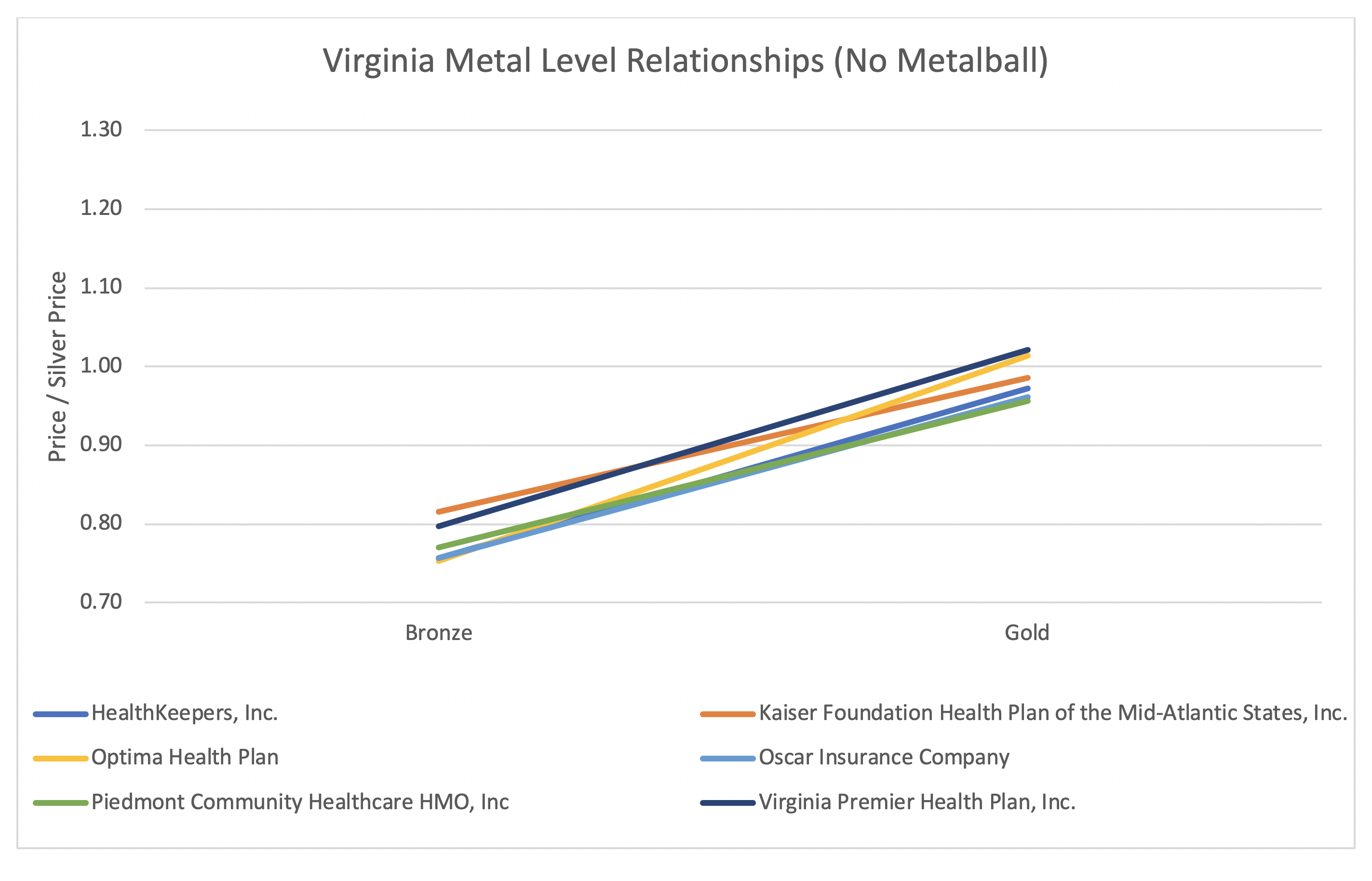

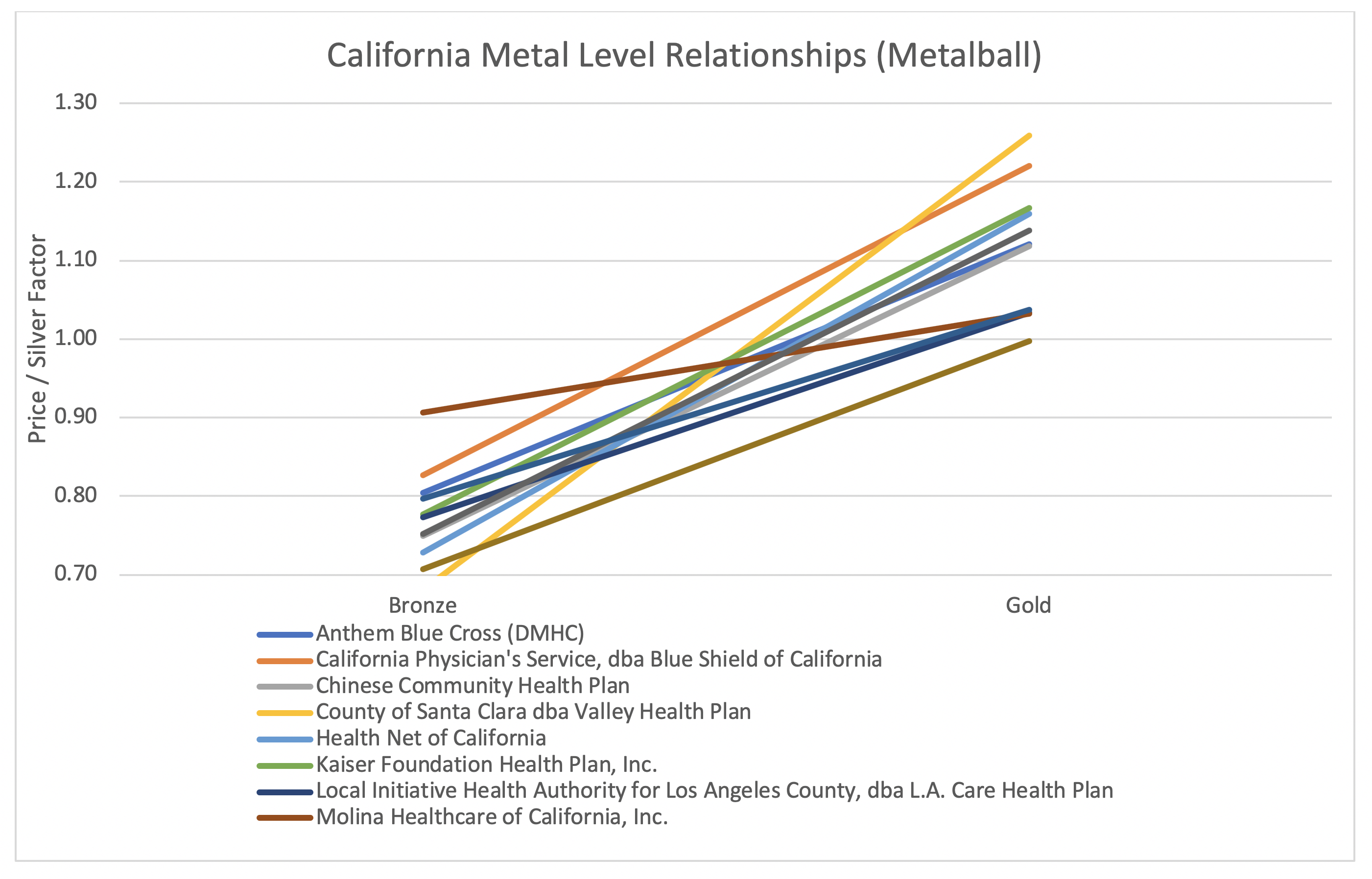

Actual premiums in two states illustrate the Metalball impact. In Virginia, where ‘induced demand’ (usually the bat in the Metalball game) factors are highly regulated, metal level pricing is consistent across issuers. In California, where Metalball is played, it appears that some issuers are strategically competitive at certain metal levels to discriminate between population subsets.

The Metalball impact is not trivial. As subsidized premiums for a benchmark plan are based on a percentage of income rather than underlying health care costs, net premiums should be somewhat similar across the country. My colleague Daniel Cruz notes that “the ACA was designed to force insurance companies to compete on price and quality and not to compete on targeting specific populations. It did so by standardizing benefits and establishing rating rules to eliminate rating games designed to attract certain populations. This should result in carriers having similar metal level slopes.” Nationwide tabulation of nationwide net premiums suggests that is not the case, and Metalball is a popular sport without regional confines. The gamesmanship results in compressed premium subsidies and higher net premiums for subsidized enrollees, as displayed in the charts below.

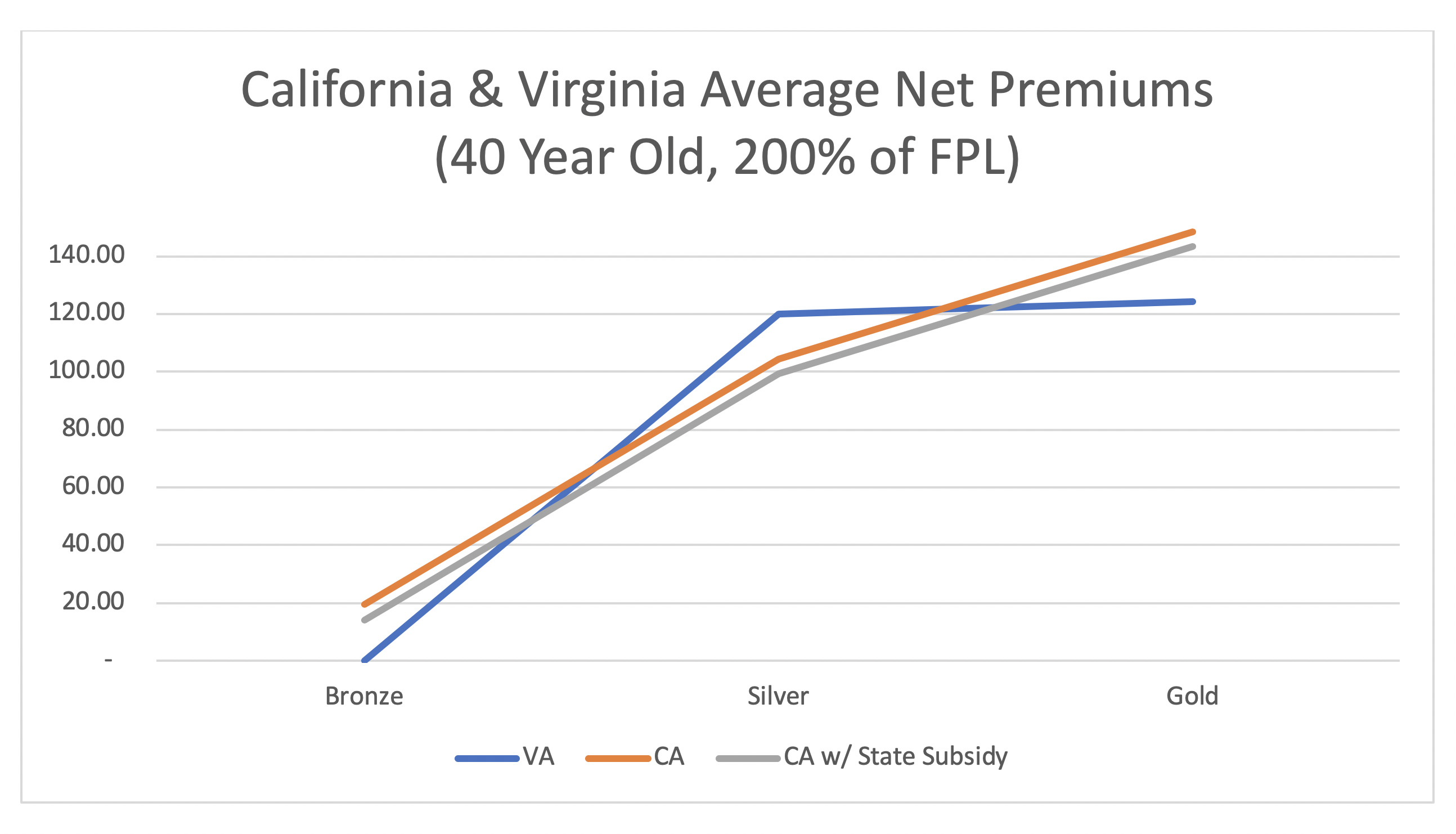

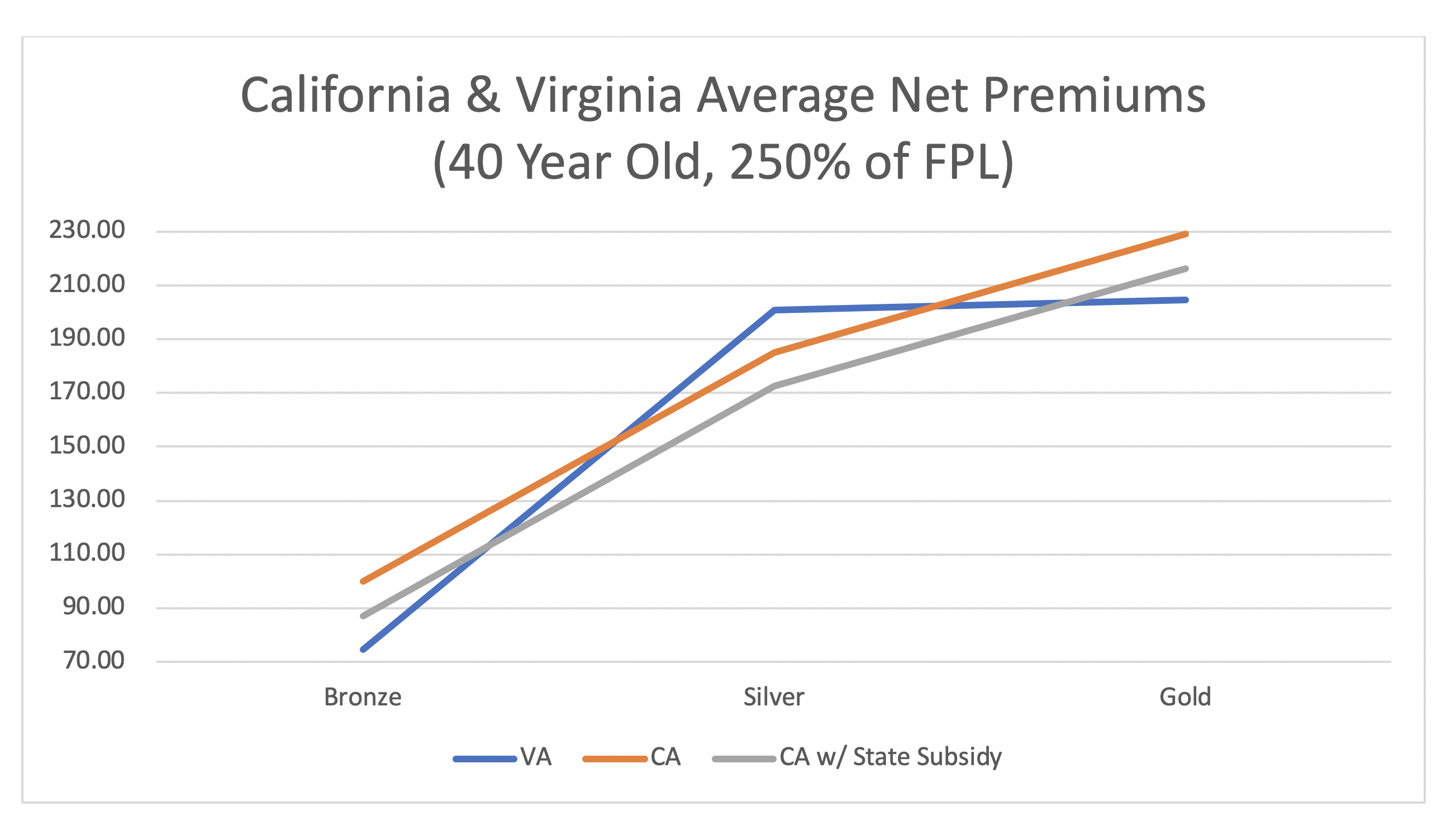

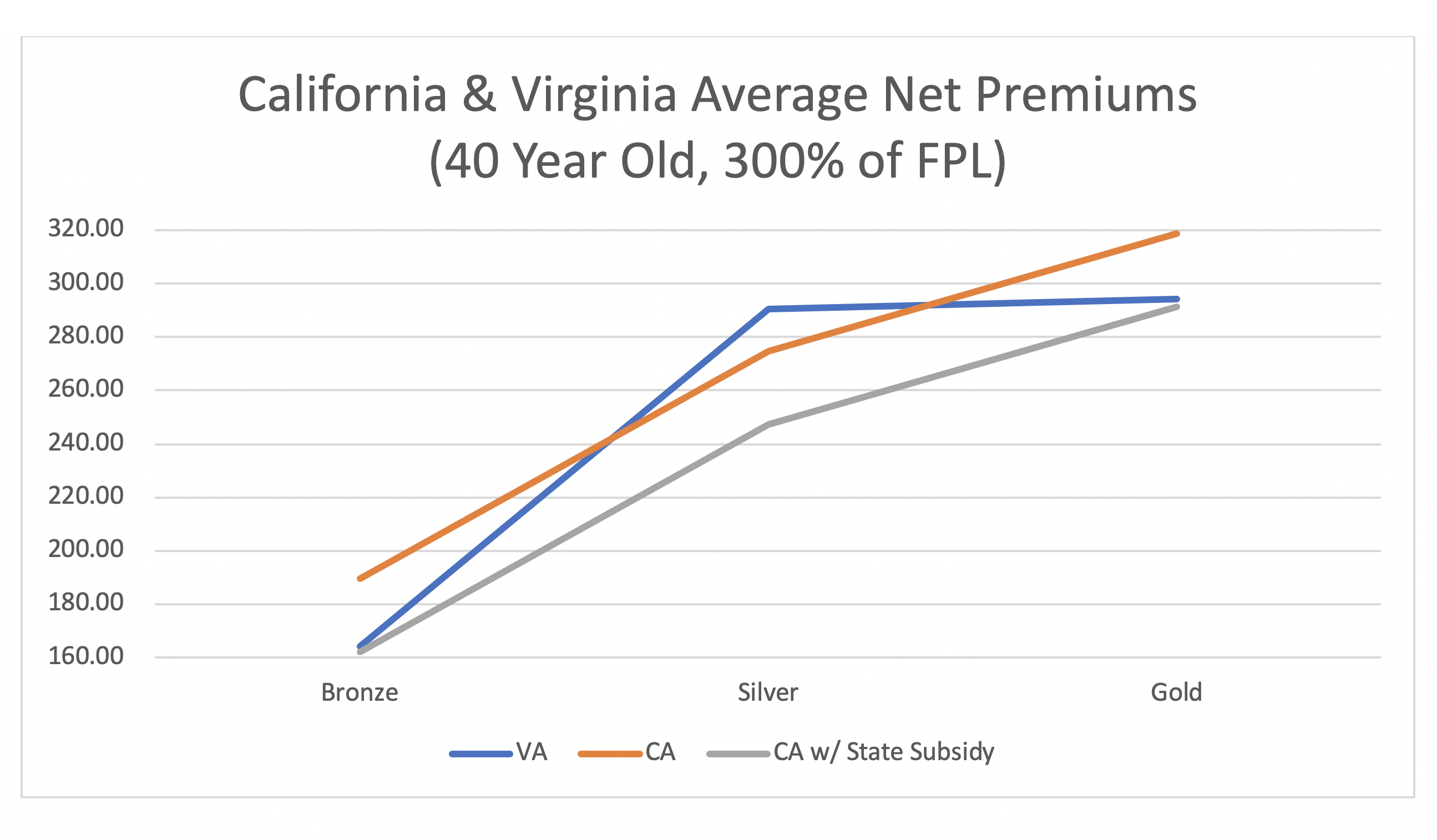

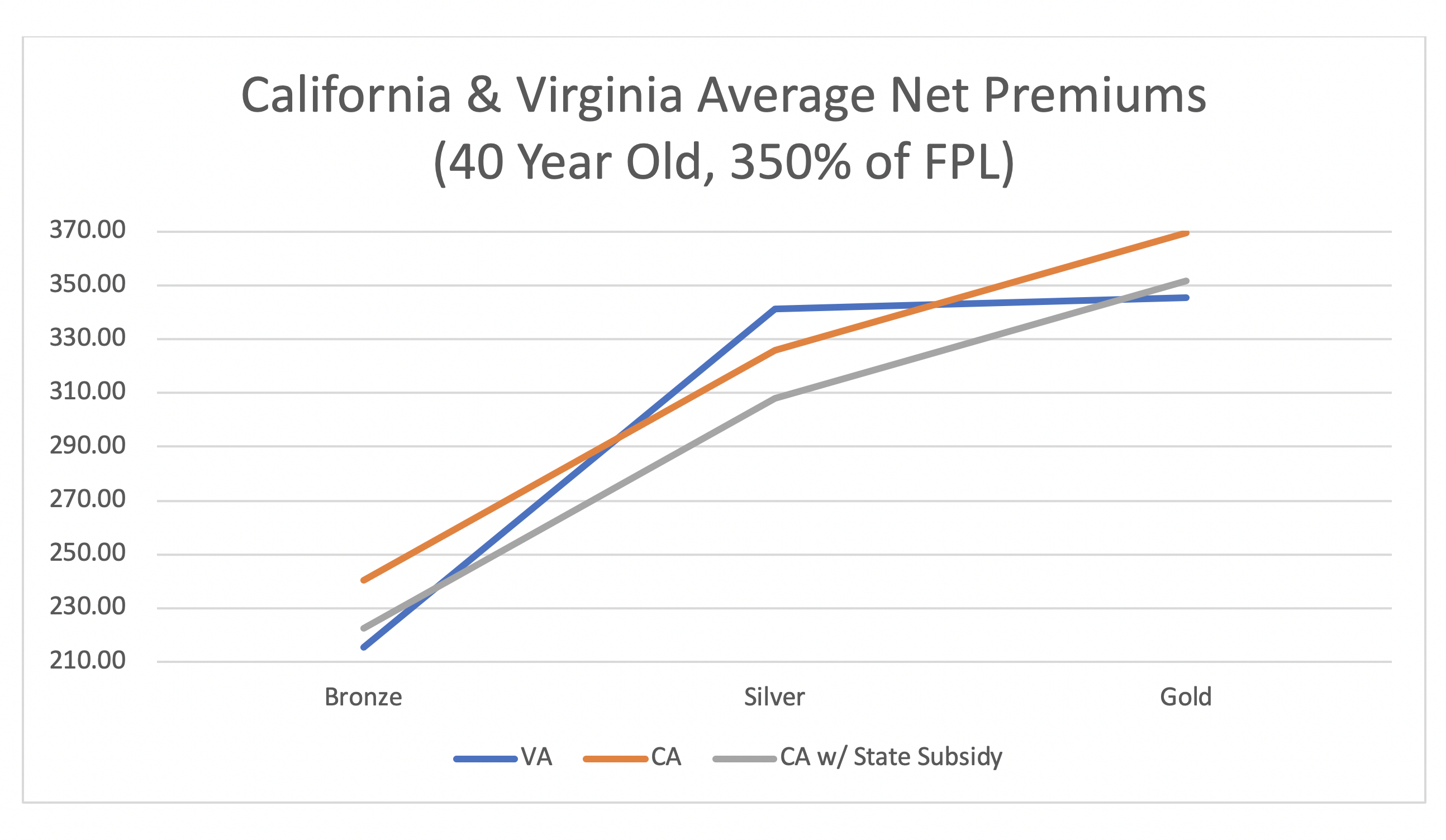

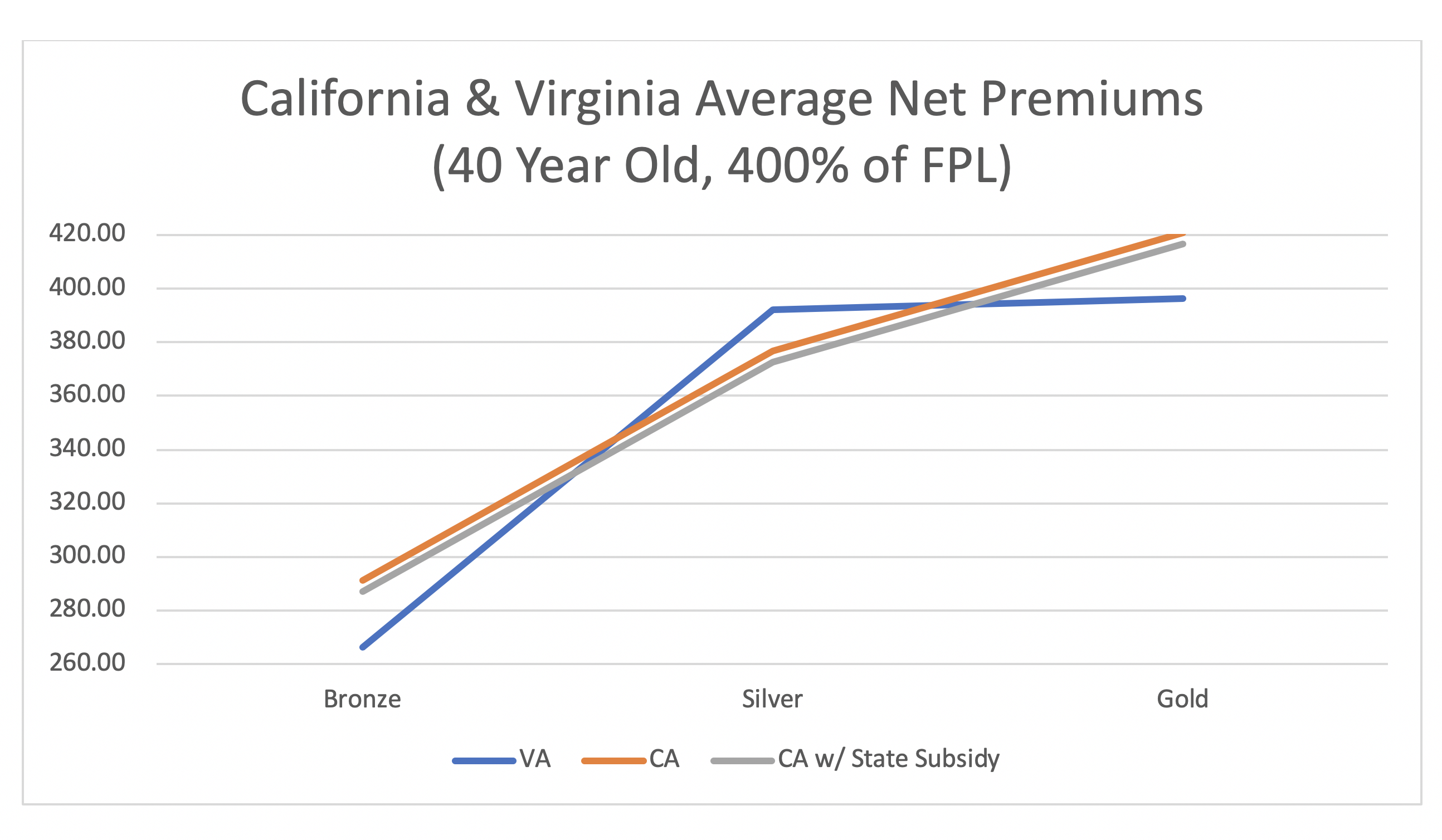

California is an interesting state example as state-based premium subsidies were implemented in 2020 to reduce consumer costs. The income-based charts (as a percent of Federal Poverty Level [FPL]) below illustrate subsidized premiums in Virginia, and in California before and after state-based subsidies are applied.

The state-based subsidies are most generous around 300% of FPL. For this income level, the net premiums for California and Virginia are aligned. It is worth noting that California achieved lower rates by spending state taxpayer money; Virginia has nearly the same effect by simply not allowing Metalball to be played. At other income levels, premiums in Virginia are more attractive than California despite the state-based subsidies.

Notably, California does have lower silver net premiums. This is the result of a standardized benefit package that limits issuers’ silver offerings. The benchmark is reflective of the second lowest cost issuer’s premiums. Virginia allows “silver spamming” and the same issuer often has both the lowest cost silver plan and the benchmark plan, usually at similar prices. This compression results in fewer savings for the lowest-cost silver plan. The state-based California subsidies also benefit a minority of enrollees from 400% to 600% of FPL. In general, California and Virginia have unsubsidized premiums at average levels. Other states have directly reduced unsubsidized premiums through Section 1332 waivers. Eliminating Metalball will have an indirect benefit on unsubsidized enrollees by improving the risk pool morbidity through stronger attraction of healthy lower-income enrollees.

Complicated dynamics have led to Metalball, and states can take action to remedy noncompliance in their marketplaces and effectively promote consumer value at a minimal cost.

Metalball

“Circumstances vary by state and carrier, but these national findings suggest a failure of actuarial soundness, reducing the value consumers receive from individual-market plans.”

–Stan Dorn, J.D., Director of the National Center for Coverage Innovation at Families USA, “Memorandum to State insurance regulators”, July 26, 2019

Traditional insurance regulation has focused on one number, the average annual overall change in premium rates. It’s easy to understand, and historically it has naturally aligned with consumer impact. Rate review has generally focused on the efficacy of assumptions (e.g. medical trend) that impact premium results. Like batting average, homeruns and RBIs, the percentage increase is what appears in local newspapers. Unfortunately, it’s not a real indicator of market success. We all know the historical, longitudinal dynamics; if rate increases are 5% too low this year, they are consequently 5% too high next year; if rate increases are 5% too high this year, they are 5% too low next year to balance. It’s a timing concern and we ultimately end up at the same place. Appropriate alignment of metal level factors has a lasting and reinforcing impact rather than a boomerang effect.

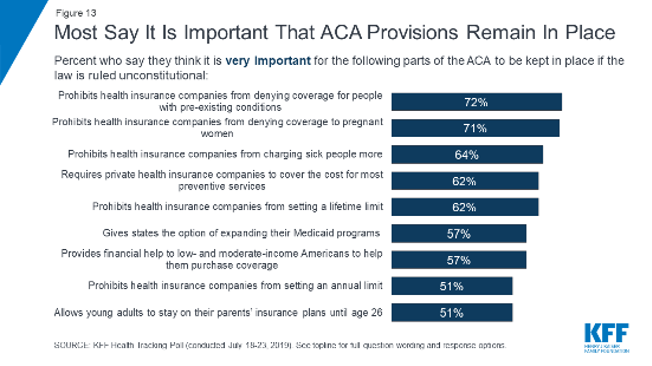

The ACA is better known for its popular anti-discriminatory rules (top 3 in KFF survey) than its extra scrutiny on large rate increases. In keeping with pre-ACA tradition, rate review has been more focused on the latter. Regulators know that discrimination can be inexplicitly applied and more difficult to uncover. Terms such as redlining have been familiar in general insurance discourse for many years. Provider networks can be developed to render products unattractive for people with certain medical conditions, and drugs used to treat AIDS are excluded from some prescription formularies.

The ACA does not allow premium discrimination in the “single risk pool”. The rating instructions state “the Actuarial Value and cost-sharing design of the plan may take into account the benefit differences and utilization differences due to differences in cost-sharing. The utilization difference may reflect the impact higher cost-sharing has on utilization but cannot reflect differences due to health status.” Accordingly, it is expected that benefits offering greater value carry a higher price tag than those offering lesser value as only the benefit plan, not the expected enrolled population, should determine the premium differential. It’s noteworthy that the average silver actuarial value is closer to platinum than gold, 86% in 2018 and 87% in 2019. A survey of national premium rates reveals both a wide disparity in relationships between premiums and benefits, and clear instances where premiums are directionally out of line with value.

At a high level, the ACA was designed to have issuers compete on price and quality, not risk segmentation. As issuers cannot directly charge different prices by gender, health status, or income level, the only risk segmentation avenue (outside of multiple networks) is through strategic metal level pricing, otherwise known as Metalball. As metal level selection should align with income level, Metalball allows issuers to target certain income segments and arrange pricing factors to align with segment profitability rather than benefit value.

Issuers have been playing versions of Metalball since the ACA was implemented, but prevalence increased in 2017 and again in 2018. Metalball initially involved not offering products at certain metal levels or pricing platinum plans unattractively; as experience has developed, it expanded to include comprehensive strategies to review profitability and differentiate premium rates by metal level. From a national perspective, premium relationships were more reasonable through 2016. In 2017, gold premiums spiked relative to silver and the resulting ratio was roughly 10% higher than expected. Beginning in 2018, most states claimed their markets were “Silver Loaded” but a 2019 review found “the overwhelming nationwide evidence is that Silver plans are inexplicably priced more aggressively than other levels, unnecessarily compressing federal subsidies and resulting in higher net premium costs for low-income individuals.”

Could Metalball be flipped and be beneficial to markets? Yes. Consumer value is developed from the prices of plans that consumers buy relative to the plans that determine government subsidies. As subsidies are developed from benchmark silver plans, this means that issuers could play Metalball and increase silver premiums, resulting in higher premium subsidies, lower net premiums, and more attractive value for their products in price-sensitive markets. It would benefit consumers if issuers played Metalball by inflating silver and reducing gold premiums. However, there is no evidence that Metalball has been used to overvalue silver benefits, even in monopoly markets.

Unfortunately for consumers (and ironically for issuers themselves), Metalball is common and almost always results in consumers’ detriment. Silver premiums are reduced, thereby compressing premium subsidies, and offset with higher gold premiums. Subsidized gold consumers pay more in two respects, first as gold premiums are higher and second as premium subsidies are reduced.

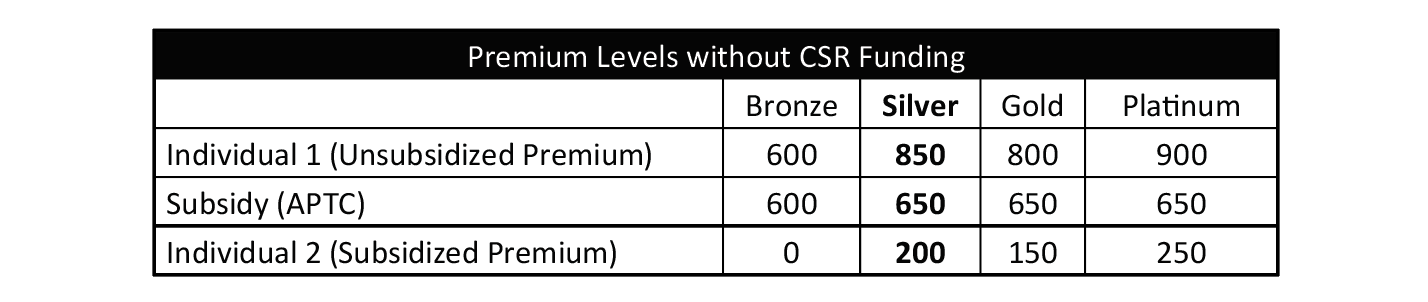

Before Cost-Sharing Reductions (CSR) payments were stricken in October 2017, I illustrated the expected metal level impact of CSR defunding in the summer of 2017. I used round numbers that were simplistic and not intended to be reflective of a specific marketplace. Similar premium relationships are illustrated in an SOA Health Section Strategic Initiative closing article.

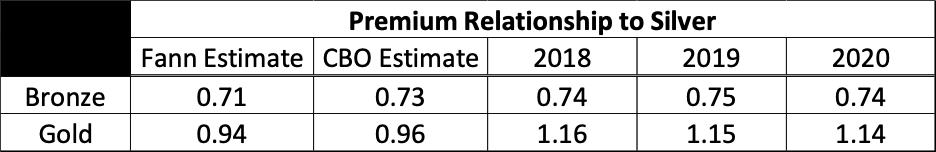

A few weeks later, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released a report with premium relationships that were in line with my estimates. The 2018-2020 federal exchanges results for the lowest cost plan in each metal level indicate that gold/silver relationships are much higher than anticipated.

The CBO expected a gradual increase in silver premiums relative to other plans each year. “After 2018, growth in gross premiums is projected to be slightly slower for bronze than for silver plans mainly because premiums for silver plans are expected to absorb more of the costs for CSRs during the next few years. Such growth for gold plans is projected to be slower than for silver or bronze plans mainly because the fast growth in premiums for silver plans in the marketplaces is expected to cause some people to choose gold plans instead of silver plans and the health of those people is anticipated to reduce the average costs borne by gold plans.” The “gradual” nature is reflective of a steady migration of non-CSR enrollees out of silver plans which are necessarily priced to account for CSR benefits. The pricing relationships have remained largely stagnant from 2018 to 2020 suggesting that the market is not self-correcting toward expected equilibrium.

Why haven’t premiums aligned with expectations? How is Metalball being played to drive gold to silver premium relativities 20% higher than expectations? These are questions I have been diligently researching over the last year. I have learned a lot through conversations and rate filing reviews. Issuers are developing their metal level premiums using different methods and various data sources, resulting in differences that necessarily reflect items other than benefit differences.

The common strategy and unfortunate dynamics begin with the selection of silver plans to hold a dual role in ACA individual markets. Different metal levels could have been selected by ACA framers, but it was decided that silver plans would both determine the premium subsidy calculation and provide all coverage to a large, price-sensitive segment[1] of the marketplace that issuers view as attractive and profitable. The conflicting incentives cannot be overstated here. In one sense, they could offset each other, as issuers have a dual interest in being competitive and consumers’ coverage being heavily subsidized. Almost universally, issuers have leaned toward aggressive silver pricing rather than higher premium subsidies for consumers in ACA markets. It should be clear that regardless of the underlying incentives, the ACA is prescriptive that premium relationships should reflect benefit value and premium compliance does not allow for non-benefit related variances.

While state regulation and news reports may be focused on the average overall increase, some issuers have a different focal point. At the beginning of a motorsports race, the front row vehicle in the inside lane has the “pole position” and the best chance of winning the race. It is a coveted spot usually awarded to the driver with the best qualifying time trial. In competitive markets, many issuers view the lowest-cost silver plan as the “pole position”. The large segment of profitable consumers with incomes below 200% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) are essentially locked into silver coverage due to generous CSR benefits. Price-sensitive low-income consumers are attracted to the lowest-cost plan within a metal tier, so the lowest-priced silver plan attracts many enrollees with incomes less than 200% of FPL. Competition is often fierce. Issuers that cannot justify premiums to occupy the pole position often try to get close; a small change in premiums for a superior product attracts some consumers. Variations of Metalball facilitate hypercompetitive silver premiums and compress premium subsidies.

Various types of issuers participate in the ACA individual market. Without an exhaustive delineation, it’s worth noting one binary distinction. Most issuers operate in other marketplaces, and it’s usually either employer group markets or Medicaid markets. The ACA individual market is a natural addition for both types of issuers. Traditional group insurers offer products and benefits fairly similar to their other markets. Medicaid-focused plans cater to individuals who bounce back and forth from Medicaid and the individual market. Their business model and networks are sometimes not developed for a traditional commercial population. They largely focus on attracting CSR eligible individuals in silver plans, and other premiums fill in the puzzle pieces but don’t attract significant membership. Their focus is understandably on having attractive silver premiums as that is their target market.

In conversations, I have been surprised to hear similar sentiments from traditional issuers that aggressively target CSR enrollees in silver plans. It’s a large market that they believe to be the most profitable. Everything else is window dressing intended to satisfy regulators rather than attract enrollees. This is not the prevailing view, but it is one that exists and is worthy of concern.

This approach clearly sets the stage for a dysfunctional ACA market where silver premiums are aggressively priced, but necessarily overpriced for consumers without CSR benefits. Other metal level benefits are necessarily overpriced to offset silver aggressiveness and coupled with deflated premium subsidies. ACA markets need to provide solutions for all individuals without access to employer-sponsored insurance or government programs, not merely act to serve the population below 200% of FPL. A potential exception exists for states with a tangible non-ACA solution for its unsubsidized population, but all states, at a minimum, need to enforce compliance and ensure that all subsidized consumers are protected in ACA markets.

Conclusion

“Don’t trust your gut on this one, the media, or President Trump. Trust math.”

–The benefits of Trump’s CSR decision, DJ Wilson

The pricing relationship between metal level plans is mathematically wonky, but it is this relationship that is of preeminent importance when determining consumer value. It is also clearly the most abused. This is evident from a specific review of individual issuer Induced Demand factors in rate filings and a nationwide scan of market premium relationships.

Goldwrong measures with consumer value. They may never adopt the right interest in measures that matter, but state commitment to compliance and consumer protection should prevail over aesthetic accolades.

I have been told I can play the Billy Beane role better than most in the actuarial profession, but I’m admittedly more like Peter Brand. My insights arrive not from my charisma, but from complex models I have developed to analyze market premiums and measure market effectiveness. The scenarios are limitless and the calculations are intricate, but a simplistic relationship tells most of the complex story. Markets will strike out with compressed silver premiums, and while it may not have the appearance of a home run, a state that aligns gold premiums below silver in its markets “gets on base”, and umpiring the Metalball game is the most efficient way to dramatically improve local ACA markets for both issuers and consumers.

Endnotes

[1] CSR benefits are only obtainable through silver plans.

About the Author

Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.