“A subsidy works if it gets someone to buy something they otherwise wouldn’t buy.

Any additional subsidy beyond what is needed to change behavior is wasted.”

– Gabriel McGlamery

I cannot help myself. To celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) last year, I wrote about 30 influential voices in the ACA’s first decade. At the end, I surmised the article probably deserved a reprisal in ten years. But alas, here I am, back after only one and some change. There is so much that happens each year that it didn’t make sense to wait another decade, so I decided to make this an annual update. But 30 voices are too much, so here is the new plan; I am going to list three voices each year and we’ll have another 30 by 2030. There is no fixed agenda for a particular perspective, just my view of who made a significant and unique contribution to the developing future ACA markets. Recommendations are always welcome; just get them to me early in the year before I find the time to write.

I encourage you to take the time and read the original article to understand the background. Following the same model, I have constructed a list of three individuals and entities that have been instrumental in the ACA’s direction this year. Before diving in, I need to share some sad news. Last September, one of the original ACA contributors referenced last year passed away. Henry Stern was an insurance broker and a reliable friend to those who knew him. You can read my tribute to him here.

3 Voices

The Age Equity Champion – The passage of the American Rescue Plan brought long-awaited gains in income equity to ACA individual markets. Age and income inequity have been among the ACA’s primary challenges from the beginning, but there was a reticence to acknowledge either in the ACA’s early years. There were even arguments intended to obfuscate the reality of the ACA’s structural construct. In a Health Watch interview in 2013, Harvard economist David Cutler responded to the reality of young men being disadvantaged and not enrolling in ACA coverage, “I don’t think it will have a huge impact because it will be offset by the subsidies. Many young men have relatively low incomes. Thus, the premium they face will not be the full amount, but rather the amount net of the subsidy. Put another way, the ACA has limits on the share of income that people will pay for health insurance. These limits are sufficiently low that the price will not be a prohibitive factor in determining whether to buy coverage or not.”

Of course, there was some truth that could be found amidst the “lack of transparency”. Some commentators even referenced yours truly. In 2014, Chris Conover wrote in Forbes, “One of the presumably unintended consequences of this misguided law is the fashion in which it encourages some young adults to become uninsured. These are the very young people that the Exchanges need to sign up for coverage if they are to avoid a death spiral…Millennials should be up in arms over how Obamacare is treating them. Greg Fann’s numbers simply help prove my point.” Eventually, admission surfaced that the ACA was prioritized to target certain populations and it wasn’t young men or young adults for that matter. The former administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Andy Slavitt put it this way, “The problem we don’t have is how to help 27-year-olds get cheaper insurance. That’s just not a national concern for us right now.”

While age inequity has never attracted[1] the attention it deserves, income inequity has been a front-page issue for the last several years. “Kill the cliff” has been a rallying cry to allow people who earn over 400% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) to be eligible for federal subsidies, and the American Rescue Plan (ARP) addressed this for everyone where the benchmark premium in their market exceeded 8.5% of their income. Like the ACA itself, this primarily benefitted older people. Young adults are disadvantaged by the ACA, but unsubsidized premium levels do not resonate as astronomical as they are about one-third of the premiums for the oldest adults.

Federal legislation to address age inequity sprung up in the sunshine state in 2020. The bill’s original sponsors were Donna Shalala, a Miami Democrat who served as Secretary of Health and Human Services under President Clinton, and Stephanie Murphy, a third-term Democrat from Orlando. Shalala unexpectedly lost her re-election bid, leaving Murphy to carry the ACA’s age equity legislative torch. A backbench legislator with a moderate reputation, Murphy has been closely watched by health care wonks who realize addressing age inequity would be a game-changer in ACA markets.

As the real brains behind innovative, technical legislation rarely reside in the halls of Congress, the same is true for addressing the ACA’s age inequity. The man behind the mission is Gabriel McGlamery, a Senior Health Policy Consultant in the Government Relations Department at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Florida. The legislation is titled the Health Insurance Marketplace Affordability Act (HIMAA); yes, it is just like HIPAA except with an “M”. Mr. McGlamery had integrated the HIMAA legislation into a subsidy calculator and created impressive visual displays that would impress actuaries. Correction…it has already impressed actuaries. I invited him to speak to present to the Individual/Small Group Subcommittee of the Society of Actuaries Health Section, and his insights were very well received. Mr. McGlamery is kind enough to deflect credit to those who planted seeds and a supporting cast, but this work doesn’t happen without him.

The ACA is structurally flawed. It’s a poorly designed, inefficient financial system. The more inefficient a system is, the more money it needs.

If you read my stuff, you have heard me say many times, “The ACA is structurally flawed. It’s a poorly designed, inefficient financial system. The more inefficient a system is, the more money it needs.” To illustrate this, my air conditioning system can keep my house at 74 degrees, whether my windows are opened or closed; but it costs me more to achieve the same result when they are inefficiently open. It is the same with the ACA; it is like a marketplace with windows always open and requires more money flow, because we have to spend money where it is wasted to spend money where it is needed.

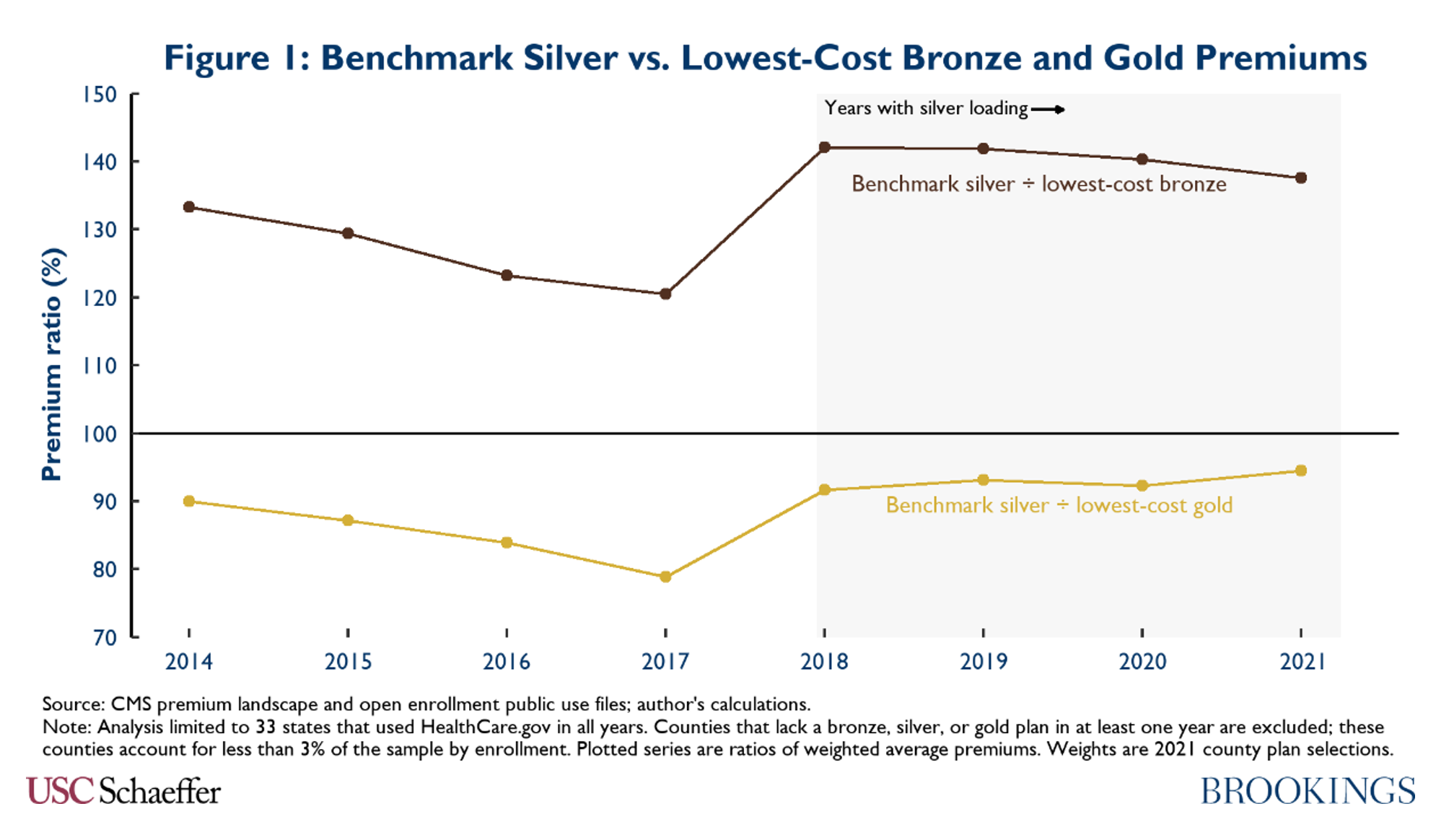

We could cover more people with less money, but the framework was designed like a house with poor insulation; HIMAA would cost money, but it would be more like providing insulation than inefficiently cranking up the air. From 2015 to 2017, consumers began spending relatively less money as silver premiums (which determine subsidy amounts) declined relative to other metal levels. As subsidies are the lifeblood of ACA markets, the law’s two worst years since market implementation were in 2016 and 2017. President Trump’s defunding of Cost-Sharing Reduction (CSR) payments provided a liferaft in 2018 with a major subsidy boost, and the ARP built on that progress.

The CSR action and the ARP both fall in the same inefficient category as the ACA itself. There is a constant push in Congress to keep adding more subsidies, which will likely be inefficient as well. The great thing about HIMAA is that it is designed to be efficient. It considers what the ACA did, who it has helped, and who it is has harmed. It aims to roughly increase subsidies by proportional harm on an age scale. Effectively, it removes most of the age inequity in the ACA dynamics and attracts a broader, younger, and likely healthier marketplace. HIMAA is legislation that Republicans and Democrats should agree on; the debate may very well be Democrats wanting it as an add-on, and Republicans wanting to offset with a reduction in inefficient subsidies, perhaps by letting the ARP-enhanced subsidies expire. HIMAA offers strategic clarity rather than a “series of disjointed changes” or increased subsidies for “those who already have coverage”, and stakeholders advocating for stronger markets and a reduction of the uninsured rate would be wise to recognize HIMAA’s superiority over other ACA modifications.

It would be incomplete to leave this section without mention of the elephant in the room when it comes to premium subsidies. Metal level premiums are misaligned, and the resulting implications are lower silver premiums and higher premiums at other metal levels, compressing premium subsidies. Ironically, this is one area where Mr. McGlamery and I have principled differences. We both support long-term premium alignment, but Mr. McGlamery believes in implementing it through refinement of the risk adjustment methodology – specifically, revisiting pre-ACA assumptions about CSR enrollee utilization, now that CMS can refit these factors with actual enrollee claims data. I am inclined to believe that risk adjustment will always have its challenges and there will always be opportunities for smart actuaries to exploit its weaknesses. I prefer regulatory enforcement, from an anchor point of professionalism, compliance, and consistent treatment. With unenforced rules, insurers are effectively able to create their own metal slopes to align pricing with profitability rather than benefit coverage generosity.

Mr. McGlamery’s market understanding is impressive and he adds candid substance to the regulatory conversation, just as he does to the age inequity concerns. When I speak to the loudest advocates for regulatory premium alignment, they all tell me that their understanding of insurer reticence to accepting premium alignment without corresponding adjustments to the risk adjustment methodology comes from the same source: Gabriel McGlamery.

The Meaningful Lawsuit – The court case on ACA constitutionality ended with a bit of a dud as the US Supreme Court ruled 7-2 that the plaintiffs lacked standing. I had postulated that a ruling on the merits might have surprised people and actually increased coverage rather than dismantling the ACA. It was a case that really bothered me; not because I feared a policy outcome, but because it was the responsibility of Congress to clarify its intent rather than use the case as a fearmongering and election fundraising opportunity. For the record, I did not send Speaker Pelosi a check.

Discernment of Congressional intent should be determined by Congress, not nine justices put in that awkward position. For the record, Congress can and should still address the individual mandate. It has not been ruled constitutional and it’s still dangling from the law, not being enforced, and inviting another lawsuit.

While the world watched and imagined that Obamacare was going to be overturned, I had my mind on a different case; since August 2020. I need to provide the backstory.

The biggest health care policy change in my lifetime (Medicare/Medicaid preceded me) was the Affordable Care Act. The second was the Medicare Modernization Act which introduced pharmacy benefits to Medicare. The third and the most underrated was President Trump’s decision to stop reimbursing insurers for CSR payments, which translated federal funding from direct payments to insurers into additional premium vouchers for enrollees to purchase subsidized coverage.

While it was technically a legal decision, the market necessity of President Trump’s decision is better understood today than it was at the time. The conventional wisdom is that premium subsidies were equally effective from 2014 to 2017 and President Trump gave them a boost in 2018. The reality is easier to see in retrospect; premium subsidies were declining each year and ACA markets were in serious trouble. President Trump’s subsidy boost increased silver premiums, but their relationship to gold and bronze premiums was surprisingly not appreciably different than in 2014. That’s an improved market for sure from 2017, but it is a far cry from the salivating platinum level benchmarks the Obama administration alluded to in 2015.

What in the world is going on here? Premium relationships deteriorated from 2014 to 2017 based on insurers’ actions, ACA markets were in peril, and President Trump righted the ship in 2018, and more insurers returned to ACA markets in each successive year? That’s what the evidence tells us. How did insurers thank President Trump? They sued him.

This case matters. This one should be decided by a court. There are legal issues at play. There are compliance issues at play. There are actuarial issues at play. The deliberations could take us back to the ACA’s original intent, where premium relationships were held tightly together by the ropes of single risk pool requirements and not blown apart by the hurricane winds of disparate profitability.

Actuaries could watch the constitutionality case from a distance. It was an array of legal matters: standing, Congressional intent, essentiality, severability. This case is about actuarial work. If it wasn’t originally, it became so when the court of appeals said, “Go back and recalculate your tax credits as if CSR payments were never defunded….it shouldn’t be hard”. How do you recalculate your tax credits? You must recalculate your premium, and more importantly, the premiums for every other insurer in the marketplace. Do you assume the premium alignment of 2014 or the misalignment of 2017? Is premium misalignment a larger concern in a court case to determine financial relationships where billions of dollars are at stake?

I won’t belabor the point anymore; I wrote about the actuarial implications of the series of CSR lawsuits here; mark my words, there have been a lot of ACA court cases (constitutionality, risk corridors, risk adjustment, exchanges) and we will forget about the details of those. They distracted us but they did not change the ACA’s momentum. This one will. We won’t forget it; it’s a meaningful lawsuit.

The Policy Advisor – Stan Dorn, “The Advocate” of the 30 Voices, continues his good work across the country, including joining me at a Society of Actuaries presentation and on a research report quantifying the subsidy impact of premium misalignment. He has a successful track record, but he is most effective in states with a hungry appetite to strengthen ACA markets. Charles Miller took his first swing at revitalizing ACA markets in…get ready for this…Texas.

Texas is not only a red state that has loudly scoffed at the ACA’s efficacy. Texas is not only one of eleven states that have not expanded Medicaid. Texas has the nation’s highest uninsured rate and it is not even close.

Why is this notable? Texas is not only a red state that has loudly scoffed at the ACA’s efficacy. Texas is not only one of eleven states that have not expanded Medicaid. Texas has the nation’s highest uninsured rate and it is not even close. Texas is the state that led the lawsuit against ACA constitutionality. Texas decided not to help facilitate the ACA construction, and it is one of only three states without an effective rate review process. If there is one state that has a “Just say No to the ACA” reputation, it is Texas. Nobody disputes that. Nobody outside of Texas does, and people in Texas will tell you the same, some ashamedly and others with bountiful pride.

People looking for easy hits on the health policy ballfield take their craft to the parks near the lakes surrounding Minneapolis or the Charles River in Boston, not the Congress Avenue bat bridge above the Colorado River. In fairness, it is not like Mr. Miller was given multiple-choice options. He is based in Austin and works for Texas 2036, an organization that you might have surmised prefers his focus remains between the Red and the Rio Grande. It is incredible what he has accomplished, and we’ll get to that, but first let me tell you how we got there.

Perhaps I’m biased, but Mr. Miller, an attorney by background, deserves credit for not leading with a persuasive argument. Instead, he put an actuarially-informed policy tool on his organization’s website and told state legislators to play with it. They did. And it worked.

The tool educated legislators regarding what policy options were available, how much they would cost the state, the implications on the federal budget, and what it might mean for reducing the uninsured rate in Texas. Some policy options were familiar to legislators who do not operate in ACA circles, like expanding Medicaid or developing a state exchange. Others were more obscure, and perhaps more easily viewed through an objective lens as they lacked any external political baggage.

One option caught the attention of Senator Nathan Johnson, a Democrat from Dallas. It led to the passage of Senate Bill 1296, which received unanimous support. Mr. Miller delivered the sole witness presentation at the applicable Senate hearing. I had accompanied my wife to a business conference in Las Vegas and was able to stream it from a hotel suite. An hour later, I recorded a podcast about new regulatory guidance in Pennsylvania. I remember thinking, perhaps rivaling an October afternoon last year, that it was a really good day for the ACA.

Republican Tom Oliverson led a similar charge in the House. Governor Abbott signed the legislation in June. Effective rate review is back in Texas for the plan year 2023, but it is intended to be stronger than most states. Senator Johnson talked about premium alignment being implemented through Focused Rate Review. It’s not unlike action being taken in other states, most notably neighboring New Mexico, but it’s still among a single-digit number of states taking direct action to enforce ACA rating rules and improve local markets.

Now Texas is part of the mix; Texas quickly went from being the ACA’s biggest villain to one of the leading states improving ACA markets and the action is being implemented to serve Texas residents, not promote the ACA. But Texas is not allowing anti-ACA animosity to cloud the decision to align ACA premiums as politics so often confuse policy decisions nationwide, and people in Texas deserve credit for maintaining a policy focus over tribal politics, and most of that credit should be directed toward Mr. Miller.

The model Mr. Miller’s team developed represents the best state-level policy tool in the country. It led a state legislature to change course on the ACA through logical transparency rather than strong-armed will. Other states should take note. Transparent and objective data can change policy if separated from politics. It happened in Texas. If it can happen in Texas, it can happen anywhere.

Looking Ahead

As the ACA moves into its twelfth year, its markets have benefitted from two subsidy enhancements, the 2018 results of CSR defunding and the 2021 parameter changes in the ARP. Each of the three voices in this article offers further opportunities to improve ACA markets and facilitate better public understanding.

Like the ACA changes in the ARP, Mr. McGlamery’s focus is legislative. The difference is that addressing age inequity is a targeted solution to address an identified problem, not merely throwing more money at an inefficient program to solve a problem that is not well understood. The enhanced ARP subsidies were understandably criticized for providing most funding to people already insured. The intent of premium subsidies is to incent coverage and funds are limited; it’s better spent broadening coverage.

Mr. Miller’s work is also targeted. The policy tool doesn’t prescribe specific policy, but it illustrates the impact to important metrics for each policy option. It will certainly be interesting to see which states follow Texas’ lead and which policies options they construct. As the proportion of ACA enrollees receiving subsidies is now above 90%, improved comprehension of subsidy mechanics will likely better inform policy efficacy. Keep a watchful eye on these three ACA voices as we move into 2022; we have more to learn from them.

We will do this again next year with three new voices. At this juncture, we don’t know who they will be, but if you are speculating that one might work in a city that begins with an “A”, you’re ahead of most readers and…yeah, you’re probably right.

Endnotes

[1] The group “Young Invincibles”, who took their name from a portrayal of young adults being uninsured at higher rates because they believe they are not at risk for unforeseen medical claims, would seem to be the most likely candidate to support age equity efforts. Instead, they champion the nebulous “making sure that our perspective is heard”, seem to be distracted by every fleeting progressive issue, and have always appeared uninterested in addressing generational inequities in ACA markets.

About the Author

Any views or opinions presented in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the company. AHP accepts no liability for the content of this article, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided unless that information is subsequently confirmed in writing.