“With a one-line regulatory change, Pennsylvania has transformed its ACA marketplace. The measure is probably the most impactful single step a state has taken to improve its marketplace. And the move won’t cost the state a cent.”

– Andrew Sprung, Pennsylvania transforms its ACA marketplace with one sentence

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provides states with multiple opportunities to improve their local markets. Most options involve a significant investment, both staff time and financial resources. Earlier this year, I noted a cost anomaly; “Enforcing ACA rules appropriately aligns metal level pricing, reduces net premiums, attracts a healthier enrollment mix, and ultimately reduces gross premiums in the marketplace. This dramatically improves markets at virtually no cost.”

As I write this, Pennsylvania is the primary news in the United States, not due to the ACA, but vote-counting court battles in the aftermath of the 2020 presidential election. As I write this, we are also near the middle of the federal exchange ACA open enrollment period (11/1-12/15). When the news focus is limited to the ACA, Pennsylvania is also the primary news, as the Commonwealth (if you like trivia, name the other three “Commonwealth” states) along with New Jersey, is migrating to a state-based exchange in 2021.

Pennie and the Jets

The shiny new “Pennie” has received considerable attention. The larger impact on the Pennsylvania marketplace, “the most impactful single step a state has taken to improve its marketplace”, has gone mostly unnoticed; Pennsylvania adopted new regulations in May which require prescriptive “induced demand” factors. In editorial fairness, it’s not hard to understand that Pennsylvania news is littered with articles directing consumers to the new enrollment process rather than informing them that “the induced demand factors on the plans they purchase will be calculated by squaring the Actuarial Value, subtracting the Actuarial Value, and adding 1.24”.

This is all a bit unfortunate because the prescriptive factor change is more impactful. The “Rate Filing Guidance” addresses a flight path that started correctly but quickly went off course, by steering the aircraft toward a final turn to the market equilibrium runway, where lower-income consumers benefit from compliance with community rating rules. Compliance enforcement is strengthened by limiting subjective development of induced demand factors, which unencumbered stray toward Metalball and away from the ACA’s nondiscriminatory tenets.

The National Landscape

Pennie had one analysis drawback. As Pennsylvania moved off the federal exchange, its 2021 landscape results were not included in the annual government report illustrating premium detail in federal exchange states. Even without the strong Pennsylvania results in the annual data, I didn’t hesitate to claim that “2021 will be the best year for the ACA” after reading the report. A significant indicator of market success is state response to President Trump’s ACA makeover, which enhanced federal funding and converted claim payment reimbursements to insurance companies into premium vouchers for lower-income enrollees. The “enhanced federal funding” segment of the makeover is the real construction phase and requires state action, not merely the state acknowledgment that has fooled many ACA observers. States partially responded in the first year of 2018, markets stagnated in 2019 and 2020, and there is a noticeable improvement in 2021.

A quick, simplistic way to understand premium alignment, distance to equilibrium, and market attractiveness is to compare the lowest gold plan to the benchmark plan; my colleague Daniel Cruz has developed a more refined methodology. If a gold plan is cheaper than the benchmark plan, enrollees can purchase a high-value plan for less than an “affordable” rate; the ACA defines affordability as a fixed percentage of income and allows enrollees with incomes below 400% of the Federal Poverty Level to purchase the benchmark plan for an affordable premium. For the purposes of this article, the average lowest cost premiums for each state as calculated by KFF are compared.

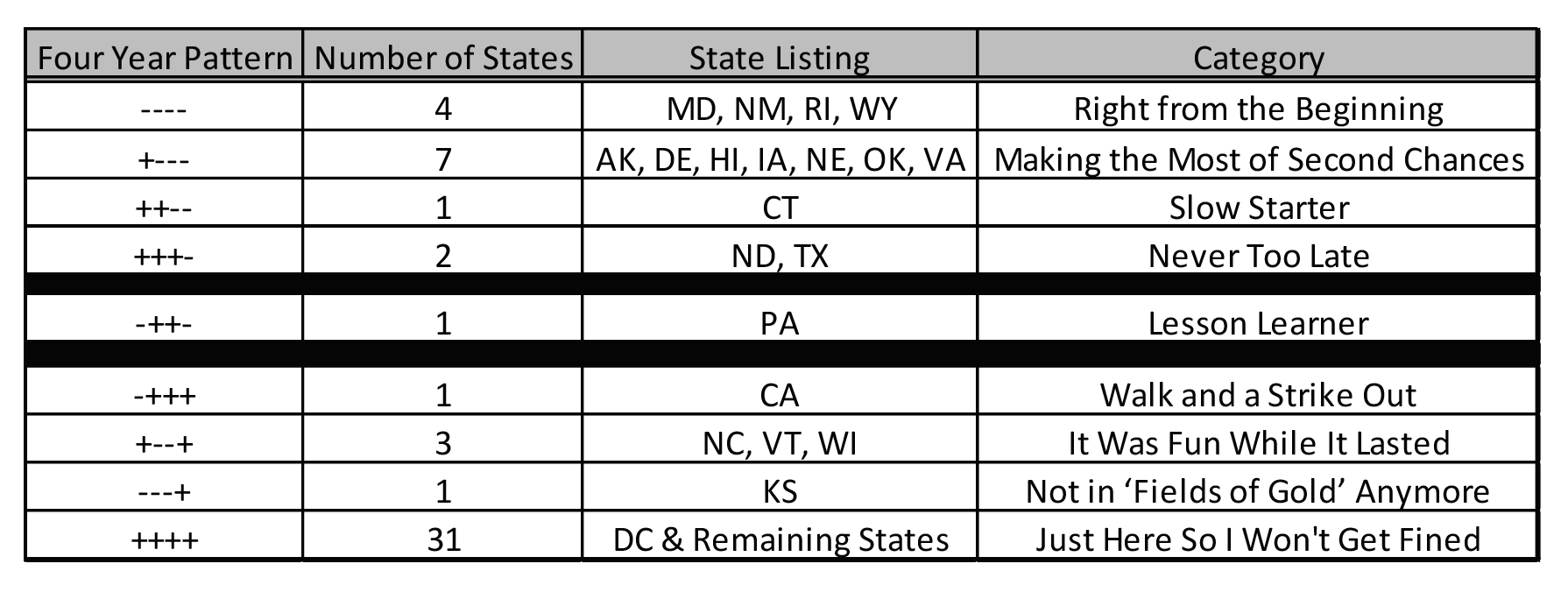

The first column in the table below displays the relationship of the lowest gold premium to the benchmark premium. “-“ simply means that the lowest gold plan is cheaper than the benchmark plan; “+” means it is higher. Relationships for 2018-2021 are displayed as one field. For example, “++–” means that the lowest gold premium in CT was higher than the benchmark plan in 2018 and 2019 but lower in 2020 and 2021.

Four states have succeeded in having lower gold premiums all four years, albeit for different reasons. WY had the fortune of being a monopoly until 2021, and its single issuer could price its products without fear of Metalball competition. The RI state exchange has been active keeping Lionfish out of its market. While the specific beneficial logistics in MD and NM are less direct, active engagement by knowledgeable professionals who understand ACA dynamics have made their markets work.

Seven states took a year to have a gold plan cost less than the benchmark plan and one state took two years. ND and TX moved into the favorable category in 2021; TX is notably one of the three states with over one million enrollees.

PA is the “lesson learner”, having a strong market in 2018, getting crushed in 2019 as benchmark premiums fell 27% while bronze/gold only fell 8%/4%, implementing Focused Rate Review in 2021 and significantly improving local markets.

CA started strong in 2018, primarily due to the Sharp and Kaiser movement toward equilibrium, but those plans regressed to the Metalball market and drifted away from equilibrium in 2019 and 2020. Three states had favorable conditions in 2019 and 2020 but are sandwiched by more challenging years in 2018 and 2021. A drought hit KS after a three-year harvest. Finally, most states have not put forth additional effort to strengthen their marketplaces. They do what they are required to do to avoid trouble, but they have not actively improved market dynamics. Some had planned to take action in 2021 but understandably had their priorities shifted by COVID-19.

Conclusion

The obvious question should be obvious. If it really doesn’t cost anything, it reduces premiums for low-income enrollees, and it benefits insurers, why haven’t more states implemented Focused Rate Review? Why has construction stalled on the ACA makeover? It’s a question I have been asking over the last two years and received a few consistent answers. As health care is the second largest state budget item, even a small portion of the “cost” is often a defensible explanation. That doesn’t apply here; a state needs to hire actuaries that understand ACA dynamics to implement Focused Rate Review, but that’s immaterial relative to the billions of dollars in underfunded premium subsidies. A valid reason is lack of understanding of elusive ACA markets; the media has not been a friend of ACA stakeholders and has neglected discussion of market dynamics for the last three years while relentlessly hypothesizing on improbable legislation, even in relation to reporting on the executive branch. Some states have simply said they believed the ACA was temporal and significant changes weren’t worth the time investment and dealing with disruption. Perhaps the greatest ACA irony is some states have neglected to improve markets through an ACA makeover response due to reflexive posture to federal guidance and their preconditioned “resistance to Trump”.

What is the rationale to not implement Focused Rate Review in 2022? Knowledge? Now you know and you are going to tell your state. Right? President Trump? The election is over. It’s time to end the political pettiness and for states to take appropriate action to benefit their residents. Temporal? Let’s hope not. ACA markets are stronger than ever, they will continue to strengthen, and we need to avoid the federal temptation to meddle with improving markets. Costs? There are no real costs involved in Focused Rate Review. It can be done. It should be done. It has been done. Look at Pennsylvania. They did it. Their market is stronger in 2021. And it didn’t cost a Pennie.

About the Author

Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.